32 strange places scientists are looking for aliens

From planets and moons in our solar system to dying stars and parallel universes, here are some of the far-out places scientists are searching for alien life.

Are we alone in the universe? If you consider how vast space is, such a possibility seems extremely unlikely. In the Milky Way alone, there are billions of star systems similar to ours, up to half of which could have an Earth-like planet, according to one model.

If life exists outside of Earth, it's been awfully quiet. That's what physicist Enrico Fermi famously pointed out when he blurted out "Where is everybody?" during a discussion of intelligent alien life. But the so-called Fermi paradox hasn’t stopped scientists from scouring space for signs of life — from residues of microbial life to advanced alien technology.

So where have scientists looked for aliens? Here, we explore 32 of the strange places scientists have searched for aliens, or hope to in the future.

Triton

Neptune's largest moon, Triton, is a strange place. Geysers erupt with nitrogen gas, there are organic materials — the building blocks for life — in its atmosphere, and scientists suspect that an ocean of liquid water lurks beneath its icy surface. Windows when Triton is close enough to Earth to launch a mission are limited, and the next opportunity will arise in 2025. In 2020, NASA was considering a mission to this moon as part of its Discovery program, but eventually selected two missions to Venus instead.

Ceres

This tiny dwarf planet, around 1/20 the size of Pluto, is found in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. According to NASA, the planet has two of the most important ingredients for life: organic compounds and water. However, the atmosphere on this planet is thin and it's likely very cold. In 2018 students, with the support of scientists from the European Space Agency, proposed a mission to collect and return samples from this planet. However, no such a mission has yet been greenlit.

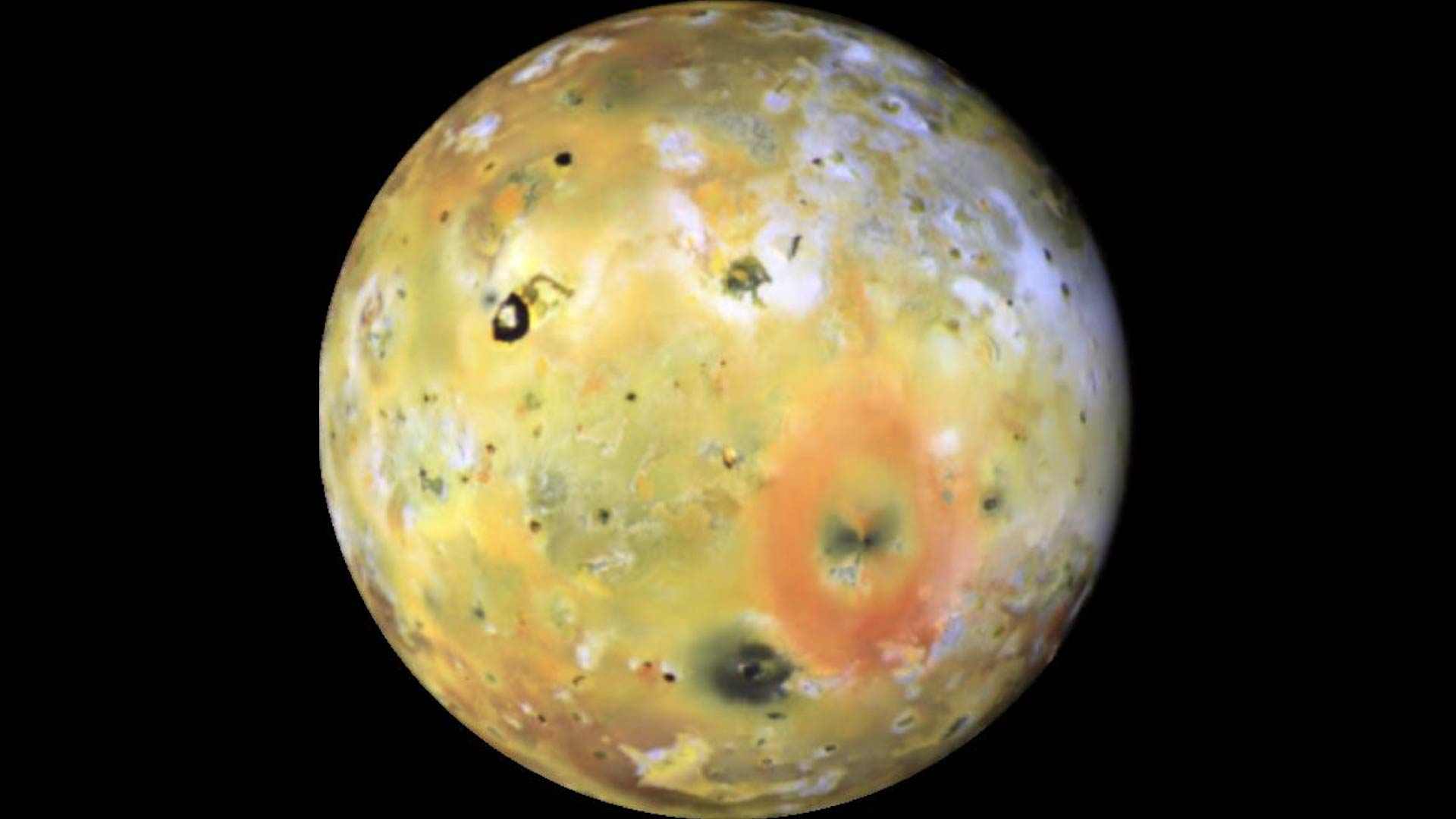

Io

Io, one of Jupiter’s 95 moons, is the most volcanically active body in the solar system. Even though volcanoes erupt with magma, its surface is icy. These harsh conditions, combined with intense radiation from Jupiter, make it an unlikely habitat for life, according to NASA. That said, some scientists argue that water ice, and possibly liquid water, once existed on Io’s surface — and that these materials could still exist underground, where heat from volcanic activity might encourage the formation of life. A mission to Io was proposed for 2029, but NASA passed the idea over in favor of its two upcoming Venus missions.

Related: NASA reveals 'glass-smooth lake of cooling lava' on surface of Jupiter's moon Io

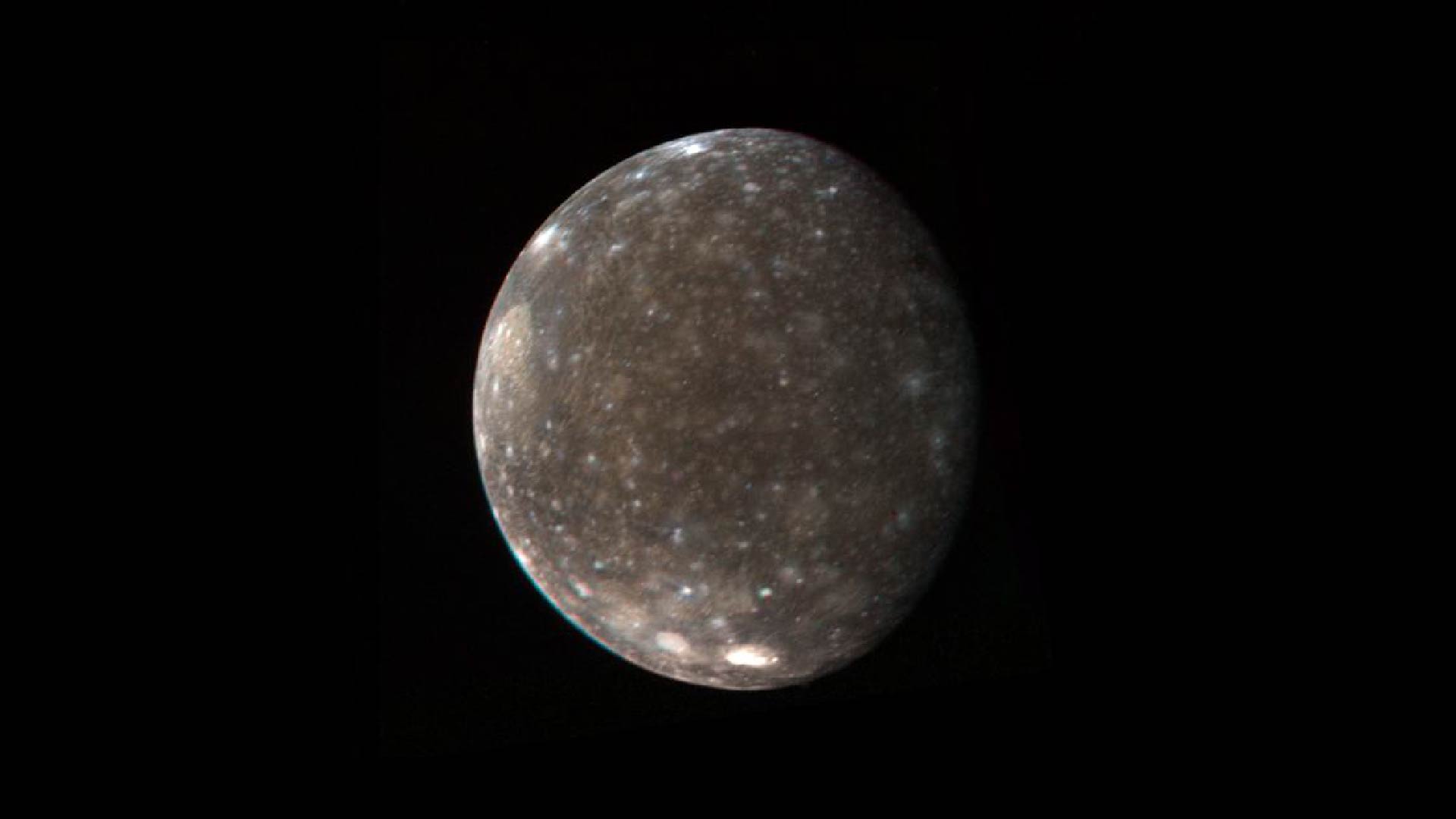

Callisto

The Galileo probe, which orbited Jupiter between 1995 and 2003, was the first mission to catch a glimpse of Callisto, one of Jupiter’s largest moons. Galileo found evidence that oceans of liquid water might exist underneath Callisto’s surface, and that this moon’s thin atmosphere might harbor hydrogen, carbon dioxide and oxygen — all important signs of habitability. The European Space Agency’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE), which launched in 2023 and is set to arrive at Jupiter in December 2031, will make 21 flybys of Callisto and could settle the question of whether Callisto indeed has a subsurface ocean, according to LiveScience sister site Space.com.

Ganymede

On its mission to explore Jupiter’s moons, JUICE will perform 12 flybys of Ganymede, the solar system’s largest moon, according to Space.com. There is some evidence that Ganymede’s icy surface, like Callisto’s, may hide a vast, salty ocean — potentially containing more water than all of Earth’s oceans, lakes and rivers combined. Using cameras, sensors and radar, JUICE will determine whether this ocean exists — and could even detect molecules produced by life.

