How many times has Earth orbited the sun?

We worked out how many trips each of the solar system's eight planets has taken around the sun over the past 4.6 billion years.

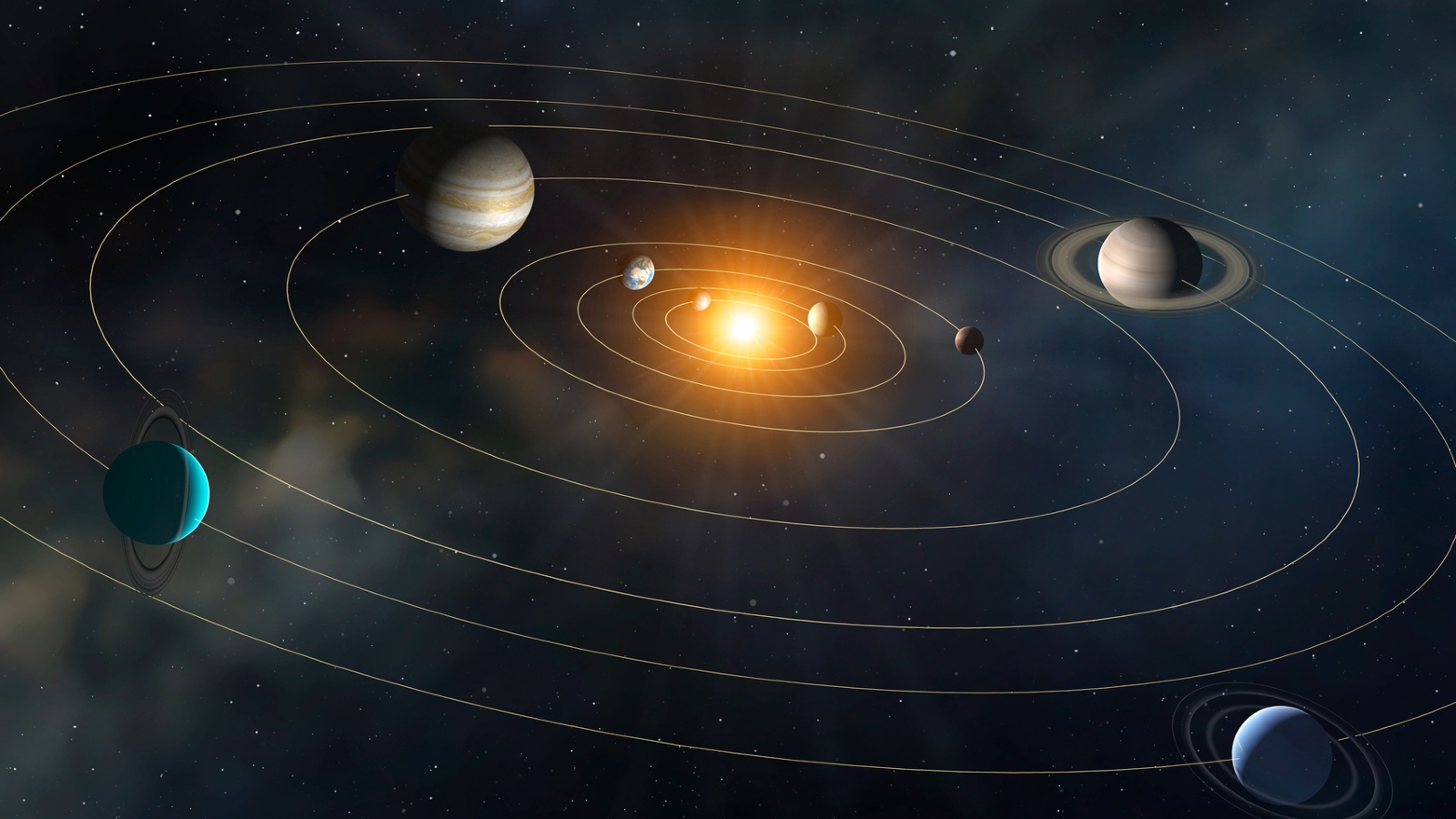

When you're standing on Earth's surface, it's easy to forget that our planet is hurtling around the sun at more than 67,000 mph (107,800 km/h). And it's even easier to forget that there are seven other planets also making their way around our home star at similar breakneck speeds, or that all eight have been ceaselessly circling the solar system for billions of years.

But what might really blow your mind is finding out how many trips around the sun each planet has under its belt. This may seem like a tricky thing to calculate, but because the planets' orbits have remained largely unaltered for most of their existence, all it takes is a bit of basic math.

Related: What's the maximum number of planets that could orbit the sun?

The solar system was born around 4.6 billion years ago, when the sun began to form from a cloud of dust left behind by prior stellar explosions. Around 4.59 billion years ago, the giant planets — Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune — were born. And around 4.5 billion years ago, the smaller, rocky planets — Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars — took shape, according to The Planetary Society.

But when the planets were born, their orbits around the sun were not the same as they are today (especially those of the giant planets). For around 100 million years after the first planets formed, there was a "dynamical instability" among them, which resulted in a gravitational tug-of-war between these large bodies and caused the rest of the outer solar system's planetary material, and even some emerging protoplanets, to be catapulted out of the solar system, Sean Raymond, an astronomer at the Bordeaux Astrophysics Laboratory in France and an expert on planetary systems, told Live Science in an email.

However, once all of the planets had emerged and finished jostling with one another for their positions, they settled into consistent, stable orbits that haven't changed much since.

"For 98% to 99% of the solar system's lifetime, the planets' orbits have been nice and stable," Raymond said. As a result, you can use the planets' current orbital dynamics to make a pretty accurate guess at how many trips they have made around the sun, he added.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Take Earth, for example. Our planet takes a year to orbit the sun and has existed for 4.5 billion years, so it has taken roughly 4.5 billion trips around the solar system.

However, the number of total orbits varies greatly among the other planets because their years are either shorter or longer than Earth's.

Mercury, the closest planet to the sun, takes only 88 days (or roughly 0.24 years, based on a year with 365.25 days) to travel around the sun once. So, over the past 4.5 billion years, it has completed around 18.7 billion solar orbits. But Neptune, the farthest planet from the sun, takes around 60,190 days (or 164.7 years) to complete an orbit, which means it has managed only about 27.9 million trips around the sun during its 4.59 billion years of existence. That means Mercury has orbited the sun around 18.7 billion times more than Neptune has.

Here is the full list of the planets, their year length and their total number of trips around the sun:

| Planet | Age (in billions of years) | Orbital period (in days) | Number of total orbits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury | 4.5 | 88 | 18.7 billion |

| Venus | 4.5 | 225 | 7.3 billion |

| Earth | 4.5 | 365.25 | 4.5 billion |

| Mars | 4.5 | 687 | 2.4 billion |

| Jupiter | 4.59 | 4,333 | 386.9 million |

| Saturn | 4.59 | 10,759 | 155.8 million |

| Uranus | 4.59 | 30.687 | 54.6 million |

| Neptune | 4.59 | 60,190 | 27.9 million |

These sound like impressive numbers (and they are) but most of the planets could potentially double their number of orbits in their remaining lifetimes.

In around 4.5 billion years, the sun will have swollen outward to reach Earth's orbit and transition into a red dwarf star, which will destroy Mercury, Venus and Earth. The other planets may live on for a time if they are not burned up but their orbits will likely be majorly altered.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.