Gigantic 'spiderwebs' on Mars are the next big target for NASA's Curiosity rover, agency reveals

Curiosity has just finished the latest leg of its 12-year Mars mission and will now set out to explore miles of web-like surface features left behind by ancient water on the Red Planet. The zig-zagging rocks could also provide clues about whether Mars once harbored extraterrestrial life.

The ever-reliable Curiosity rover is about to begin a new quest to study giant "spiderwebs" on Mars' surface, after successfully concluding its previous mission, NASA has announced. The web-like rocks span for miles and may hold secrets about the Red Planet's watery past.

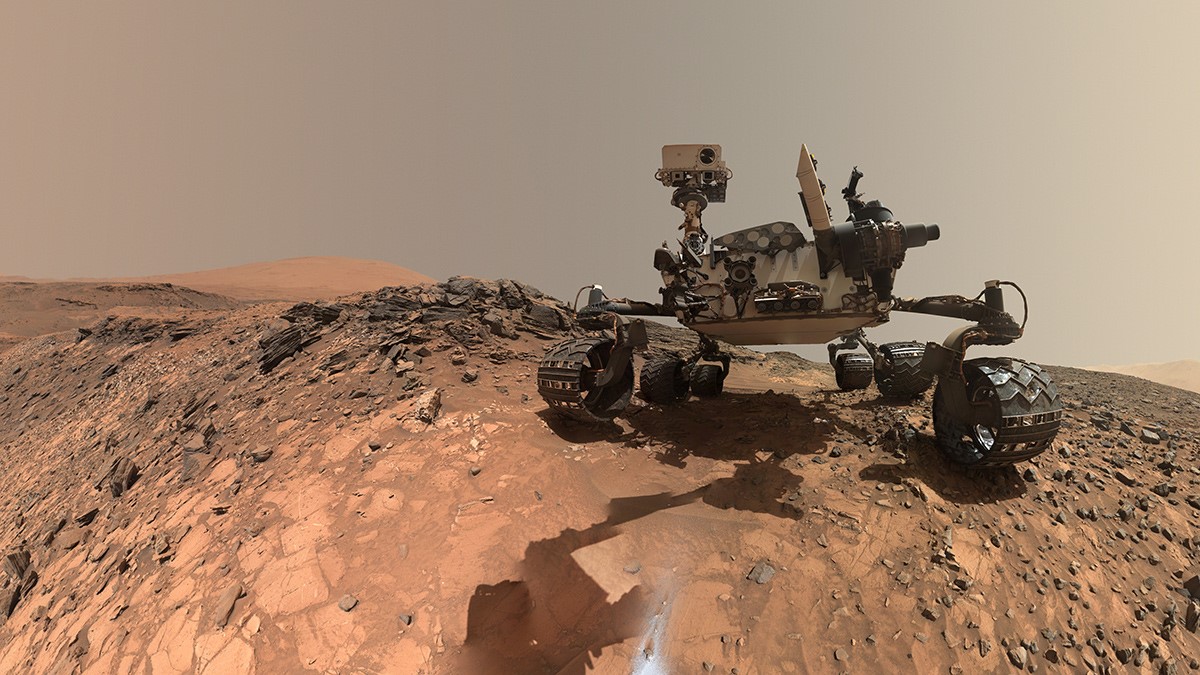

Over the last year, Curiosity has been exploring Gediz Vallis — a channel carved into the steep slopes of Mount Sharp at the heart of Gale Crater. During this stage of its 12-year mission on Mars, the rover made some important discoveries, including accidentally unveiling crystals of pure sulfur and finding "wavey" rocks left behind by an ancient lake. Mission scientists also first noticed a large hole in one of the rover's wheels as the wandering robot traversed this region's steep slopes.

But the rover's time in Gediz Vallis is about to come to a close. On Nov. 18, NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) released a final 360-degree "selfie" of the area taken by Curiosity as it prepared to head off on the next leg of its epic journey, which has already lasted a decade longer than initially expected.