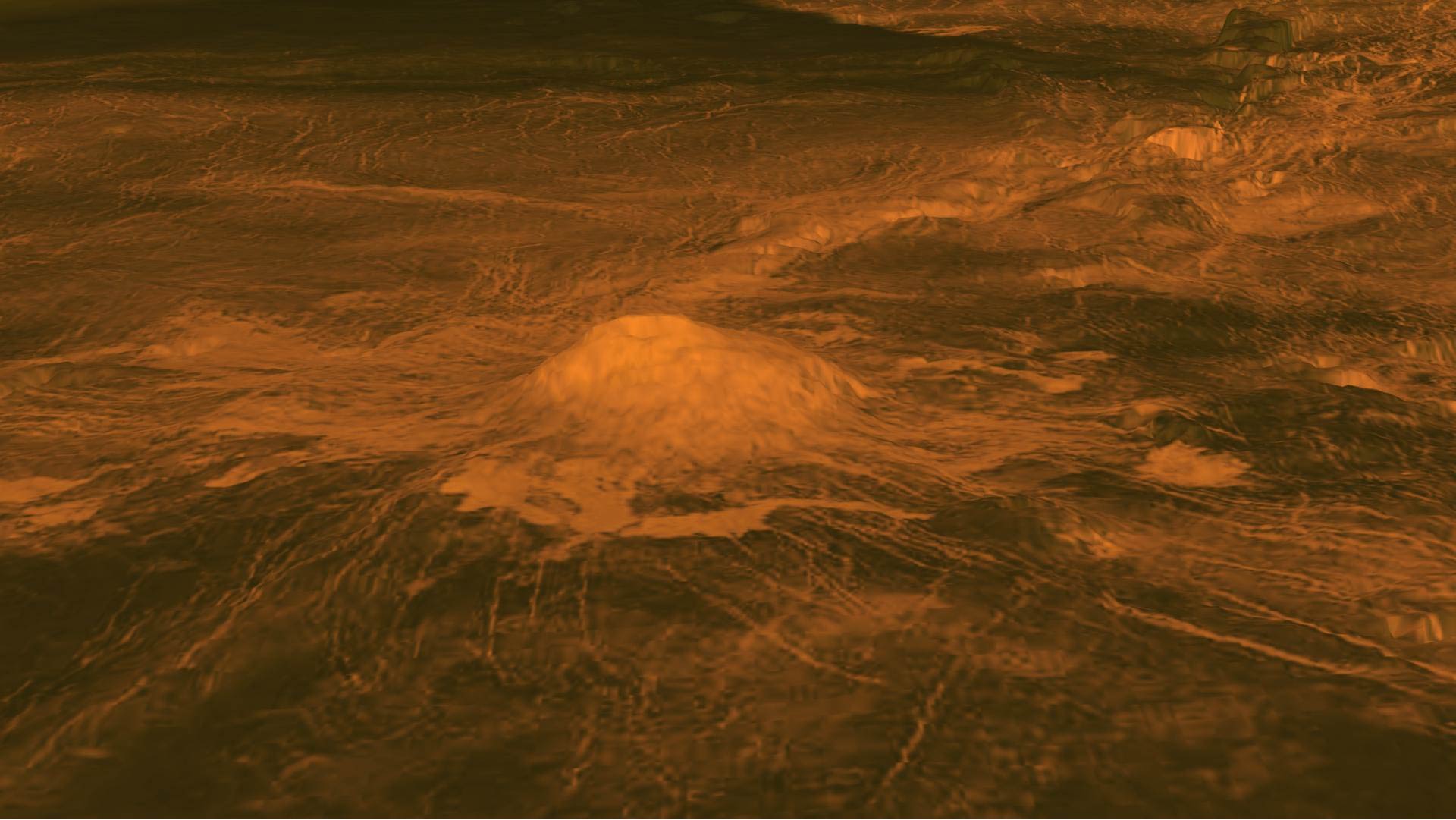

Venus

The second planet from the sun may have once been Earth-like, with a temperate climate and liquid water, according to NASA. Although a runaway greenhouse effect evaporated Venus’s oceans over a billion years ago and high temperatures blast its surface, we can’t rule out the possibility that life still exists there. Any possible remaining life would likely be microbial and airborne — Venus’s atmosphere may also contain phosphine gas, which may be a sign of life. Launching later this decade, the DAVINCI+ and VERITAS missions will take samples of Venus’s atmosphere and map its surface, hopefully answering questions about its past and present habitability.

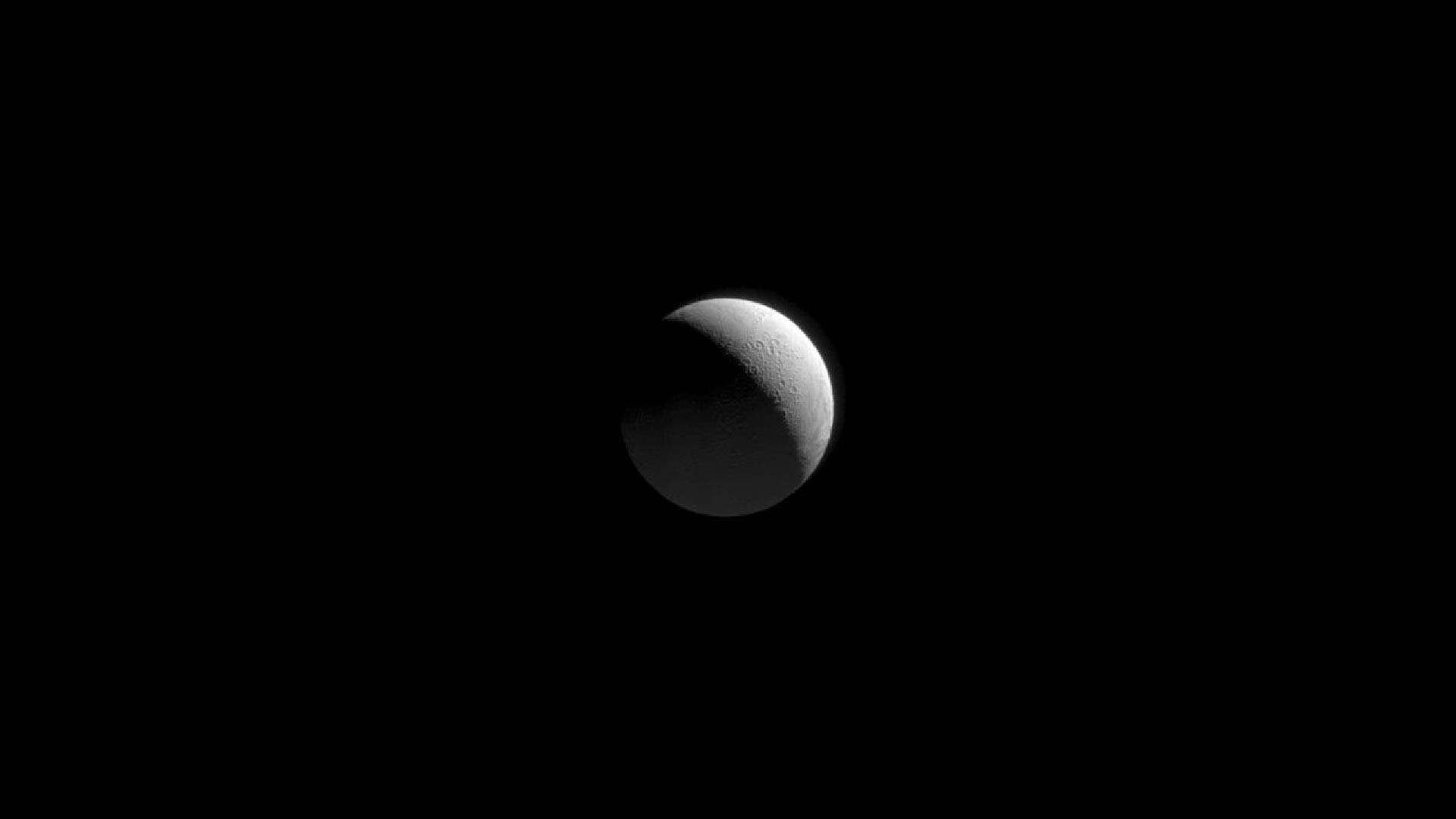

Enceladus

In 2017, on its way to Saturn, the Cassini spacecraft paid a visit to Enceladus, one of the planet’s largest moons. According to Space.com, that mission discovered both liquid water (in the form of subsurface oceans) and organic molecules — both important ingredients for life.

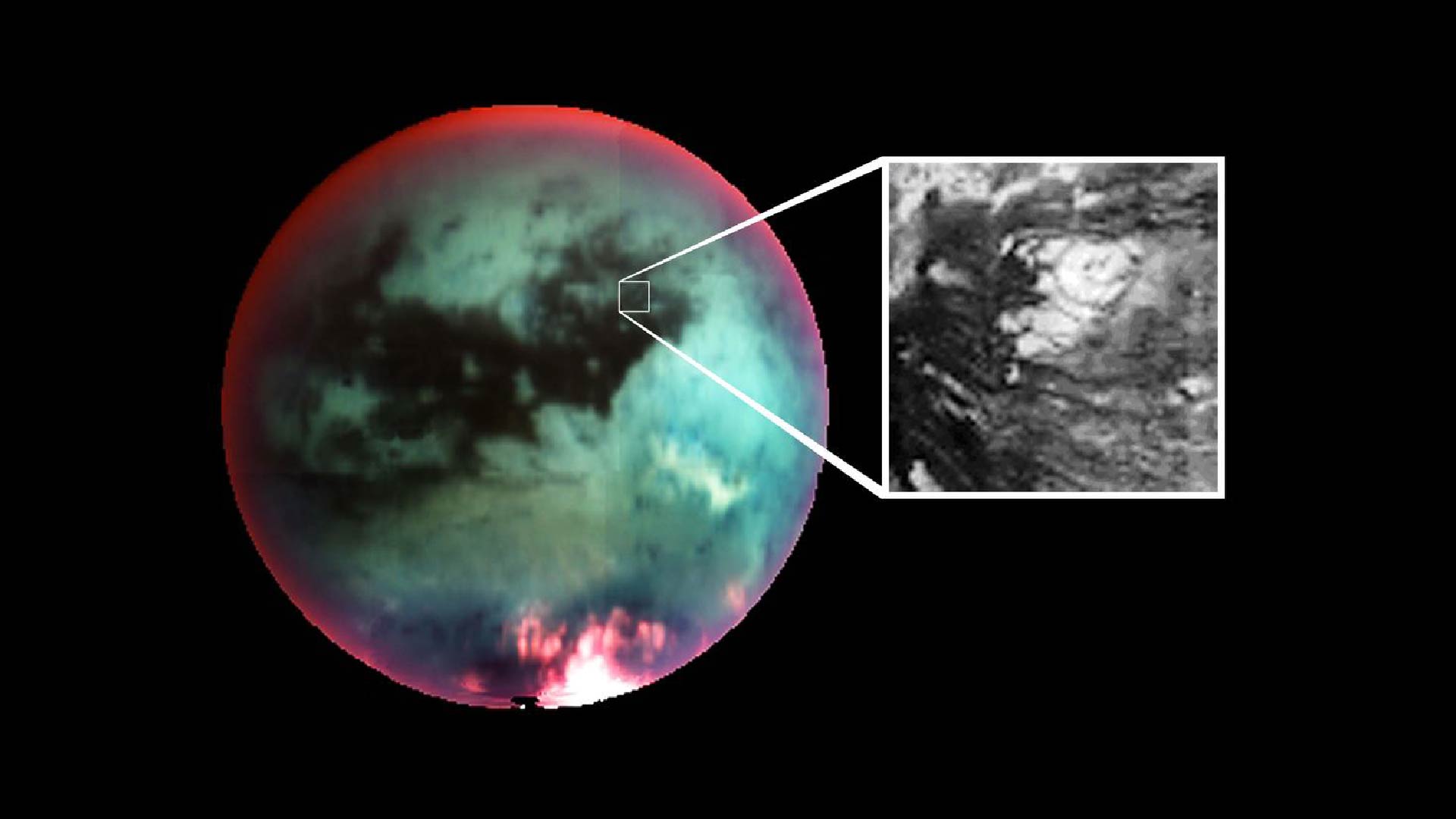

Titan

Saturn’s largest moon is rich in organic materials, and according to NASA, it’s “an analog to early Earth.” Like Earth, it has a nitrogen-based atmosphere, but unlike Earth, methane rain falls from the sky. Launching in 2026, NASA’s Dragonfly mission will land on Titan in 2034 and collect samples from dozens of locations — potentially uncovering more concrete evidence of life.

