Did Venus ever have oceans to support life, or was it 'born hot'?

"We would have loved to find that Venus was once a planet much closer to our own, so it’s kind of sad in a way to find out that it wasn't."

Scientists have poured cold water on the idea that Venus could once have supported life. The disappointing revelation emerged from the fact it appears water oceans could never have existed on the surface of our neighboring planet.

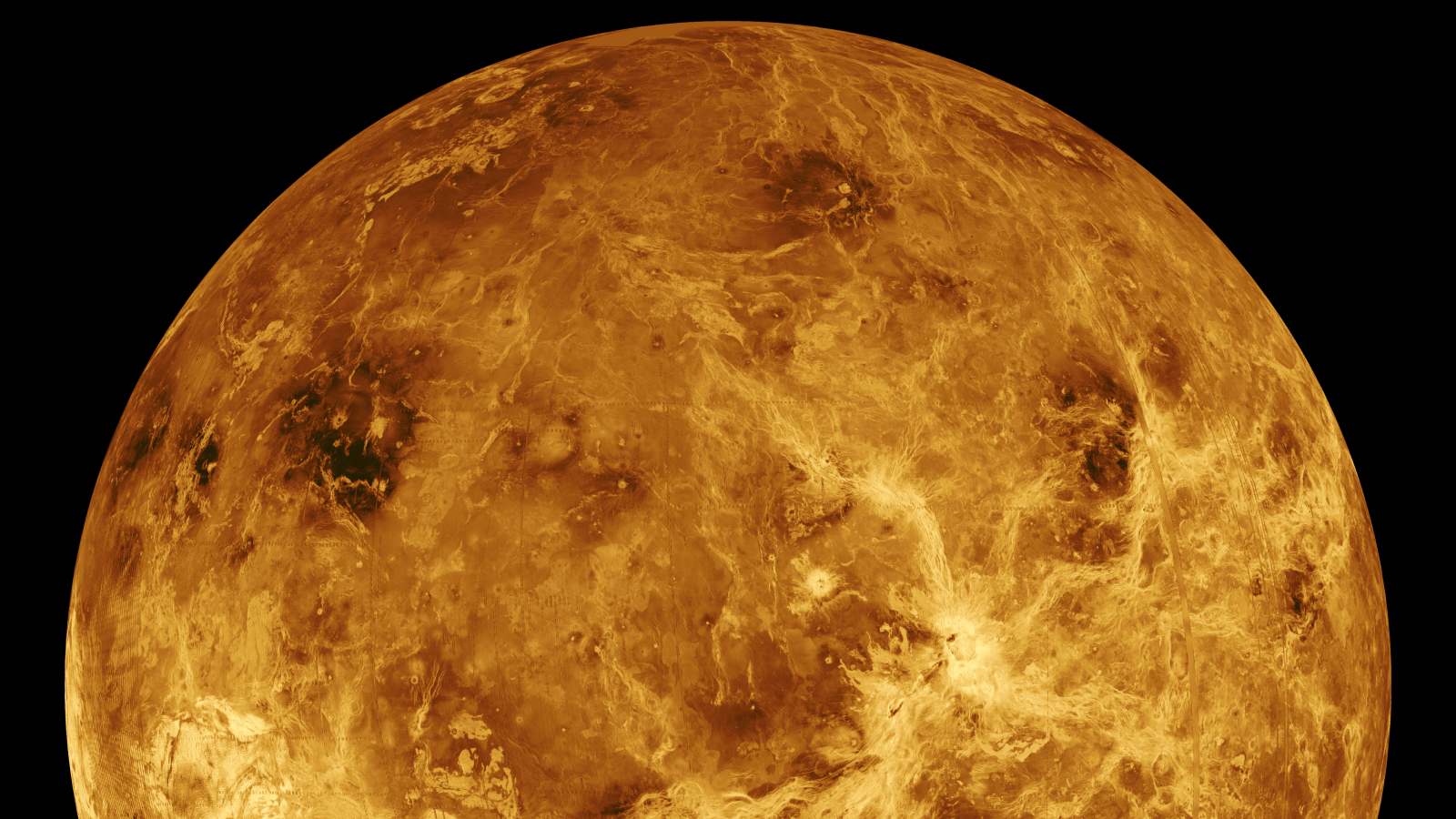

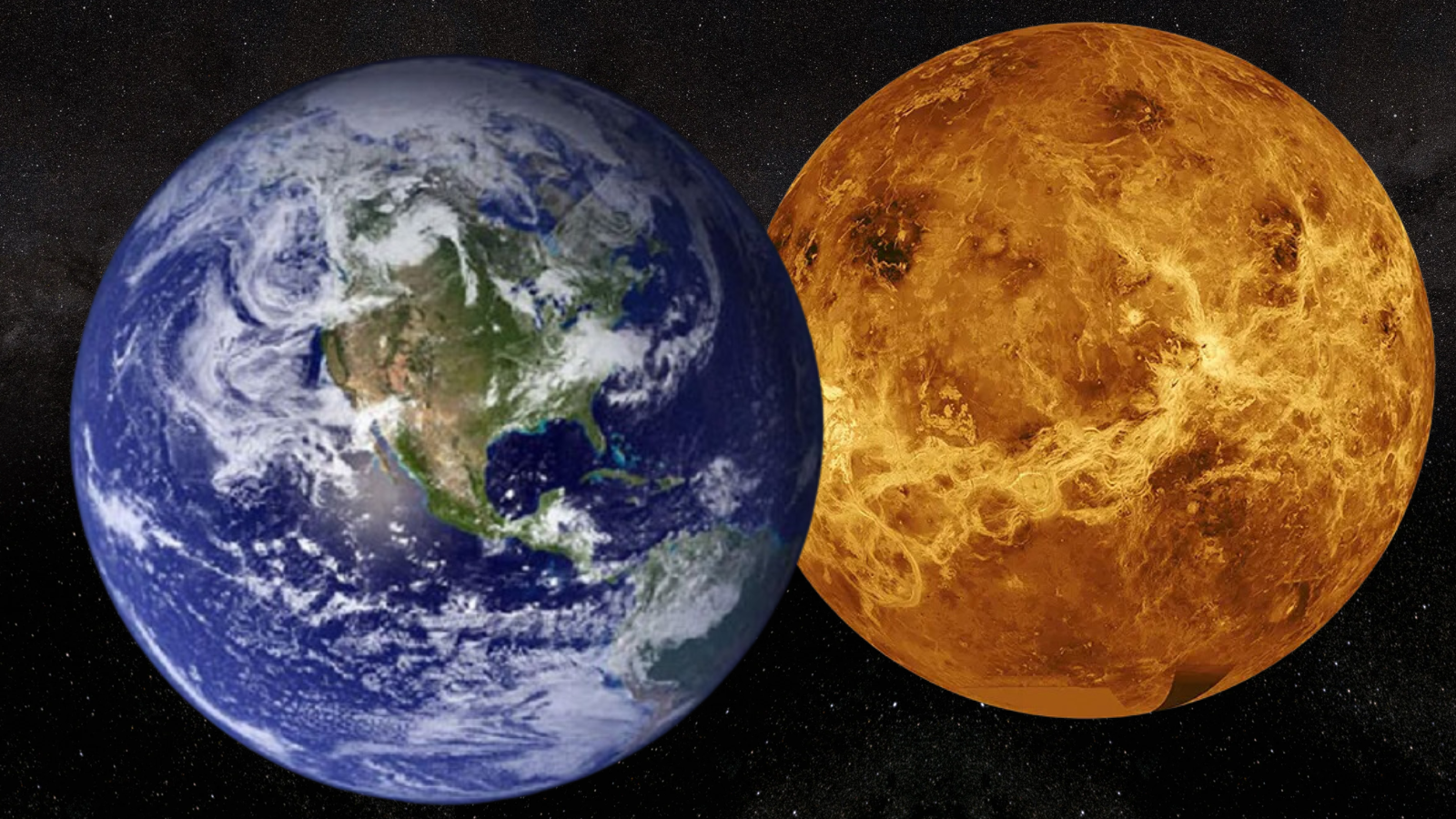

Venus is often referred to as Earth's "evil twin" because, despite it being a virtual hellscape today, it is believed that our neighbor was much more like our planet in its ancient past.

