NASA Mars samples, which could contain evidence of life, will not return to Earth as initially planned

NASA is looking for a new way to get its precious Mars samples back to Earth.

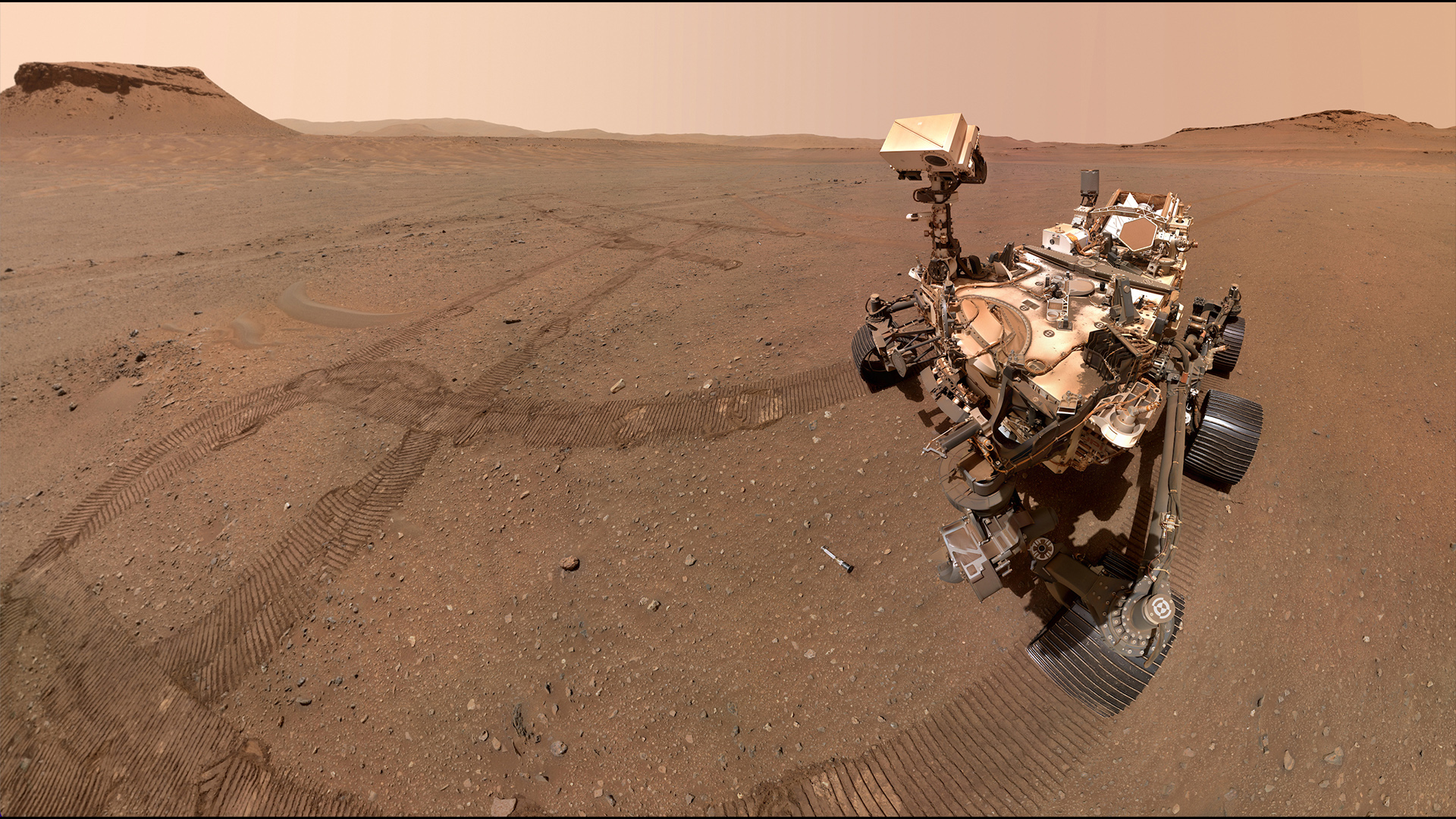

Those samples are being collected by the Perseverance rover in Mars' Jezero Crater, which hosted a lake and a river delta billions of years ago. Getting ahold of the samples is one of NASA's top science goals; studying pristine Red Planet material in well-equipped labs around the world could reveal key insights about Mars — including, perhaps, whether it has ever hosted life, NASA officials say.

The agency has had a Mars sample-return (MSR) architecture in place for some time now, but repeated delays and cost overruns have rendered the original plan impractical, NASA officials announced on Monday (April 15).

"The bottom line is that $11 billion is too expensive, and not returning samples until 2040 is unacceptably too long," NASA chief Bill Nelson said during a call with reporters.

That price tag is the upper-end estimate calculated by an independent review board, which released its findings last September. For perspective: A study from July 2020 estimated the total cost of MSR to be between $2.5 and $3 billion.