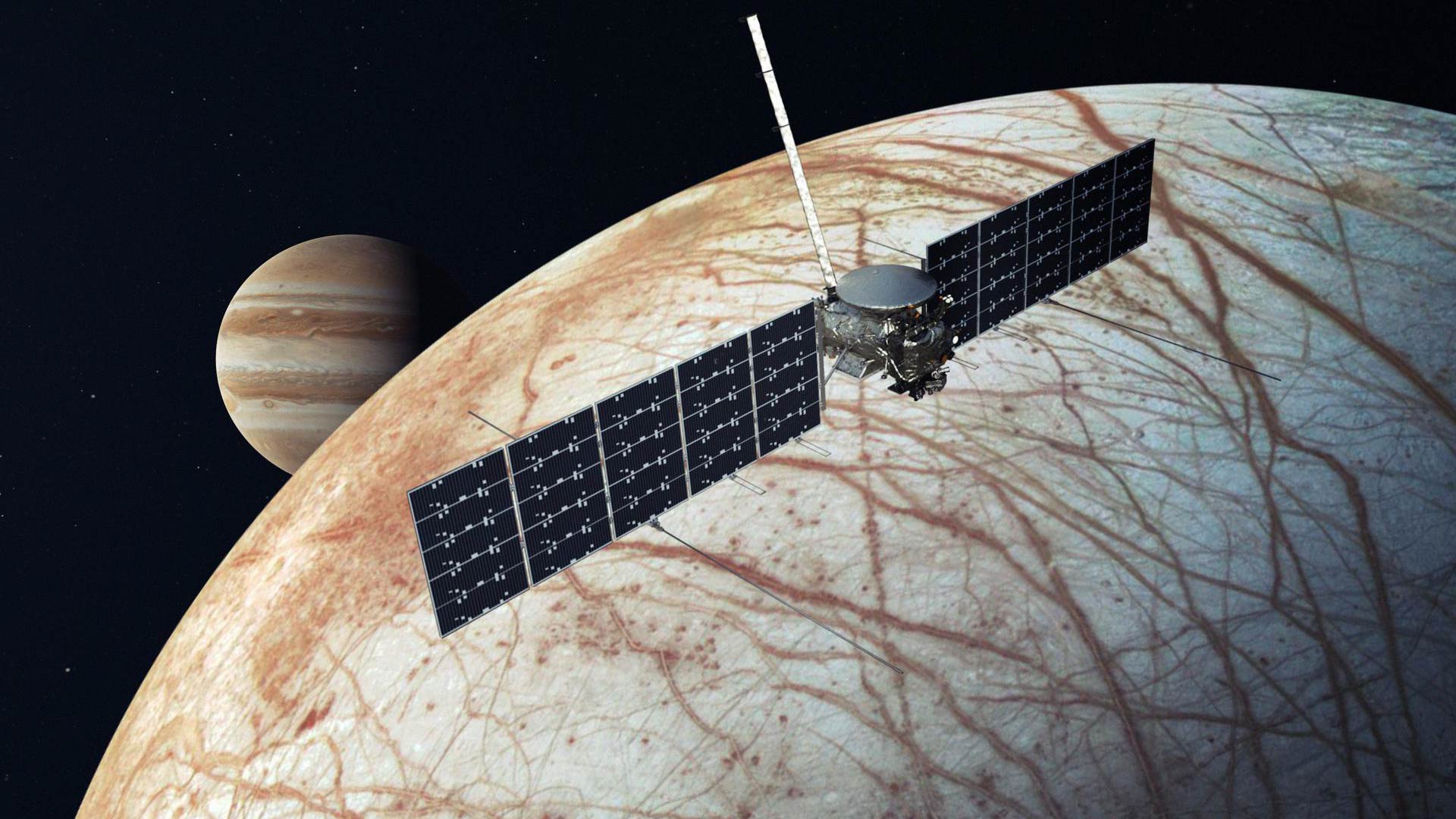

Europa

In the search for life beyond Earth, Europa, the fourth largest of Jupiter’s moons, is “one of the most promising places in our solar system,” according to NASA. A huge saltwater ocean, containing twice as much water as Earth’s, is believed to exist beneath the moon’s surface, and might contain organic material. Scientists believe that ocean currents constantly circulate that water — so microbial life, if it exists, could leave traces in the planet’s icy surface. Launching in 2024, NASA’s Europa Clipper, a solar-powered space probe, will make a low-altitude fly-by to study the planet’s surface and determine if such an ocean exists.

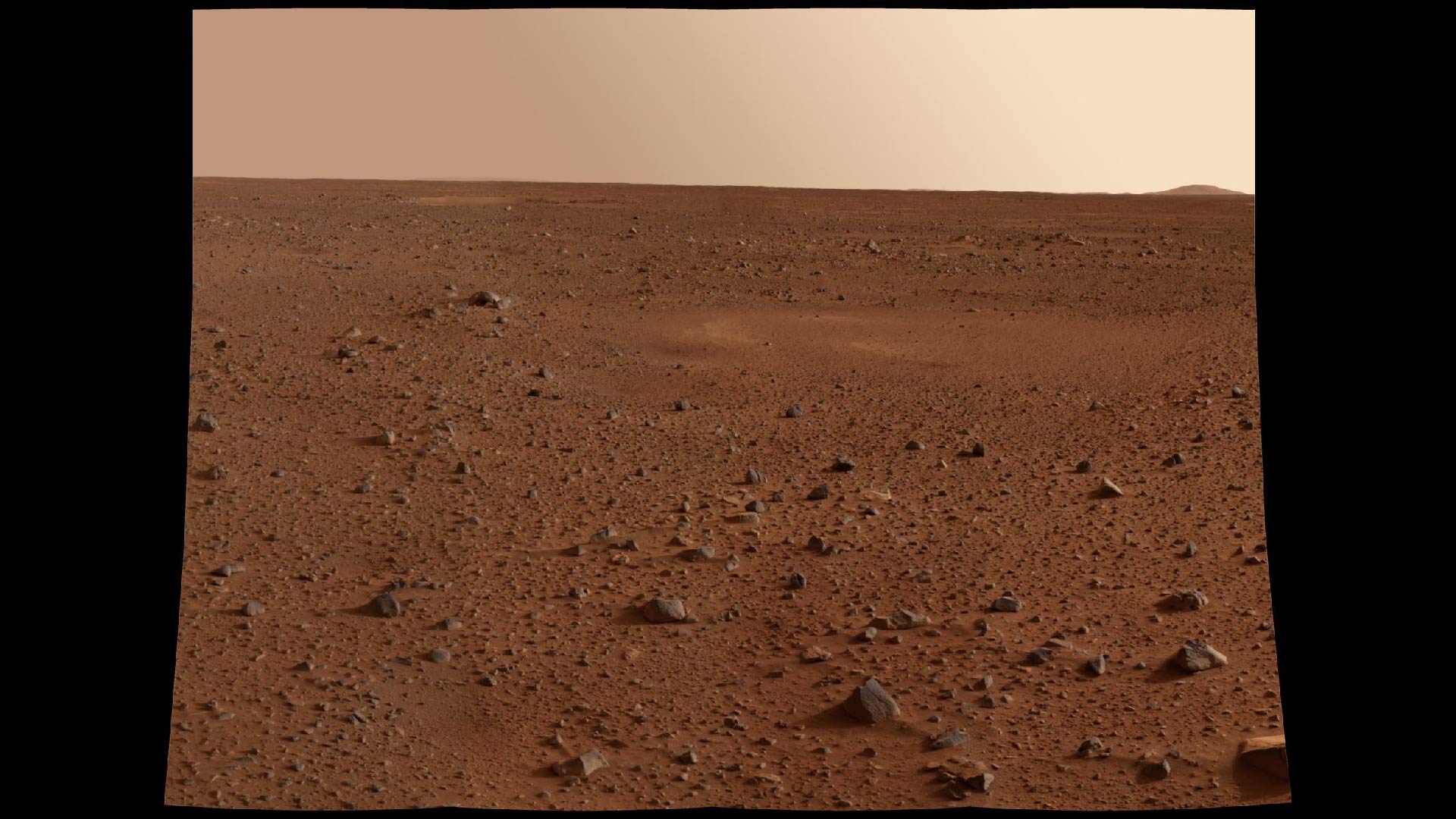

Mars

Mars, like Venus, was once an Earth-like planet, with lakes, rivers and warm climate. It might even still have reservoirs of liquid water a few kilometers beneath the surface. That makes it a strong candidate for remnants of life — likely microbial and below the planet’s surface, if they exist at all. The Mars 2020 Perseverance Rover, one of many missions to Mars, landed in Jezero Crater in 2021, and is analyzing rock samples from the former lakebed and other sites for potential signs of life.

HD 110067

Powerful technology like the James Webb Space Telescope has enabled scientists to search for habitable exoplanets — planets outside of our solar system. HD 110067, a star system hosting six planets smaller than Neptune, is one site of interest for scientists searching for extraterrestrial life. Recently, researchers aimed the Green Bank Telescope at this planetary system to search for technosignatures — radio frequencies indicating the existence of technologically advanced civilizations. Their study, published in the journal Research Notes of the AAS, didn’t find any evidence of life, but the scientists aren’t ruling out the possibility.

Kepler-38

Kepler-38, a planetary system with two stars orbiting one another, is just one of five multi-star systems that scientists identified as promising candidates for life in a 2021 study. Each of these star systems, located between 2,764 and 5,933 light-years away in the constellations Lyra, the harp and Cygnus, the Swan, is likely to contain worlds sitting within its permanent habitable zone — neither too close to nor too far from the parent star for liquid water to exist.