This new research suggests that Venus was always a hellish planet, and despite its similar mass and distance from the sun to Earth, it was never a twin to our planet in other respects.

The findings are the work of a team of scientists from the University of Cambridge. They arrived at their conclusions by examining the chemical composition of the Venusian atmosphere.

The team's research, published in the journal Nature Astronomy, could have implications beyond the solar system. The findings could assist astronomers in selecting extrasolar planets or "exoplanets" most likely to be habitable.

"Even though it’s the closest planet to us, Venus is important for exoplanet science because it gives us a unique opportunity to explore a planet that evolved very differently to ours, right at the edge of the habitable zone," team leader Tereza Constantinou, a PhD student at Cambridge’s Institute of Astronomy, said in a statement.

Alternative history Venus

Currently, Venus has a scorching hot surface temperature of around 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit (500 degrees Celsius), hot enough to melt lead.

If that weren't intimidating enough, the second planet from the sun also has clouds of sulfuric acid.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Despite these extreme conditions, many scientists theorize that Venus may have been habitable billions of years ago. Much of the investigation into this question has focused on water, which we understand is the key ingredient for life.

There are two primary concepts of how Venus could have evolved over the last 4.6 billion years.

One idea suggests that the planet was once cool enough to host liquid water. According to this theory, this situation changed due to a runaway greenhouse effect driven by volcanic activity.

As a result, Venus gradually became hotter and hotter, reaching the point at which it could no longer harbor water in a liquid state.

The other theory suggests that Venus never harbored liquid water because the planet was "born hot." The team's results seem to favor this waterless alternative history.

"Both of those theories are based on climate models, but we wanted to take a different approach based on observations of Venus' current atmospheric chemistry," said Constantinou. "To keep the Venusian atmosphere stable, then any chemicals being removed from the atmosphere should also be getting restored to it, since the planet’s interior and exterior are in constant chemical communication with one another."

