Why is Pluto not considered a planet?

Pluto was demoted from a planet to a dwarf planet in 2006. So why is its status still so controversial today?

When the International Astronomical Union (IAU) demoted Pluto from a planet to a dwarf planet in 2006, it surprised a lot of people, including some scientists. Even many years later, some astronomers want to revise the definition of a planet to clarify the parameters that set planets apart from other celestial objects.

But why isn't Pluto considered a planet anymore? It starts with the definition of a planet — or lack thereof. Before 2006, there weren't strict criteria for a planet. Instead, planets were loosely regarded as objects larger than asteroids that orbited the sun. In the mid-1800s, for example, more than a dozen objects that we now regard as asteroids were considered to be planets.

When did Pluto become a planet?

When Pluto was discovered by Clyde Tombaugh in 1930, scientists were searching far and wide for an unknown celestial body to explain some irregularities in Uranus' orbit. Tombaugh, a newly minted astronomer at Lowell Observatory in Arizona, was tasked with identifying the culprit. After several months, he successfully located a round, rocky object beyond Uranus that he believed might contribute to its orbital wobble. It would eventually be named Pluto after the Roman god of the underworld. Despite being smaller than several known moons, it was deemed large enough to be considered a planet.

However, it soon became apparent that Pluto was not big enough to exert the kind of gravitational pull necessary to influence Uranus' orbit. What's more, in the 1990s, astronomers discovered that Pluto was surrounded by a number of similarly sized objects; it belonged to a region of the solar system later named the Kuiper Belt.

This sparked debate about Pluto's status in the planetary canon, which came to a head at a 2006 meeting in Prague.

Why is Pluto not considered a planet?

That year, the IAU tasked a small committee with creating a working definition of a "planet." They landed on three criteria:

- It must orbit around the sun.

- It must have enough mass to draw itself into a round shape.

- It must have cleared all other celestial bodies, except its own moons, from its orbit.

Based on the third requirement, the committee declared that Pluto no longer qualified as a planet because of its position in the cluttered Kuiper Belt, where thousands of objects sit beyond the orbit of Neptune. Pluto, therefore, is not the gravitationally dominant object in its neighborhood — and thus, not a planet, according to the new definition.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Related: When will Pluto complete its first orbit since its discovery?

But this framework drew immediate criticism. "That definition is clearly inadequate, because it excludes exoplanets," or planets discovered beyond our solar system, Jean-Luc Margot, a planetary scientist at UCLA, told Live Science. It is also extremely difficult to determine when a body has cleared its own orbit, he said — Pluto clearly hasn't, but by some definitions, neither has Mars.

Pluto's demotion remains controversial for some scientists, though, in part because of the way it was reclassified. Philip Metzger, a planetary physicist who worked on NASA's New Horizons mission to Pluto, has previously pointed out that the IAU did not put their definition of a planet up for a vote from the larger scientific community. In his view, that makes the new definition invalid. And for others, it's a matter of sentiment — many people grew up thinking of Pluto as a planet, and they are still emotionally invested in it.

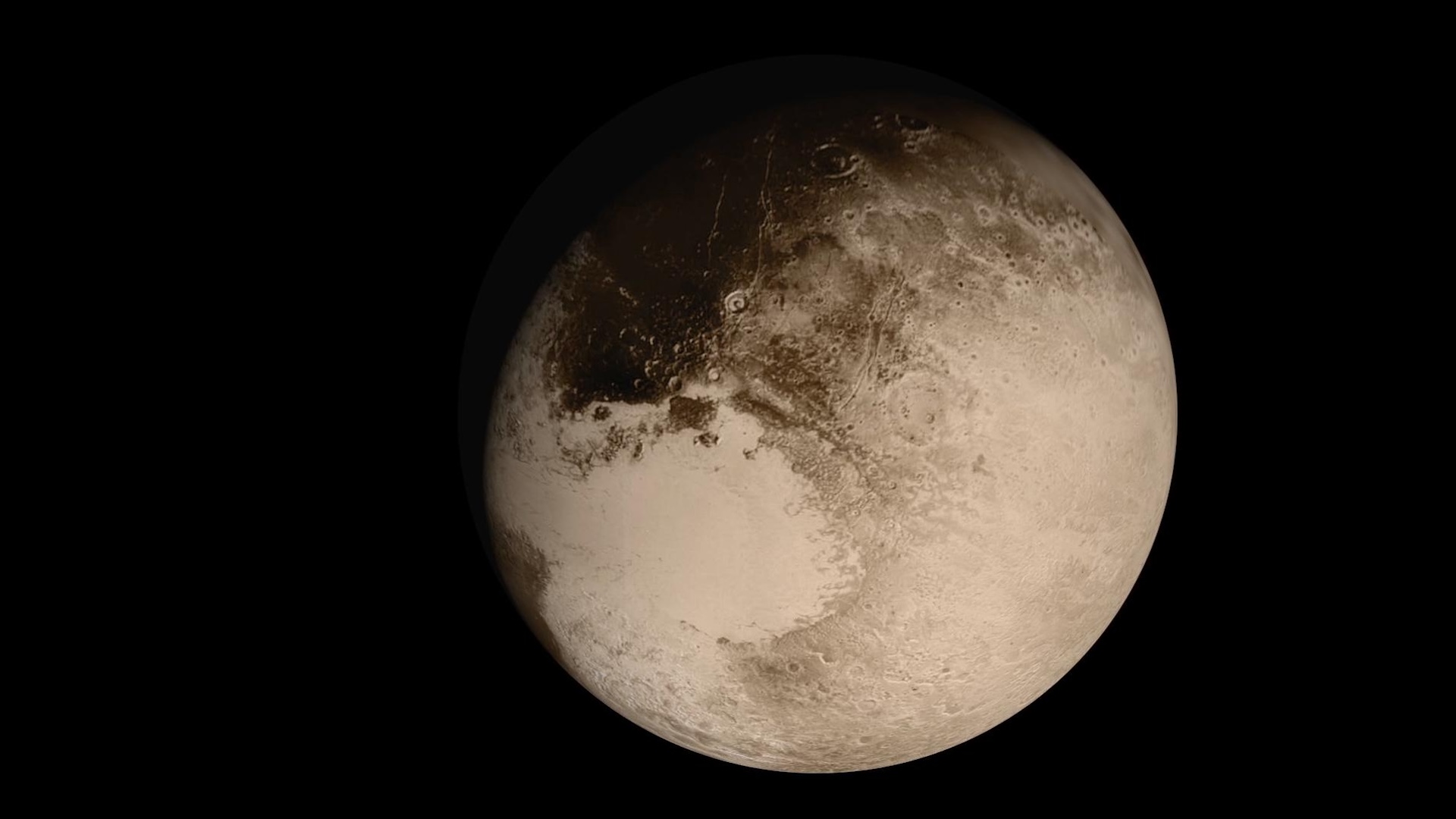

Regardless of whether Pluto is a planet or a dwarf planet, it remains a fascinating part of the solar system, from its huge white "heart" of frozen nitrogen to the ice-spewing 'supervolcano' thought to lurk below its surface.

"Pluto hasn't changed," Margot said. "It's just as exciting."

Joanna Thompson is a science journalist and runner based in New York. She holds a B.S. in Zoology and a B.A. in Creative Writing from North Carolina State University, as well as a Master's in Science Journalism from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. Find more of her work in Scientific American, The Daily Beast, Atlas Obscura or Audubon Magazine.