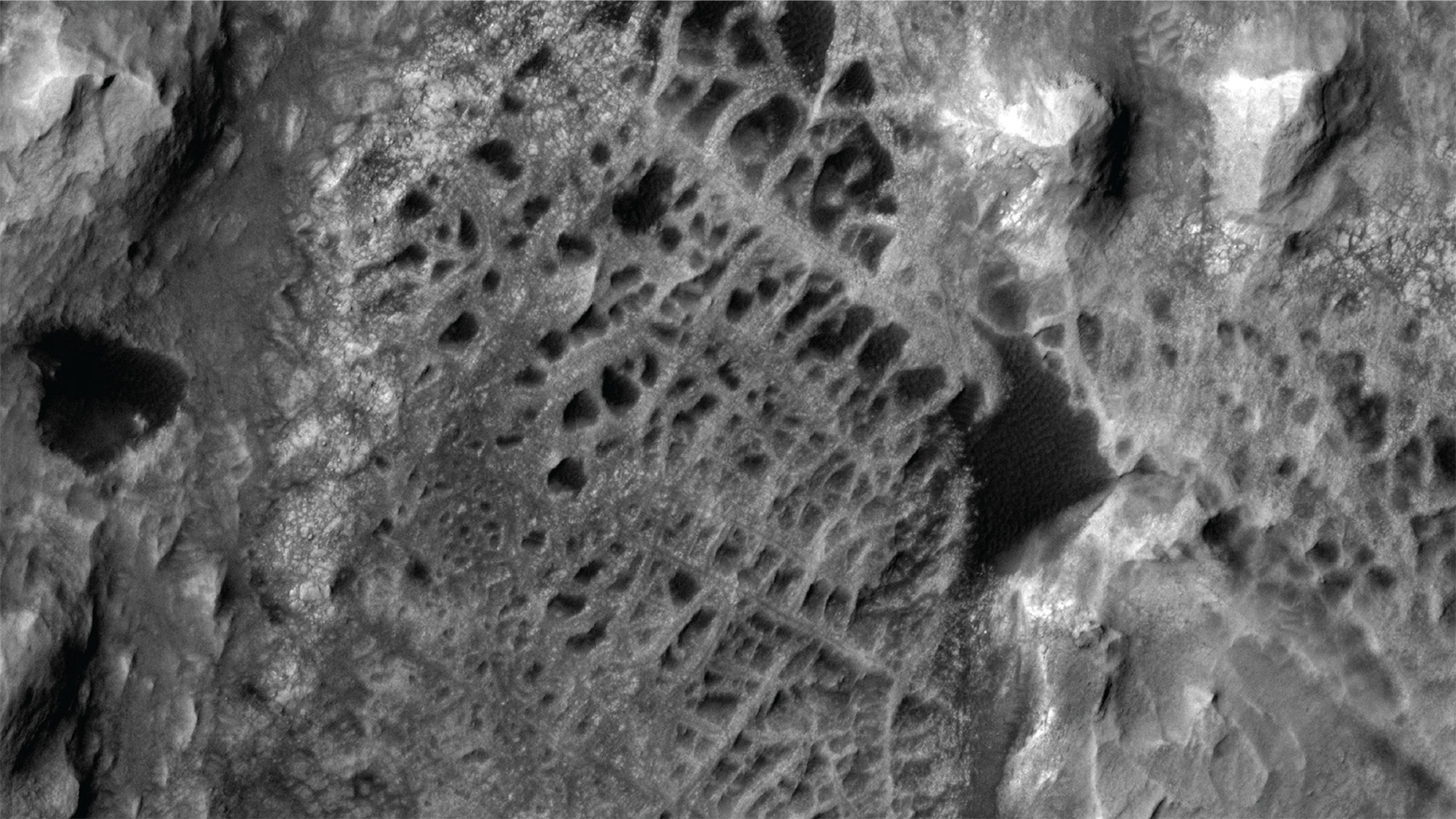

Curiosity's next target is a large collection of spiderweb-like surface features, known as "the boxwork," spanning between 6 and 12 miles (10 and 20 kilometers) across. This unusual patchwork of zig-zagging rocks, or boxwork deposits, was first spotted decades ago but has never been studied up close, according to a JPL statement.

The web-like features should not be confused with the infamous "spiders on Mars" — a geological feature created when carbon dioxide ice on the planet's surface sublimates, or turns into gas from a solid. Scientists recently recreated these strange features on Earth for the first time.

Related: 32 things on Mars that look like they shouldn't be there

Boxwork deposits are also found in caves on Earth. They form when calcite-rich water fills gaps between rocks and hardens before eventually eroding away, creating "thin blades of crystalline material protruding from rocky walls" similar to stalactites and stalagmites, according to the National Speleological Society. The best examples of this on our planet are found in Wind Cave National Park in South Dakota, according to the U.S. Geological Service. However, terrestrial boxwork features are never more than a few feet wide.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Martian boxwork, which has been identified at several locations across the Red Planet, is believed to form via a similar process as terrestrial boxwork. However, instead of water dripping through caves, the sprawling mineral veins were left behind by the last remnants of ancient, mineral-rich lakes and oceans.

Researchers hope that Curiosity will learn more about exactly how this happened and what it can tell us about Mars' watery past. Mission scientists are particularly interested in the minerals that make up these web-like structures because they could shed light on whether extraterrestrial life once existed on the Red Planet.

"These ridges will include minerals that crystallized underground, where it would have been warmer, with salty liquid water flowing through," Kirsten Siebach, a Curiosity mission scientist at Rice University in Houston who has been studying the area, said in the statement. "Early Earth microbes could have survived in a similar environment. That makes this an exciting place to explore."

Curiosity will arrive at the boxwork at some point in early 2025.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.