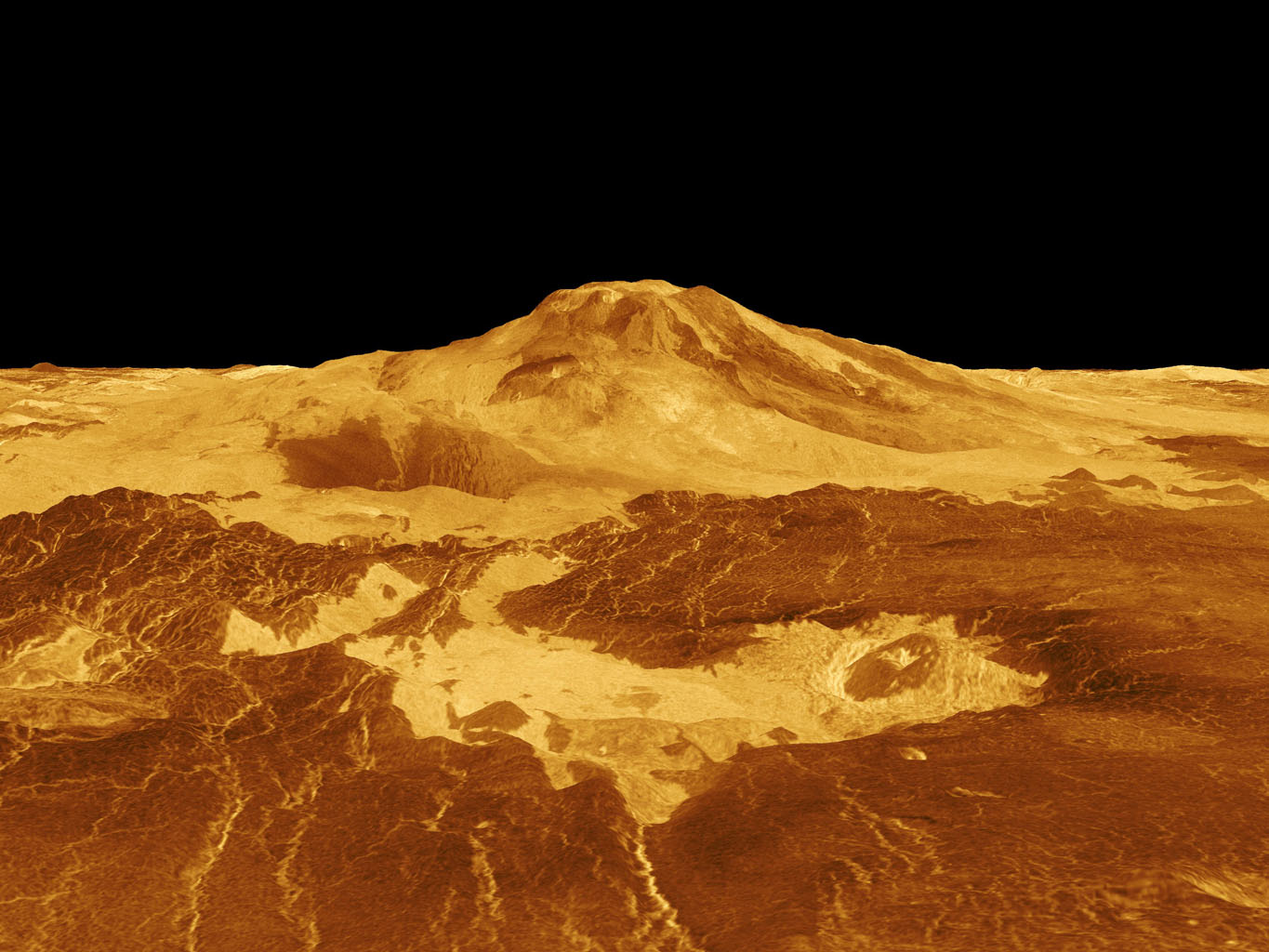

In particular, the researchers looked at how rapidly water, carbon dioxide and carbonyl sulfide are destroyed in the Venusian atmosphere and, thus, how quickly they must be replenished from the planet's interior via volcanism.

By carrying material to the surface of planets to its mantle and releasing it as gas, magma driven by volcanism gives a hint at these world's interiors.

Earth's volcanic eruptions are mostly steam because of our world's water-rich interior. The team discovered that Venus's volcanic gases are, on the other hand, no more than 6% steam.

From these dry eruptions, the researchers inferred that Venus's interior is too dry for the planet to have ever had enough water to supply oceans at its surface.