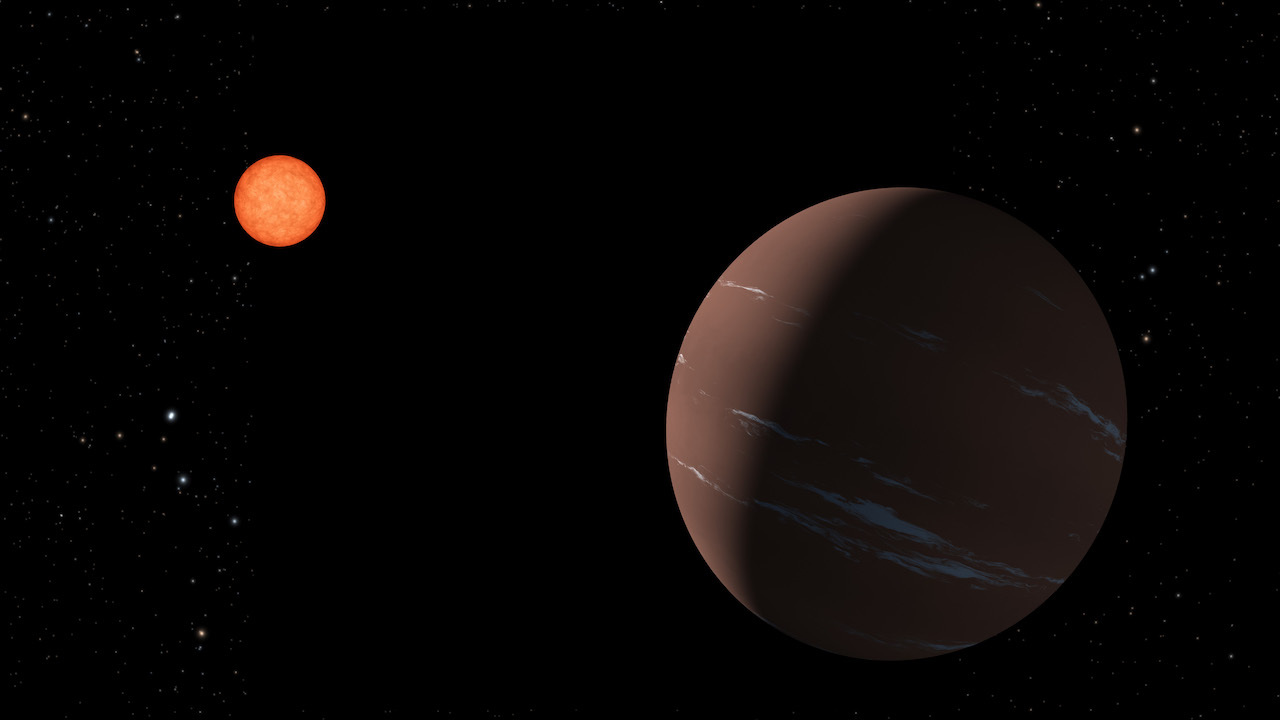

TOI-715b

On TOI-716b, you’d celebrate New Year every 19 days. That’s how frequently his “super Earth” orbits its star, a red dwarf only 137 light-years away. Scientists in the UK discovered this planet in early 2024, identifying the rocky world as a potential candidate for life because it’s right within the habitable or “Goldilocks” zone of its host star.

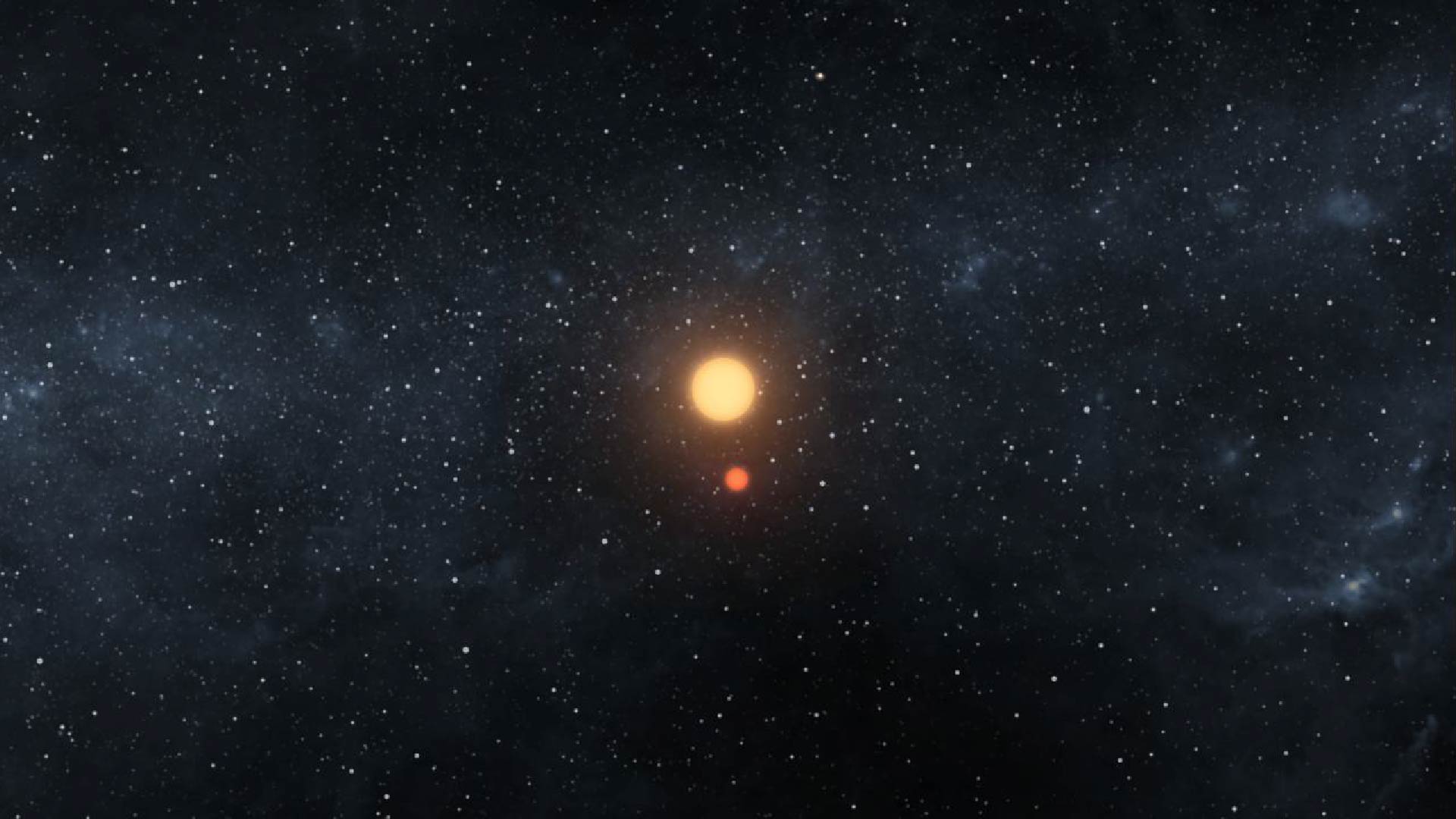

Real-life Tatooine

Imagine watching not one but two suns sink below the horizon in a strange double sunset, just like the fictional planet Tatooine depicted in “Star Wars”. That would be possible on planets like Kepler-16b. This exoplanet has a “circumbinary” orbit, meaning it circles two stars. While Kepler-16b exists outside its star system’s habitable zone and is likely too cool for life, scientists have suggested that up to 60% of binary star systems could form planets with the necessary conditions to support life.

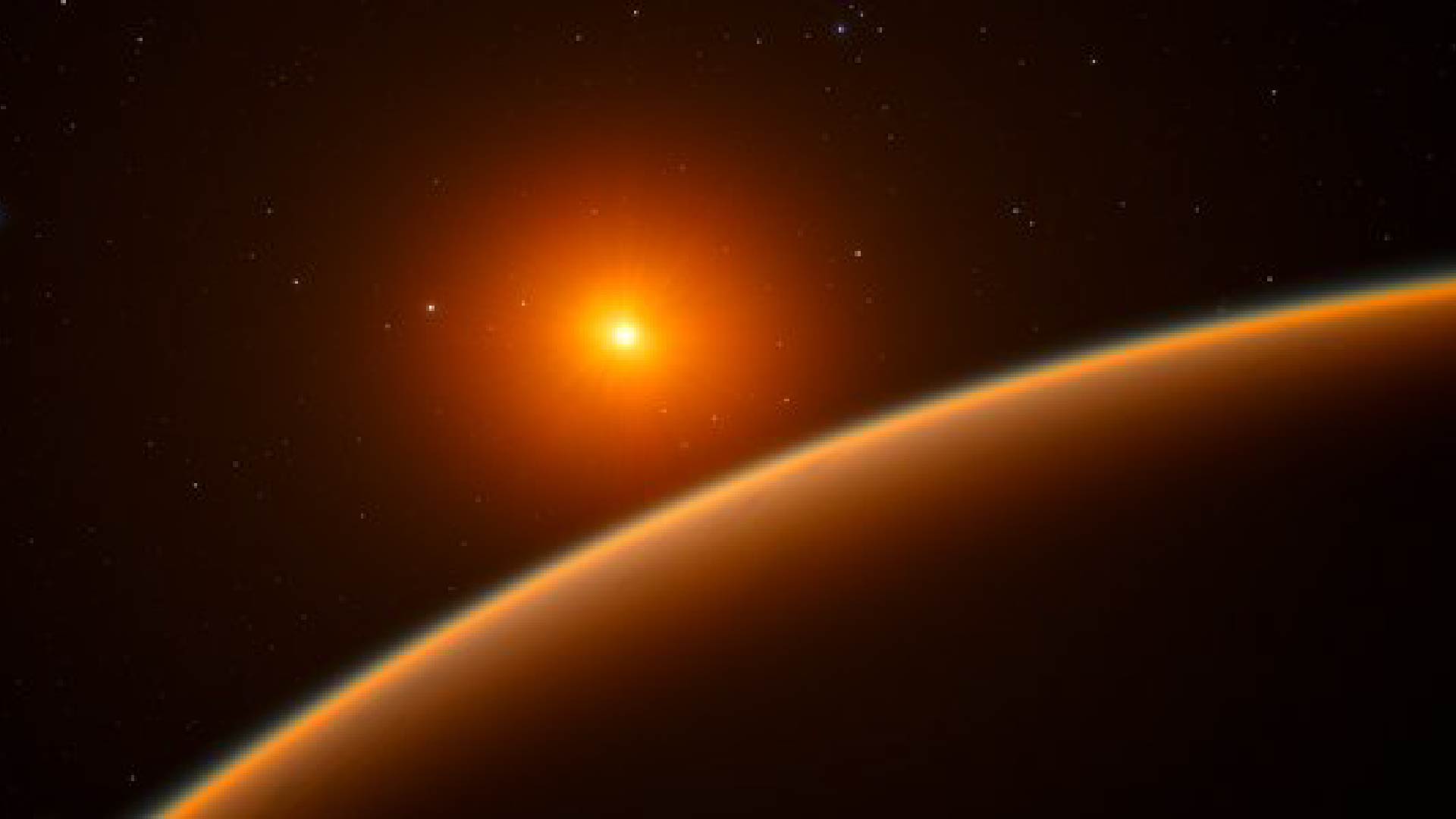

TRAPPIST-1

Recently, the James Webb Space Telescope turned its mirrors towards a far-away star orbited by seven Earth-sized worlds, Space.com reported. Located 39 light years away, the star system is visible in the Aquarius constellation. Most promising is the fourth planet from the star, dubbed TRAPPIST-1e.