A team from within NASA analyzed those September results, determining that the agency won't be able to get Perseverance's samples back to Earth until 2040 with the established architecture. This conclusion cited reasons such as current budget constraints and the desire not to cannibalize other high-priority science efforts, like the Dragonfly drone mission to Saturn's huge moon Titan.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

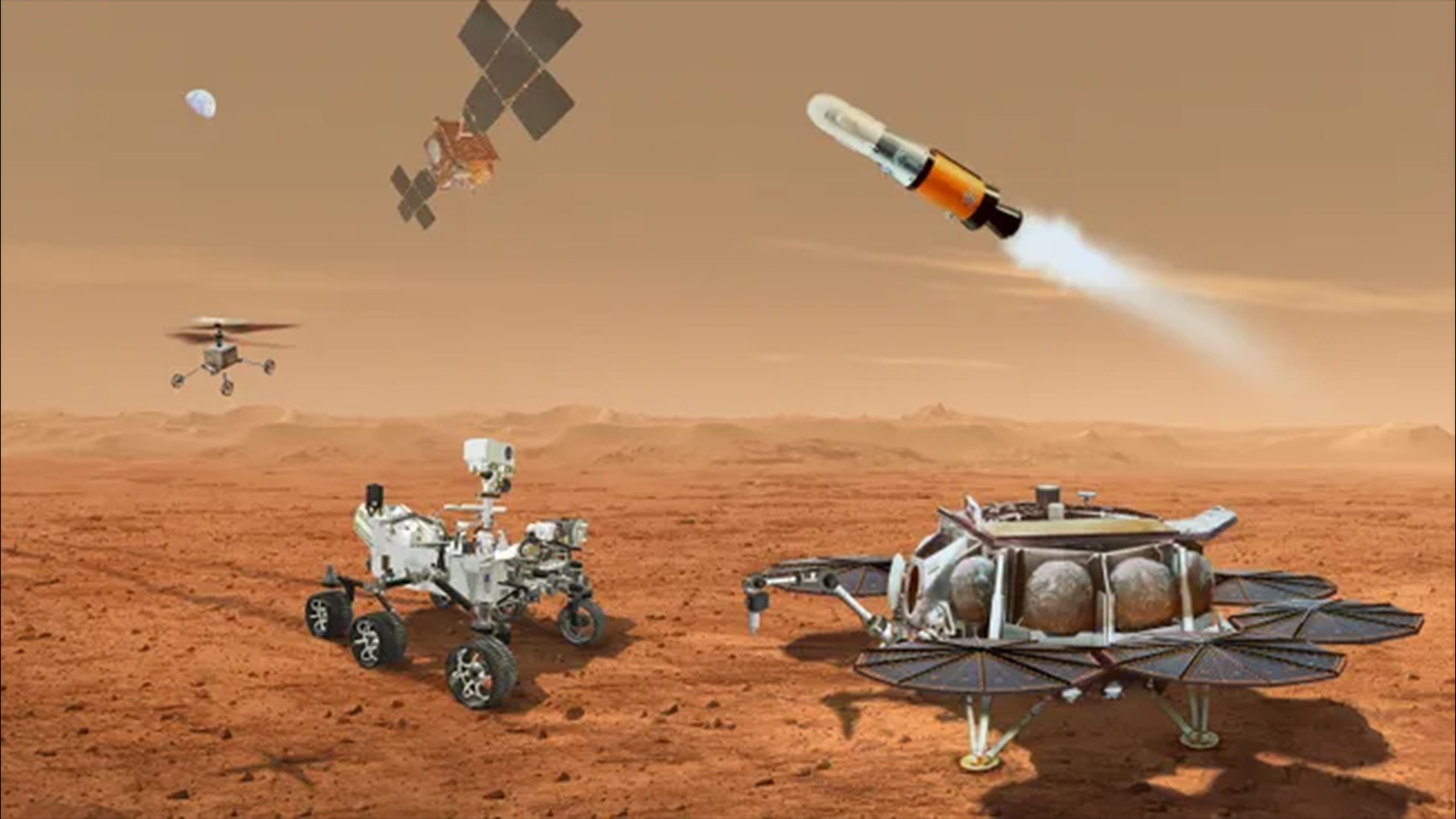

The established architecture, by the way, would have sent a NASA-built lander to Jezero Crater. This lander would have brought with it a rocket called the Mars Ascent Vehicle (MAV) and, potentially, several small retrieval helicopters akin to NASA's pioneering Ingenuity rotorcraft.

The idea was for Perseverance to drive its samples over to the lander, then load them into the MAV. The retrieval choppers may have done some of this loading work as well, especially if Perseverance wasn't in great shape by the time the lander arrived. The MAV would then have launched the samples into Mars orbit, where a spacecraft built by the European Space Agency would have snagged the container and hauled it back toward Earth.

NASA is now seeking a new way forward, however, in an attempt to cut costs and get the samples here sooner. Saving money will aid other agency science projects, and speeding up the timeline could help the agency plan out crewed Mars trips down the line.

"That is unacceptable, [to] wait that long," Nelson said today. "It's the decade of the 2040s that we're going to be landing astronauts on Mars."

The wheels on the new plan (which may retain elements of the old) are already turning. NASA is asking the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California — its lead facility for robotic planetary exploration — and other agency research centers for innovative MSR ideas, Nelson said today.

NASA is also looking to private industry: The agency plans to release a solicitation for new ideas from the commercial sector tomorrow (April 16), Nicky Fox, associate administrator of the agency's Science Mission Directorate, said during today's call.

NASA will hold an industry day on April 22 and accept proposals through May 17, she added. The goal is to have enough information on hand by late fall or early winter to begin charting a new path forward on MSR. "We're opening this up to everyone, because we want to get every new and fresh idea that we can," Nelson said.

It's unclear at this point, of course, what that new path will look like. But Fox previewed some possibilities, such as a smaller and cheaper MAV and a descoped sample-return tally (from 30 of Perseverance's sealed tubes to some unspecified lower number). Fox and Nelson both stressed that MSR remains a high priority for NASA, despite the difficulty of the task — humanity has never launched a rocket from the surface of another planet, after all (though three countries have launched from the moon) — in addition to the problems the project has experienced so far.

"I think it's fair to say that we are committed to retrieving the samples that are there — at least some of those samples," Nelson said. "We are operating from the premise that this is an important national objective."

Originally posted on Space.com.