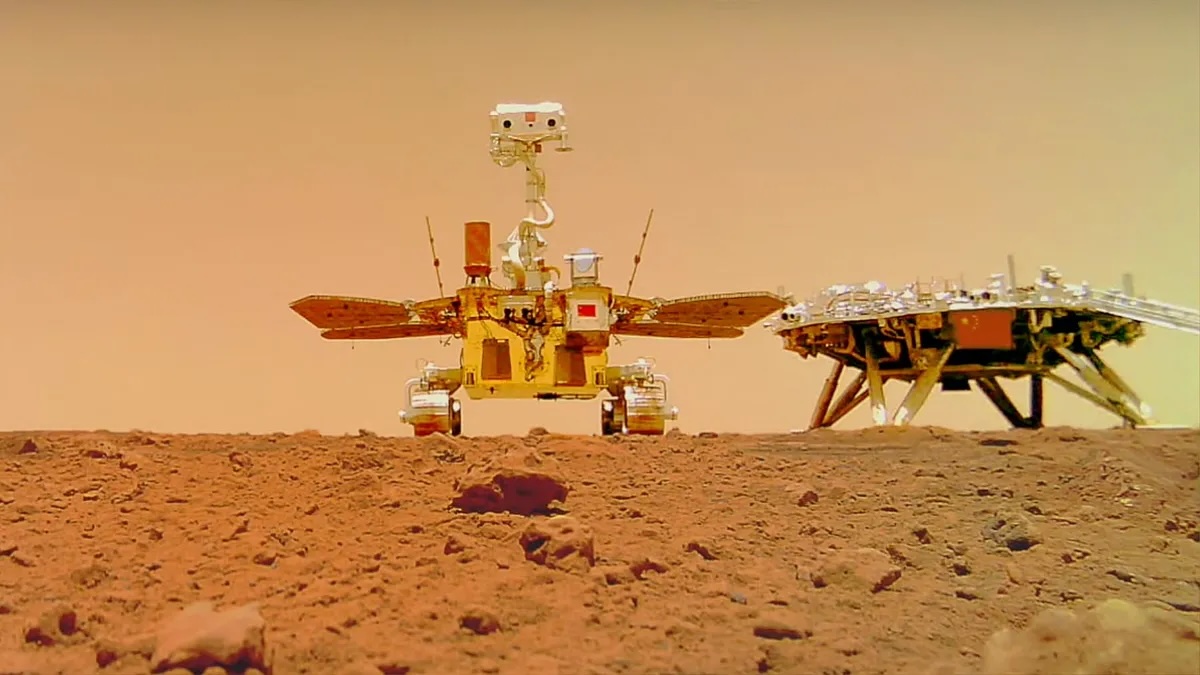

China's Mars rover Zhurong finds possible shoreline of ancient Red Planet ocean

Data from China's Zhurong rover has revealed what appears to be an ancient shoreline streaking through Mars' northern hemisphere.

Happy Martian New Year! Today marks the start of a new year on the Red Planet, the 38th since humans began counting in 1956.

The Martian new year begins with data from a now-defunct rover spotting what appears to be an ancient shoreline streaking through Mars' northern hemisphere. Scientists studying data sent home by China's Zhurong rover say the findings offer fresh support to the decades-old hypothesis that an ancient ocean covered the Martian north billions of years ago.

Since Zhurong landed in 2021 — in one of the largest and oldest impact basins on Mars, known as Utopia Planitia — the rover has traveled about 1.24 miles (2 kilometers) studying the geology of its surroundings in search of signs of water or ice.

By combining observations from the rover's onboard cameras and ground-penetrating radar with remote sensing data from orbiting satellites, Bo Wu at Hong Kong Polytechnic University and his colleagues spotted several water-related features around the rover's landing area. They included crater-like pitted cones, troughs, sediment channels and mud volcano formations that the team interprets as evidence of an ancient coastline.

Based on the composition of surface deposits in the area, the ocean likely existed around 3.68 billion years ago, according to a paper describing the findings, which was published in the journal Scientific Reports.

The team thinks a variety of water-related minerals such as hydrated silica started forming on the ocean bed around this time. "The water was heavily silted, forming the layering structure of the deposits," study co-author Sergey Krasilnikov of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University told Reuters.

The ocean then froze for about 10,000 to 100,000 years — a relatively short period in geologic timescales, etching out the observed coastline before drying out, roughly 260 million years later.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The findings not only provide further evidence to support the theory of a Martian ocean but also present, for the first time, a discussion on its probable evolutionary scenario," Wu told New Scientist.

However, not everyone is convinced yet that Zhurong's data conclusively points to an ancient shoreline. Benjamin Cardenas of the Pennsylvania State University, who has studied evolution of Martian landscapes, told AFP that erosion taking place over billions of years would most certainly destroy fragile, eons-old signs of a shoreline. Wu agreed, though noting it is nevertheless possible that subsequent asteroid strikes resurfaced bits of the shoreline spotted by Zhurong.

The presence of water, a key ingredient for life as we know it, and an ancient ocean on Mars suggests the Red Planet was once capable of harboring conditions friendly toward microbial life. Scientists continue to piece together just how all that water began disappearing into space approximately 3 billion years ago. Much of its escape is known to have been accelerated by a young sun's frequent solar storms that stripped away Mars' once-thick atmosphere.

Scientists also think, at least some of the ocean must have disappeared underground. Data from NASA's Insight lander recently found enough water to cover Mars with an ocean between one and two kilometers deep (0.62 and 1.2 miles) had percolated into the planet's crust, where it got stored in tiny cracks and pores. While Insight did not find any evidence for Martian life, "at least we have identified a place that should, in principle, be able to sustain life," Michael Manga of the University of California, one of the study authors, said in a previous statement.

Scientists stress that incontrovertible ground truth about Mars' water history can be established only after some of the samples from the planet are brought back to Earth, where scientists can perform the kind of detailed analysis not possible with instruments onboard the rovers.

Such analyses — and answers to the decades-old mystery of disappearance of Martian water — might be possible as soon as 2031. China recently announced it has advanced its Tianwen 3 Mars sample return mission by two years, to 2028, meaning the nation could bring 500 grams (17.6 ounces) of Martian surface samples to Earth by 2031.

If the mission goes to plan, the samples could be delivered to Earth well before the joint NASA-European Space Agency Mars Sample Return (MSR) program does so. The complex U.S. MSR program is in the midst of a major overhaul after severe cost and schedule overruns made the original mission framework unaffordable. NASA is aiming to determine by the end of the year how to simplify the mission's architecture and reduce costs such that it can bring samples scooped by the car-sized Perseverance rover to Earth before 2040, agency officials said late last month.

However, the entire MSR program is likely to soon get a hard look by the President-elect Donald Trump's administration. SpaceX, whose owner Elon Musk is Trump's wealthiest supporter and is gaining influence within the federal government, is one of the seven companies that submitted a proposal to NASA outlining a simpler sample return mission plan using SpaceX's megarocket Starship. Experts say it now makes little sense to spend billions of dollars on an independent robotic sample return mission when astronauts can simply bring the samples inside Starship.

"I see a very dim future right now for MSR as an independent project managed by NASA," Casey Dreier, who is the chief of space policy at The Planetary Society, told Space.com in a recent interview.

A study about these results was published on Nov. 7 in the journal Scientific Reports.

Originally posted on Space.com.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Space.com, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social