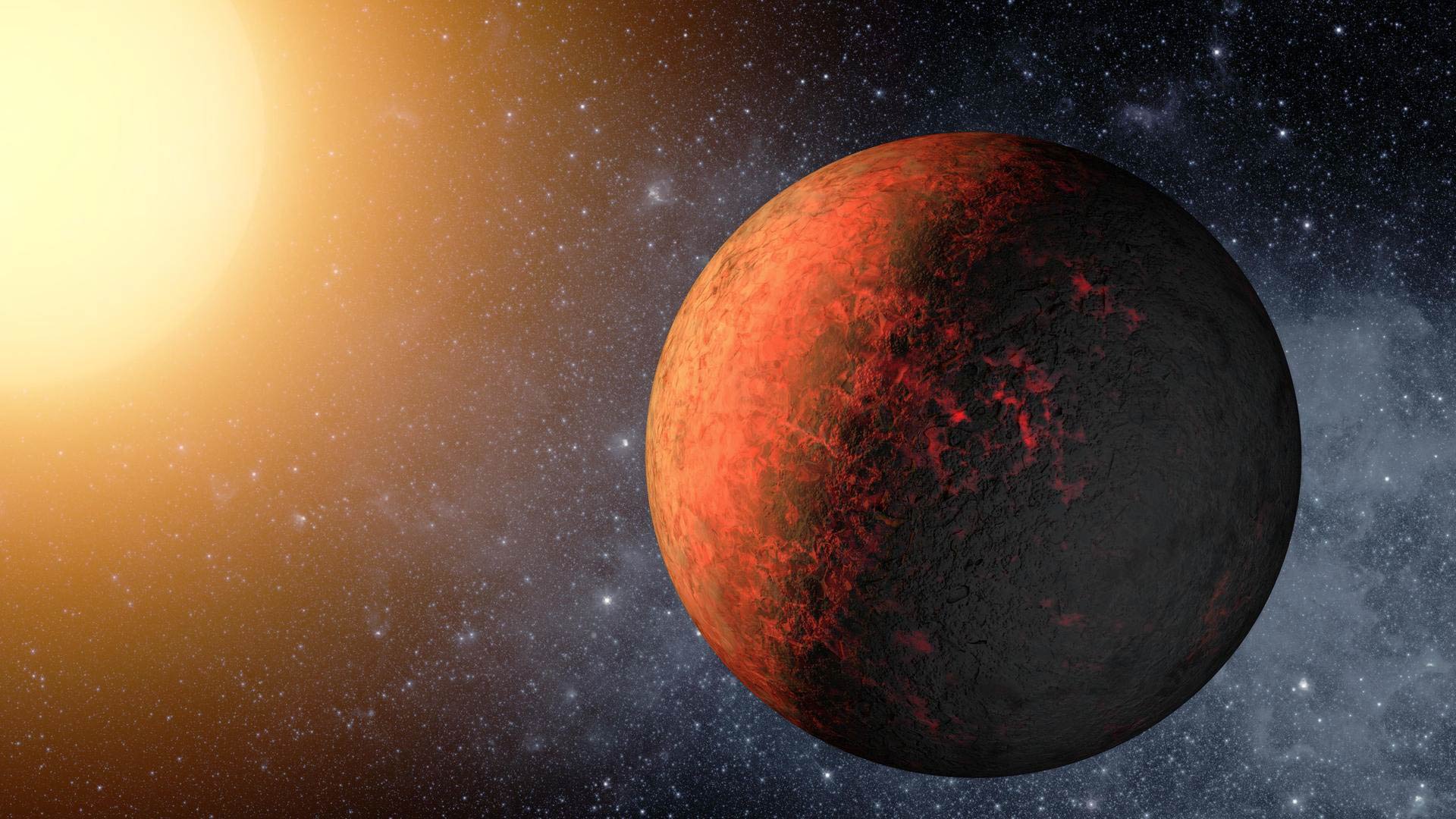

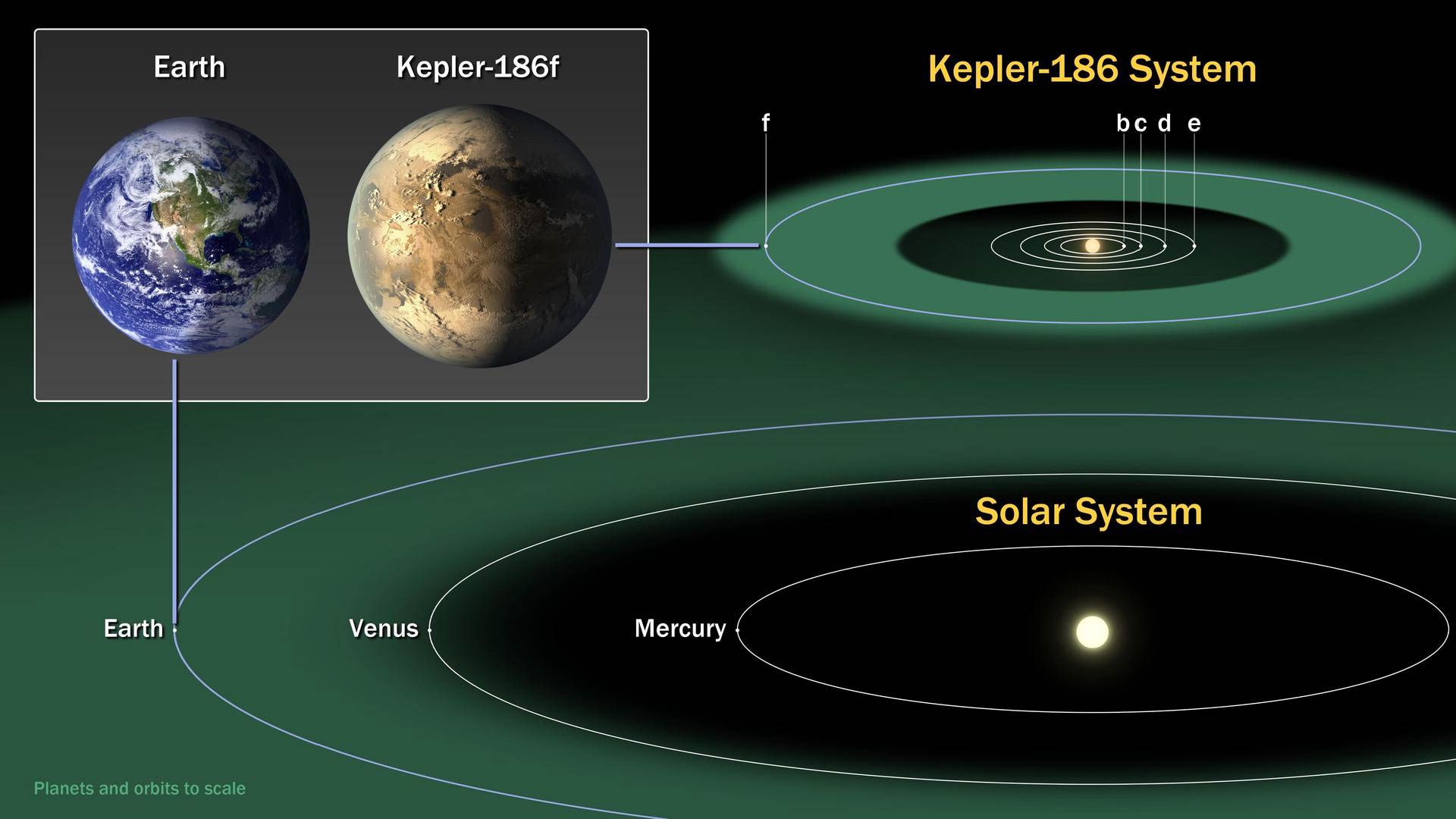

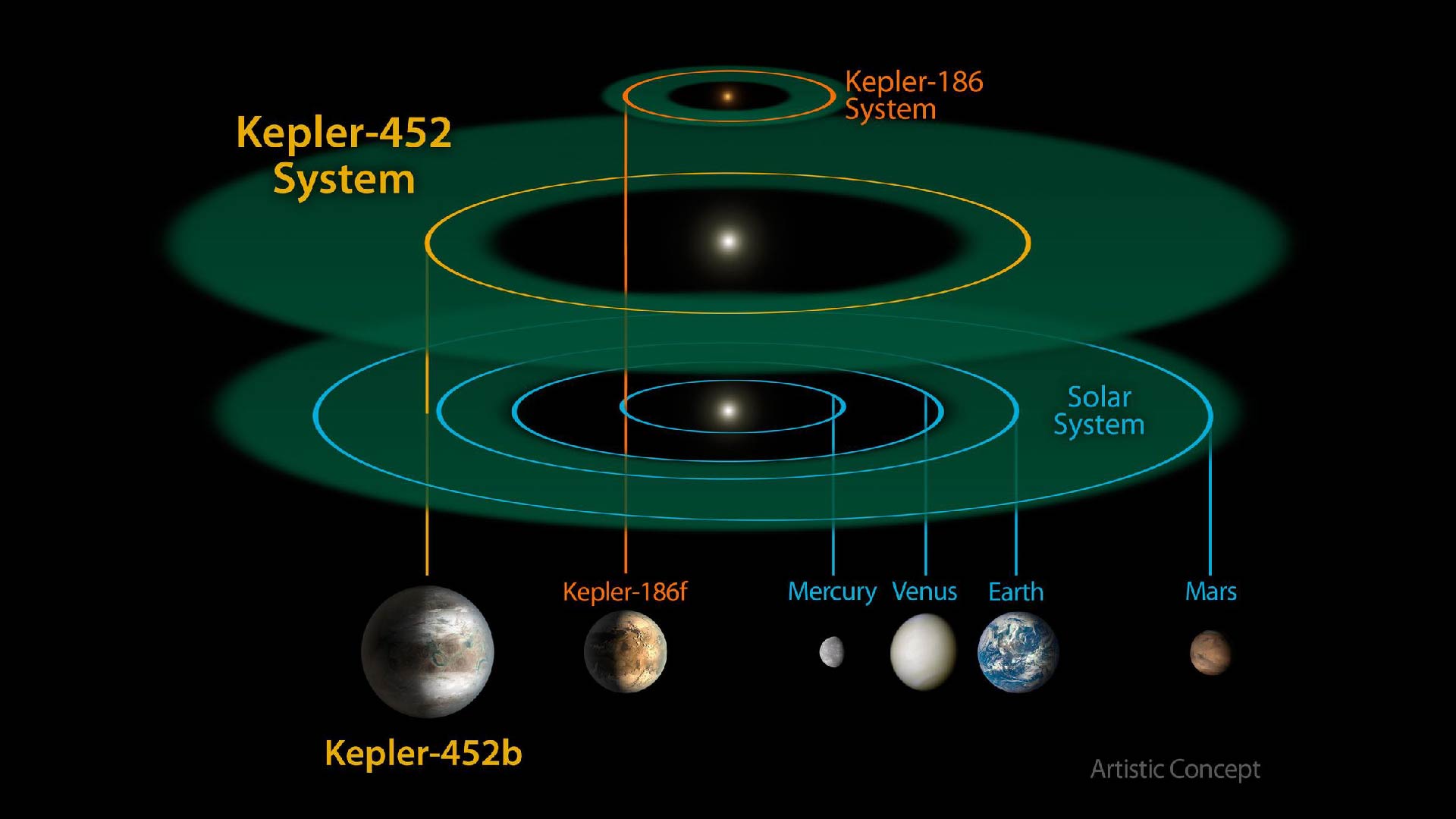

Kepler-186f

If you visited this rocky exoplanet, the first thing you’d notice would be the colors. Because of the way light is reflected on Kepler-186f, any vegetation would appear red, purple or black, according to NASA. First observed in 2014, this planet was the first Earth-sized planet discovered in the habitable zone of another star system.