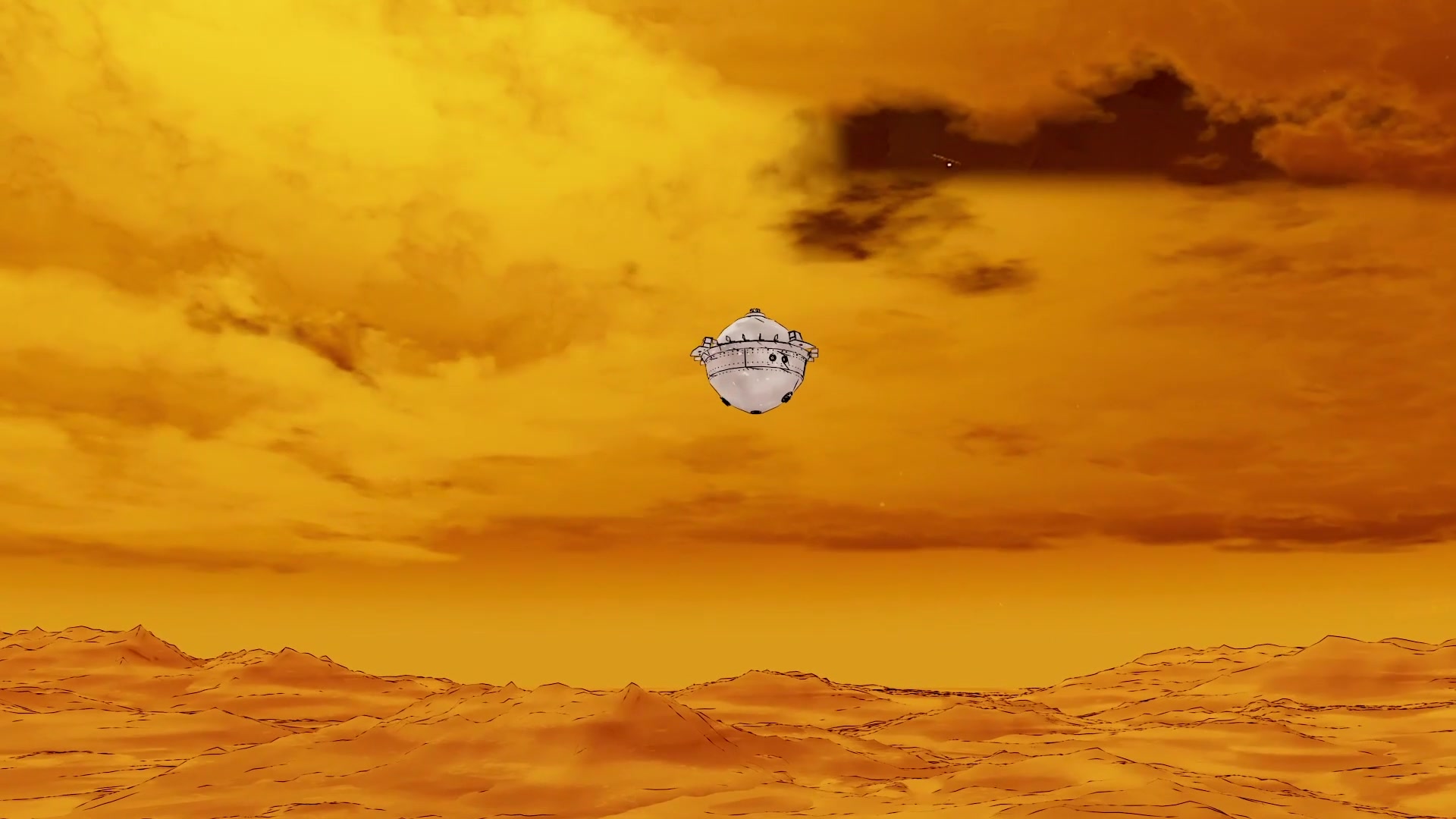

"We won’t know for sure whether Venus can or did support life until we send probes at the end of this decade," Constantinou said. "But given it likely never had oceans, it is hard to imagine Venus ever having supported Earth-like life, which requires liquid water."

Humanity may not have to wait long to answer this question. NASA's DAVINCI mission is currently expected to launch in June 2029, and it will reach Venus two years later.

Once in situ around the hellish planet, DAVINCI will drop a probe through its atmosphere, collecting vital data. Though the probe isn't designed to survive the descent, there is the chance it could catch a 7-second glimpse of the Venusian surface.

Constantinou explained that if Venus was habitable in the past, it would mean exoplanets that we have already discovered could also be habitable.

"Instruments like the James Webb Space Telescope are best at studying the atmospheres of planets close to their host star, like Venus. But if Venus was never habitable, then it makes Venus-like planets elsewhere less likely candidates for habitable conditions or life," Constantinou said.

"We would have loved to find that Venus was once a planet much closer to our own, so it’s kind of sad in a way to find out that it wasn’t, but ultimately, it’s more useful to focus the search on planets that are mostly likely to be able to support life – at least life as we know it."

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. who specializes in science, space, physics, astronomy, astrophysics, cosmology, quantum mechanics and technology. Rob's articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University