We might have been completely wrong about the origin of Saturn's rings, new study claims

Computer modeling suggests Saturn's rings are billions of years older than previous research suggests — but the new findings are up for debate.

Saturn's rings could be billions of years old despite not looking a day over a few hundred million, a new study has found.

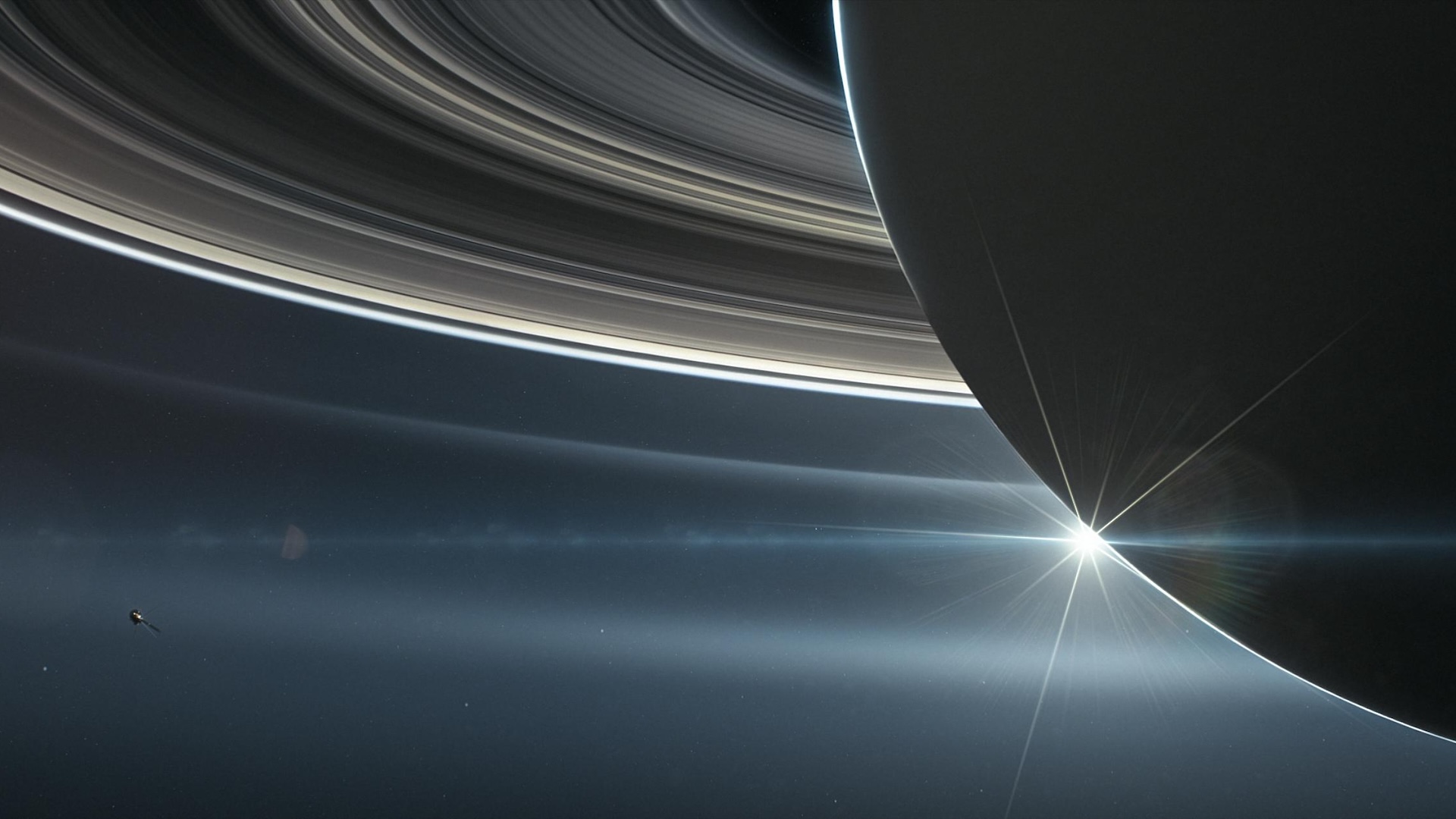

The rings of Saturn are one of our solar system's greatest wonders; made up of billions, if not trillions, of chunks of water ice which can be smaller than a grain of sand and larger than a mountain, according to NASA. However, they're also a bit of an enigma.

Researchers have been debating the origins and age of Saturn's rings for decades. Some scientists argue that the rings formed as recently as 100 million years ago — when dinosaurs still roamed our planet — after Saturn's gravitational pull tore apart a passing comet or icy moon.

One of the reasons scientists believed the rings were so young is that they appear very clean — in the context of planetary rings, this means that the icy chunks from which they are formed haven't been dirtied up by collisions with tiny space rocks called micrometeoroids over billions of years. However, a new study published Dec. 16 in the journal Nature Geoscience suggests that micrometeoroids wouldn't actually stick to the rings, so they may look younger than they really are.

"A clean appearance does not necessarily mean the rings are young," study lead author Ryuki Hyodo, a planetary scientist at the Institute of Science Tokyo, told Live Science's sister site Space.com.

Related: Saturn's moon Titan may have a 6-mile-thick crust of methane ice — could life be under there?

The new study suggests that the rings could have formed early in the solar system's history, around 4.5 billion to 4 billion years ago, when, according to Hyodo, the solar system was a lot more chaotic.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Many large planetary bodies were still migrating and interacting, greatly increasing the chances of a significant event that could have led to the formation of Saturn's rings," he said.

To learn more about the rings, Hyodo's team used computer modeling to run simulations of micrometeoroid strikes. These simulations determined that the micrometeoroids would hit the rings at a high enough speed to be vaporized, reaching a peak temperature of almost 18,000 degrees Fahrenheit (10,000 degrees Celsius), according to the study. In other words, no solid material would be implanted in the rings.

Additional simulations suggested that vapor from the micrometeoroids would expand, cool and then form charged nanoparticles and ions, which would collide with Saturn, escape its gravity or get dragged into the planet's atmosphere. Either way, the rings would be left squeaky clean and retain a relatively youthful appearance.

However, the debate over the age of the rings is likely to continue. Sascha Kempf, an associate professor of physics at the University of Colorado Boulder who led a 2023 study suggesting that Saturn's rings are no older than 400 million years old, isn't convinced by the new findings.

Kempf told the New Scientist that his team used a more complex method for estimating ages that relied on more than just ring pollution efficiency and included the time it takes for material to arrive and disappear.

"We are pretty certain that this is not really telling us that we have to go back to the drawing board," Kempf said.

Lotfi Ben-Jaffel, a researcher at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics in France who wasn't involved in either study, told New Scientist that the new research suggests the rings are older than has been claimed in recent years but added that Hyodo's team still needs to improve their modeling to give a more precise age estimate.

"It represents a positive step toward the missing modeling effort required to properly handle the fundamental problem of the formation and evolution of a planetary ring system," Ben-Jaffel said.

Patrick Pester is the trending news writer at Live Science. His work has appeared on other science websites, such as BBC Science Focus and Scientific American. Patrick retrained as a journalist after spending his early career working in zoos and wildlife conservation. He was awarded the Master's Excellence Scholarship to study at Cardiff University where he completed a master's degree in international journalism. He also has a second master's degree in biodiversity, evolution and conservation in action from Middlesex University London. When he isn't writing news, Patrick investigates the sale of human remains.