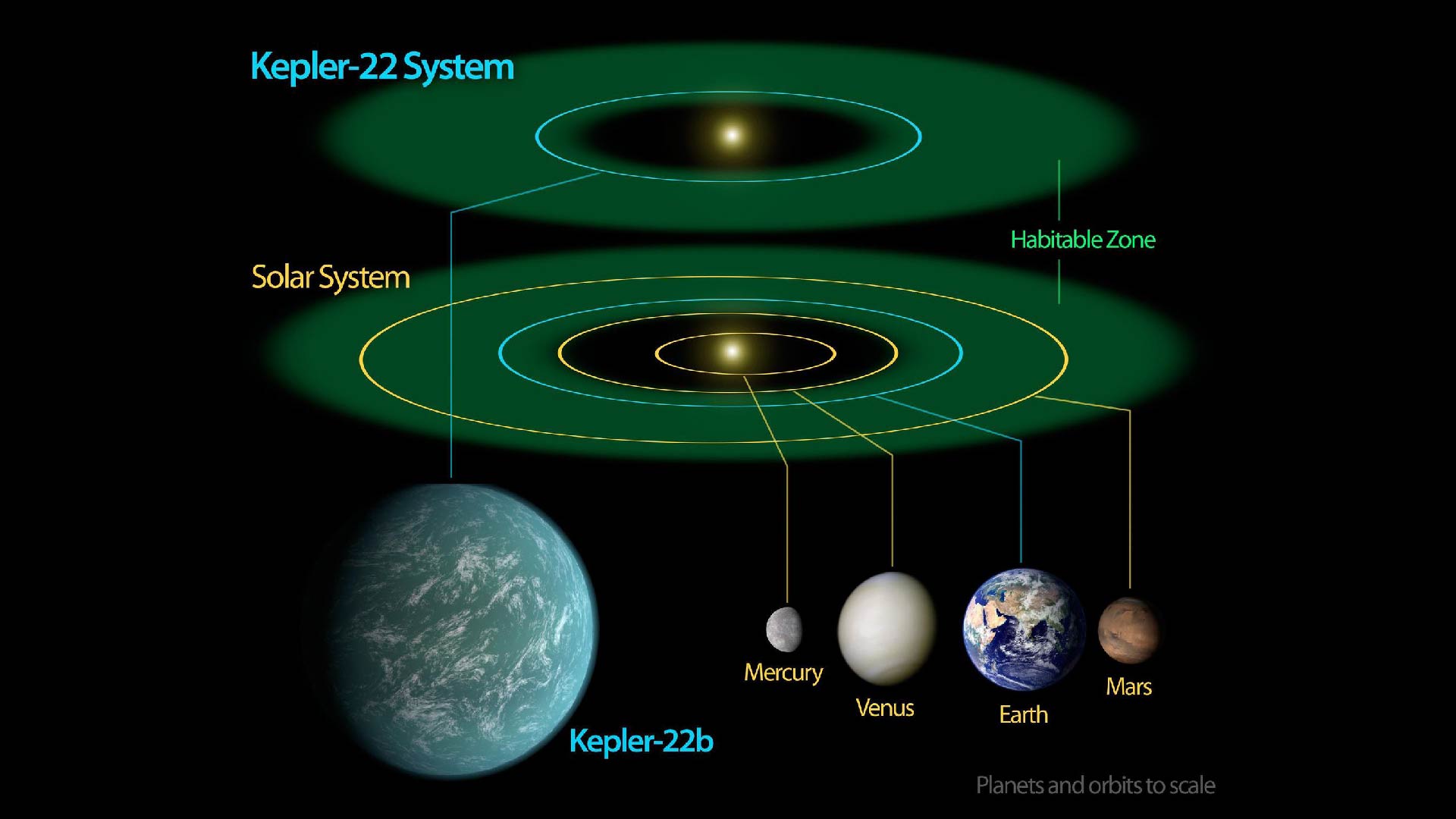

Kepler-22b

On this giant world, night and day each last half the year, with 145 days of total darkness and 145 days of constant sunlight. Still, life could be possible on Kepler-22b, according to NASA. This “super-Earth,” which has a radius 2.4 times that of our planet, likely is covered in an ocean of liquid water and sits at a balmy average surface temperature of 60 degrees Fahrenheit (16 degrees Celsius).

Kepler-452b

This ancient “super Earth” is about 6 billion years old — much older than our planet. It’s also 60% larger, according to NASA. Kepler-452b is located right in the habitable zone of a star similar to our sun.

GJ-486

This exoplanet whizzes around its host star so quickly that a year only lasts 1.5 Earth days, according to Webb Space Telescope. While the surface of the planet is a whopping 800 degrees F (426 degrees C) — likely too hot for life — the James Webb Space Telescope detected hints of water vapor, a potential sign that the planet has an atmosphere.

K2-18b

This exoplanet, which exists 120 light-years away from us, is a vast, cold place. Its radius is more than twice that of Earth and it’s 8.6 times as massive. Its mantle is made of high-pressure ice and its atmosphere is rich in hydrogen. Yet in a 2023 study published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, scientists reported that, using the James Webb Space Telescope, they’d detected organic molecules — the building blocks for life — in the planet’s atmosphere. A follow-up 2025 study has doubled down on the previous findings with an even clearer signal, yet the detection still remains below the threshhold of significance required for a discovery.

Terminator zones

What if, to transition from night into day, you had to travel halfway around the world? For many planets, that’s the reality. These tidally-locked planets have one side that constantly faces their host star. In a 2023 study published in The Astrophysics Journal, scientists proposed that life could exist in the “terminator zones” — the boundary between light and dark — of these seemingly inhospitable worlds.

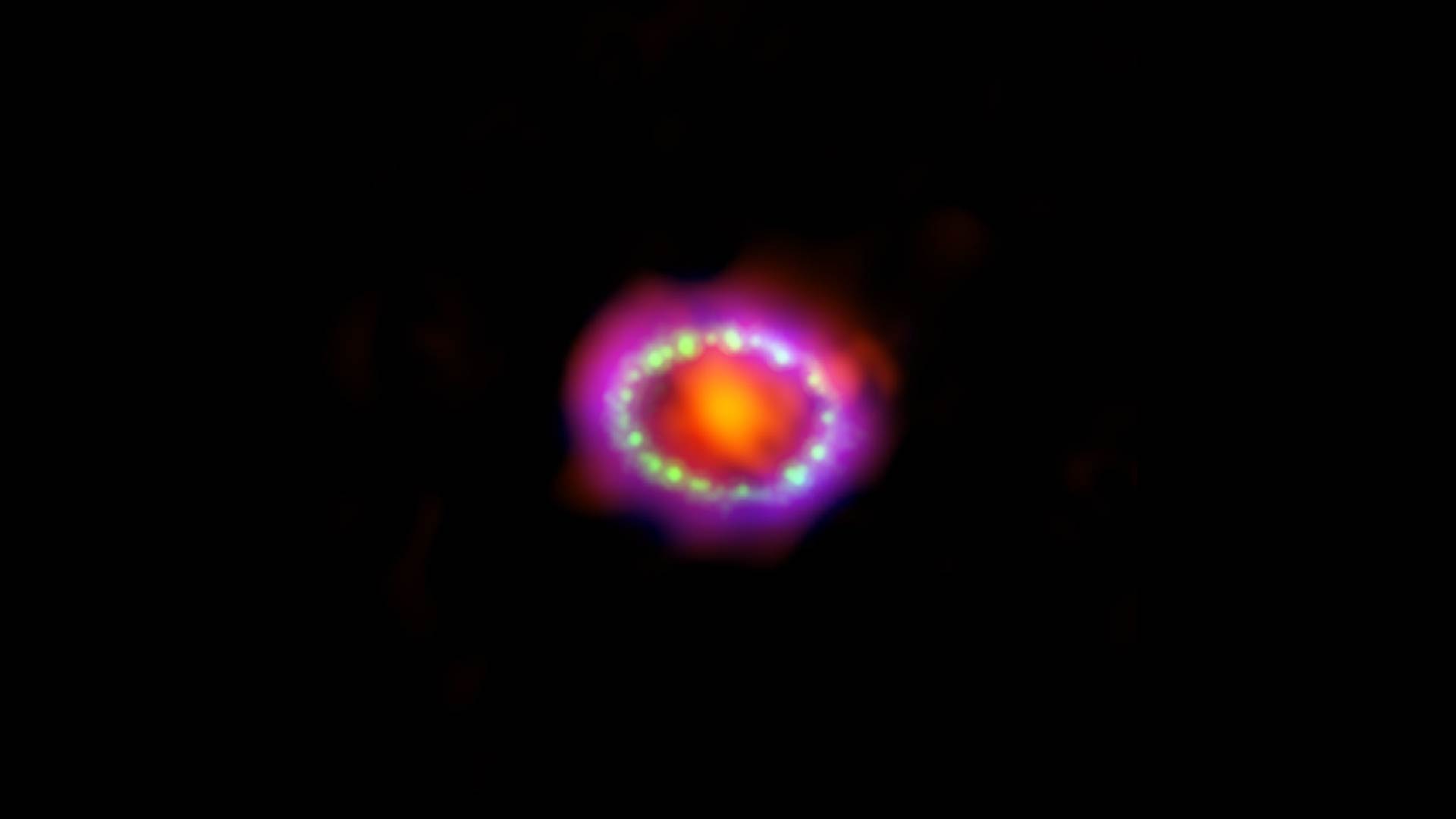

A dying star

In early 2023, a star in the galaxy Messier 101 was observed dying. Though it occurred 25 million light-years away, its demise was pretty hard to miss — it died in a violent explosion called a type-II supernova. That got scientists thinking: what if intelligent life knew that such an event would catch our attention? In a study published in the pre-print database arXiv, scientists proposed searching the area around the supernova for star systems with potentially habitable planets, in case alien civilizations live there and might be trying to send us a message.

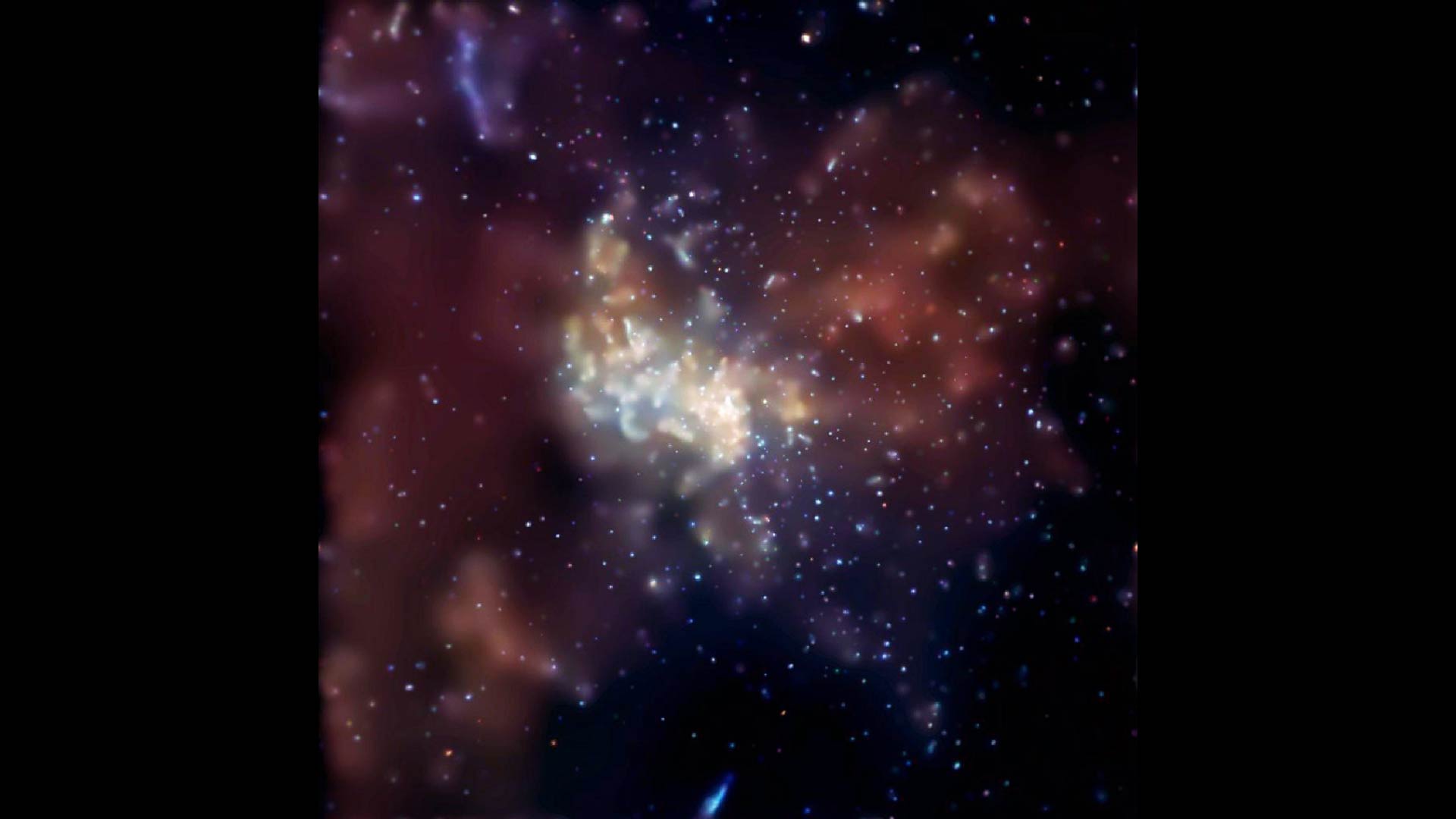

The center of our galaxy

Aliens at the core of the our galaxy would be in a privileged position to catch our attention — they’d be able to reach a vast swath of space by fanning signals outward. That’s why some scientists are turning their search for extraterrestrial life to the middle of the Milky Way. In a recent study published in The Astronomical Journal, scientists reported listening for any narrow-frequency pulses, which are used by humans in radar and stand out against background radio noise in space, coming from this region of our galaxy.

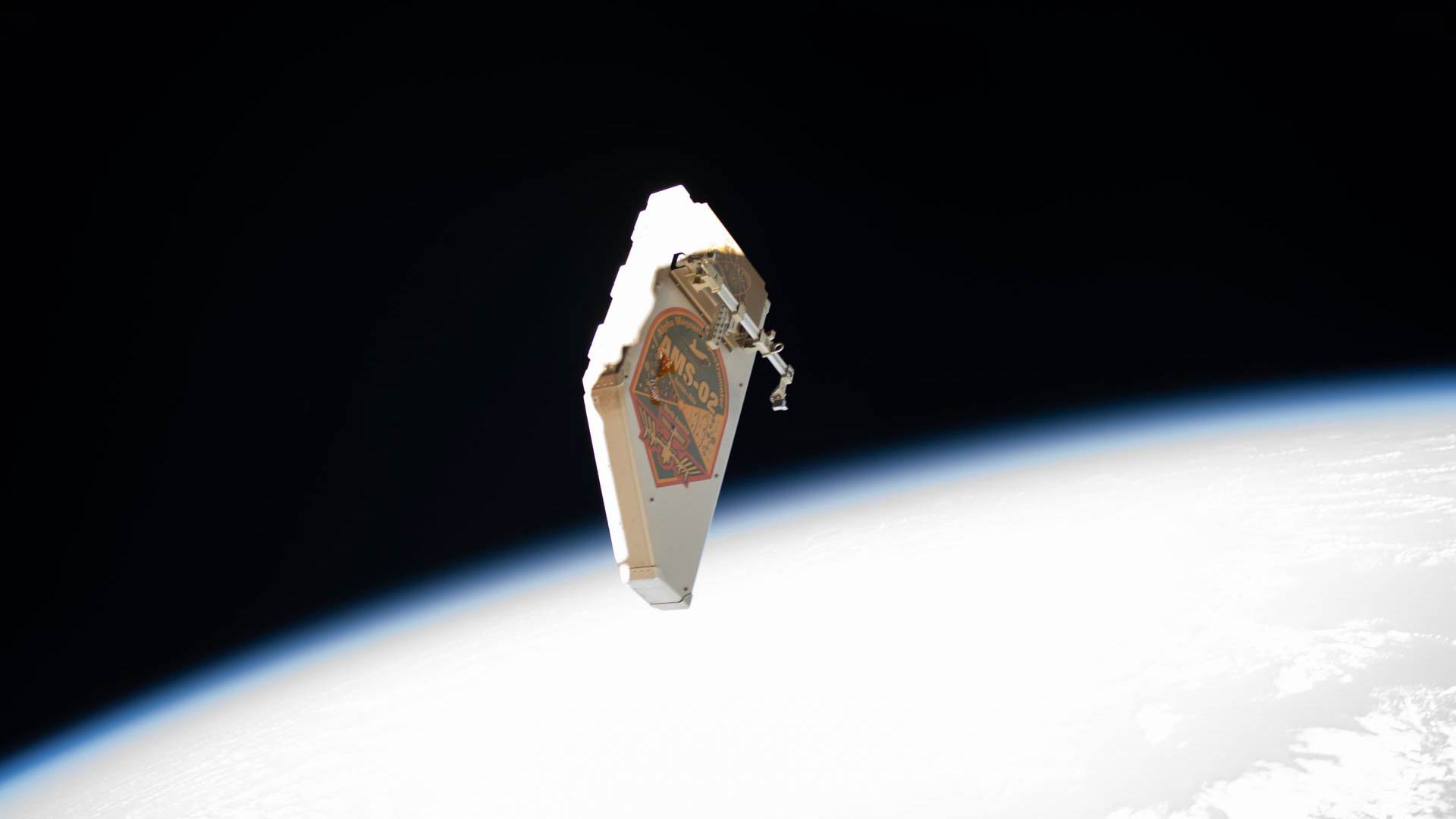

Space junk

What if the debris floating around our planet wasn’t rock, but remnants of alien technology? In a recent study published in the preprint journal arXiv, scientists argued that so-called “interstellar interlopers,” debris from distant star systems, could become trapped in Earth’s orbit — and that included in such debris could be objects crafted by aliens.

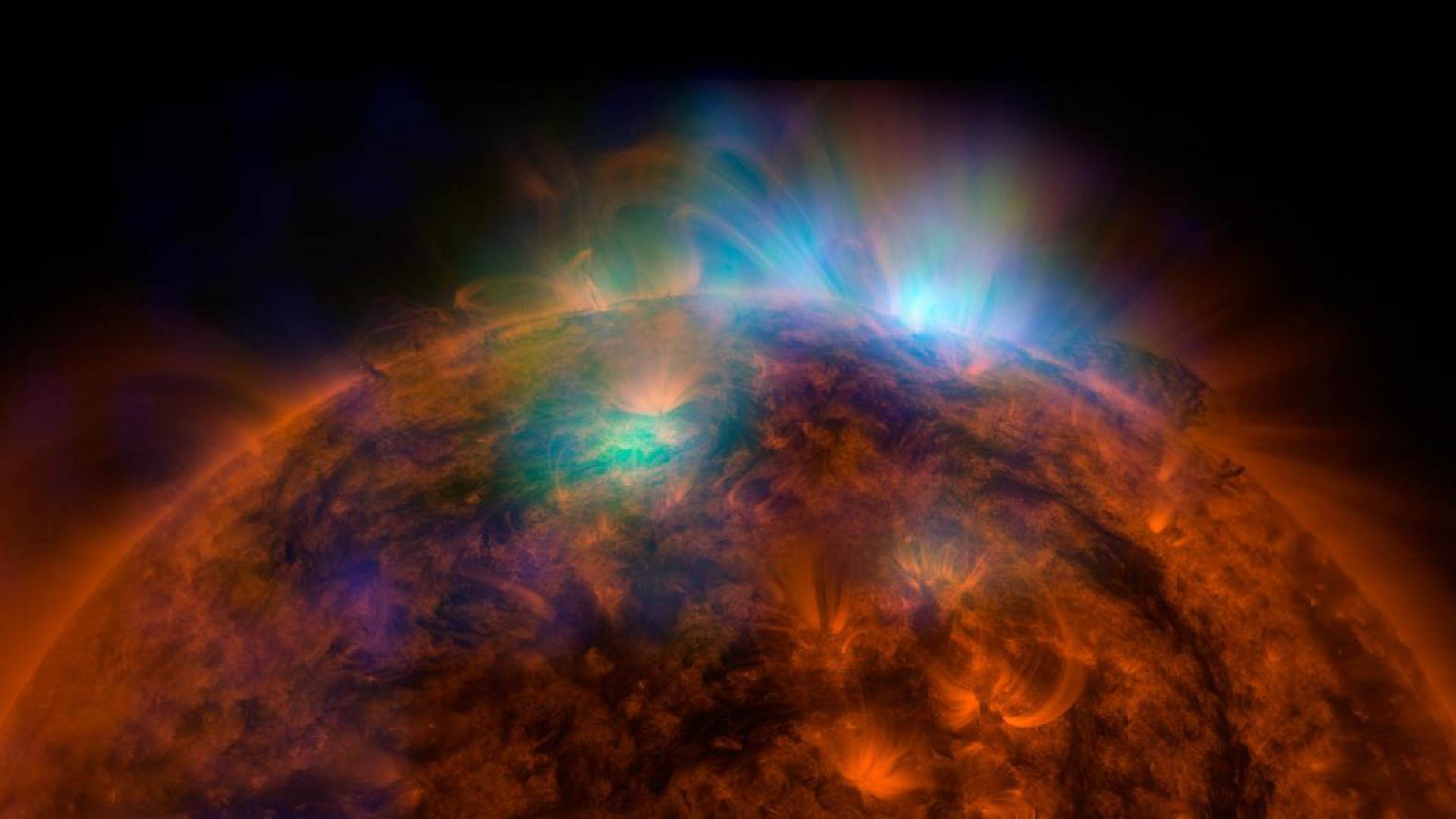

Our sun

If an intelligent lifeform wanted to send us a message, they could hypothetically use our sun as a node in a giant “space internet.” Because of the star’s immense gravity, it bends light, which would allow it to act like a magnifying glass for signals sent across vast distances. In a study published in The Astronomical Journal, scientists reported scanning the sun for such radio signals — but came up short.

Parallel universes

OK, so there isn’t really a way to “search” parallel universes — at least not yet. Still, scientists got pretty close when they ran a massive computer simulation to see what types of universes might be hospitable to life. They found that life might form even in universes that were dense with dark energy, the mysterious force driving the expansion of our universe, which previously wasn’t thought likely.

‘Oumuamua

This oblong object catapulted in front of our sun in 2017 — but it didn’t originate in our solar system. That led one Harvard astrophysicist to argue that such an object was likely a remnant of alien technology. However, most of the scientific community disagrees, LiveScience previously reported. When other scientists used the Murchison Widefield Array telescope to take a closer look, they found no evidence that the object was of artificial origin.

LHS 1140 b

One scientist called this planet the “most exciting” exoplanet of the decade. Located 40 light-years away, it orbits a star just one-fifth the size of our sun and receives less than half the light that Earth receives. This planet isn’t dense enough to be purely rocky, so researchers think it either has abundant liquid water or an atmosphere full of light elements — but it will take further measurements by the James Webb Space Telescope before we have more clarity, Space.com reported.

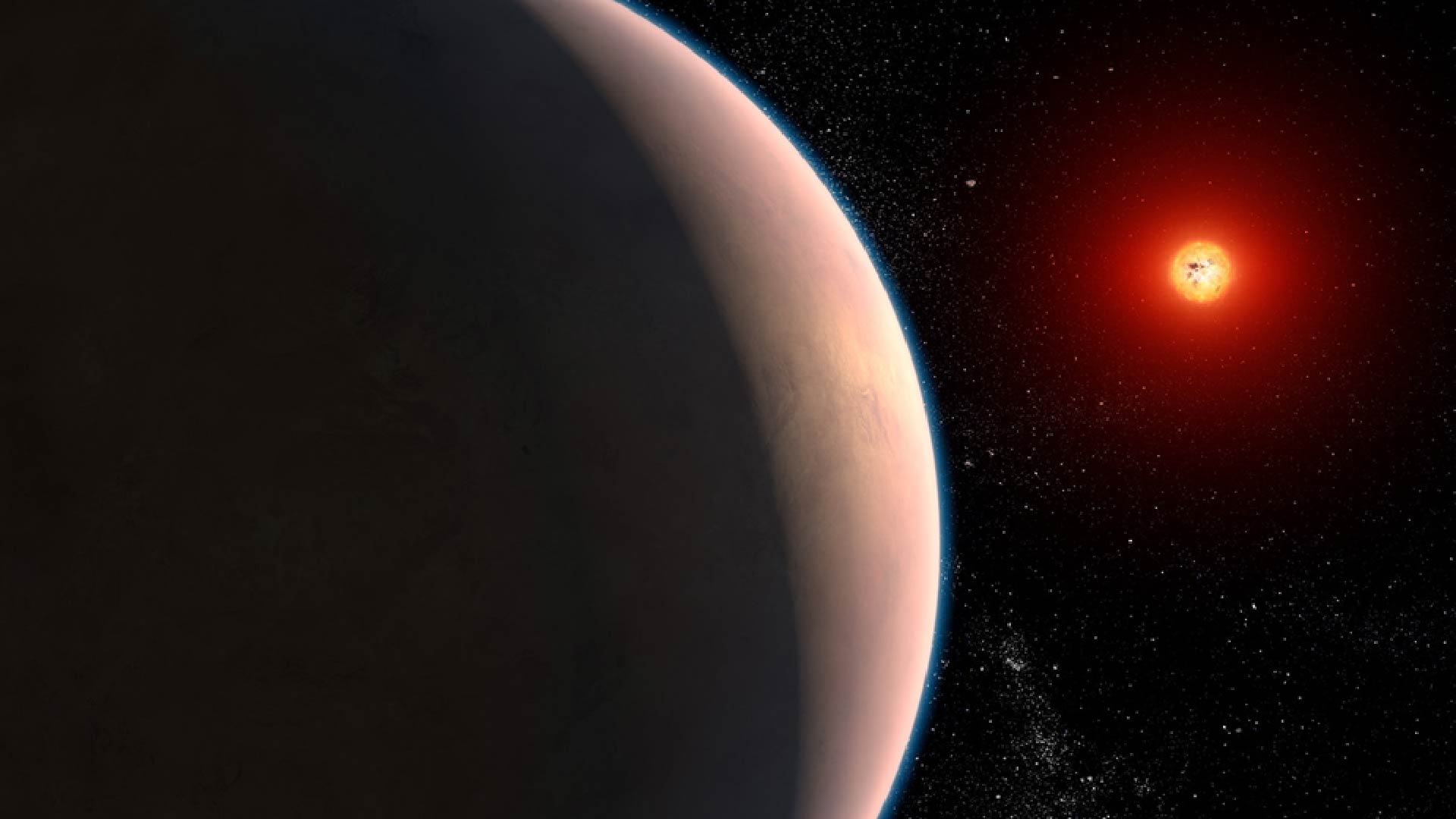

Proxima Centauri b

Located only 4.2 light-years away, Proxima b (as it’s colloquially known) is the closest known exoplanet to Earth. This planet is likely “tidally-locked,” Space.com reported. That means that one of its sides constantly faces the sun, while one always faces away, so there is constant day on one side, and constant night on the other. This planet is in the habitable zone of host star Proxima Centauri, so it’s possible it has liquid water. But it’s also possible that intense radiation has stripped away its atmosphere.

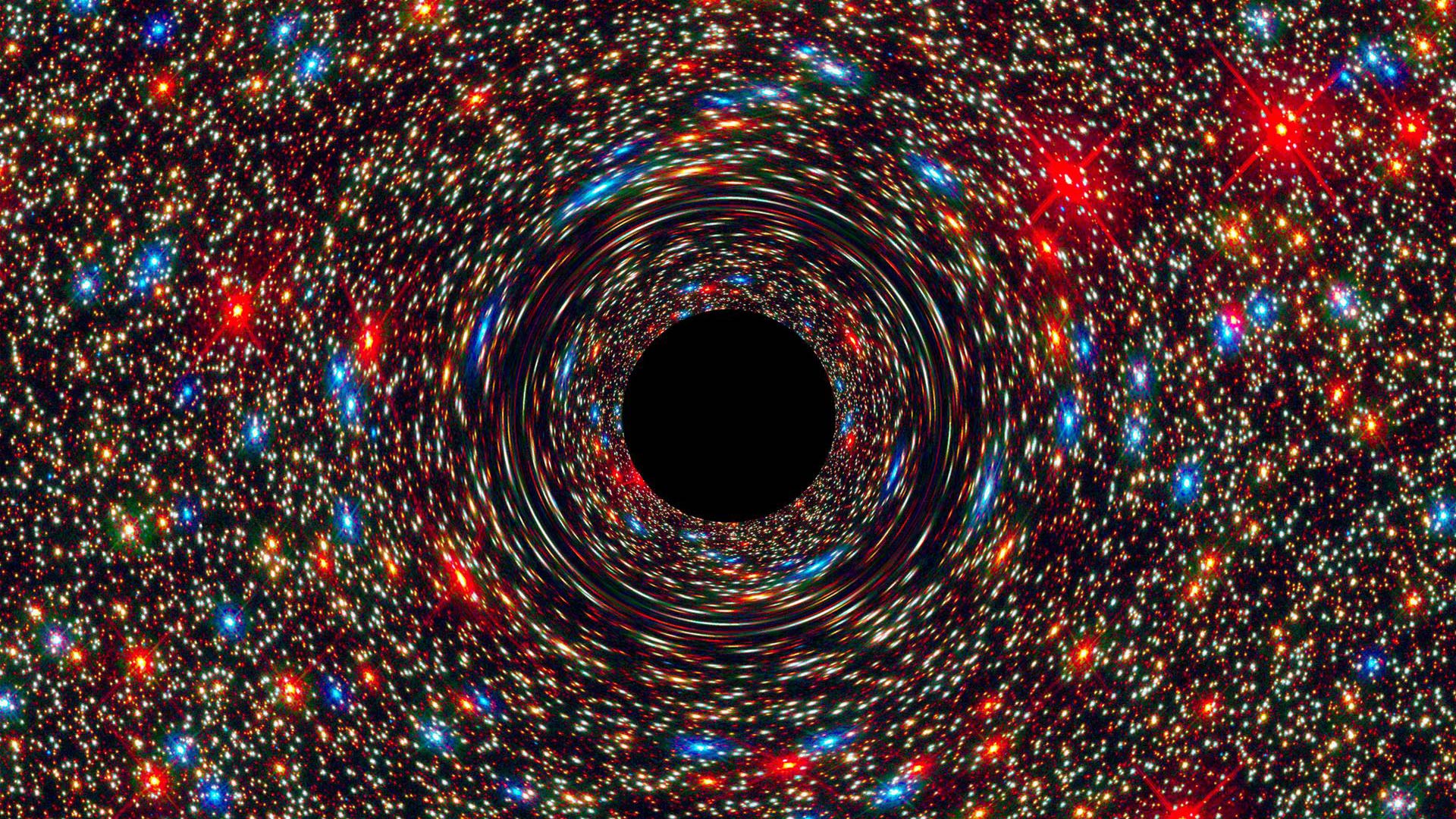

Black holes

No, scientists don’t think life could exist in a black hole — but intelligent civilizations might use the massive celestial bodies as limitless sources of energy, scientists speculated in a 2021 study published in the journal Physical Review D. This method of harvesting power might leave traces outside the “event horizon,” beyond which the black hole’s gravity is too strong for matter and energy to escape. It’s even possible that those traces have already been observed, the scientists argued.

Earth

To learn about life outside our solar system, we should look at… ourselves, scientists proposed at the 52nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in 2021. Observing Earth from the vantage point of another solar system could help us identify signatures of life, which we could then apply to our study of exoplanets.

Messier 13

Somewhere out in space, a radio message sent by a team of scientists in 1974 is hurtling towards the star system Messier 13, also known as the Hercules Cluster. The scientists, who included Frank Drake and Carl Sagan, composed the famous “Arecibo message” in binary code. It depicts a human stick figure, a double helix DNA structure, a model of a carbon atom, and a diagram of a telescope. By the time the message reaches the star cluster, which is 25,000 light-years away, Messier 13 will have moved — but aliens might be able to detect the signal as it sails by, LiveScience reported.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Isobel Whitcomb is a contributing writer for Live Science who covers the environment, animals and health. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Fatherly, Atlas Obscura, Hakai Magazine and Scholastic's Science World Magazine. Isobel's roots are in science. She studied biology at Scripps College in Claremont, California, while working in two different labs and completing a fellowship at Crater Lake National Park. She completed her master's degree in journalism at NYU's Science, Health, and Environmental Reporting Program. She currently lives in Portland, Oregon.