Ammonia leak on Russian section of International Space Station 'has now ceased,' but astronauts remain cautious

A toxic coolant leak discovered on Russian space station equipment is only the latest in a series of malfunctions in recent months.

On Wednesday (Oct. 11), a coolant leak on a Russian module of the International Space Station (ISS) appears to have stopped two days after being discovered, NASA wrote in a blog post.

Space station astronauts were "never in any danger" due to the ammonia leak that began on Monday (Oct. 9), NASA officials said. Still, the space agency has postponed two previosuly scheduled spacewalks on Oct. 12 and Oct. 20, while NASA engineers continue to review the situation. (Ammonia is so toxic that spacewalks nearby the substance must have extra precautions built in to reduce exposure risk to astronauts.)

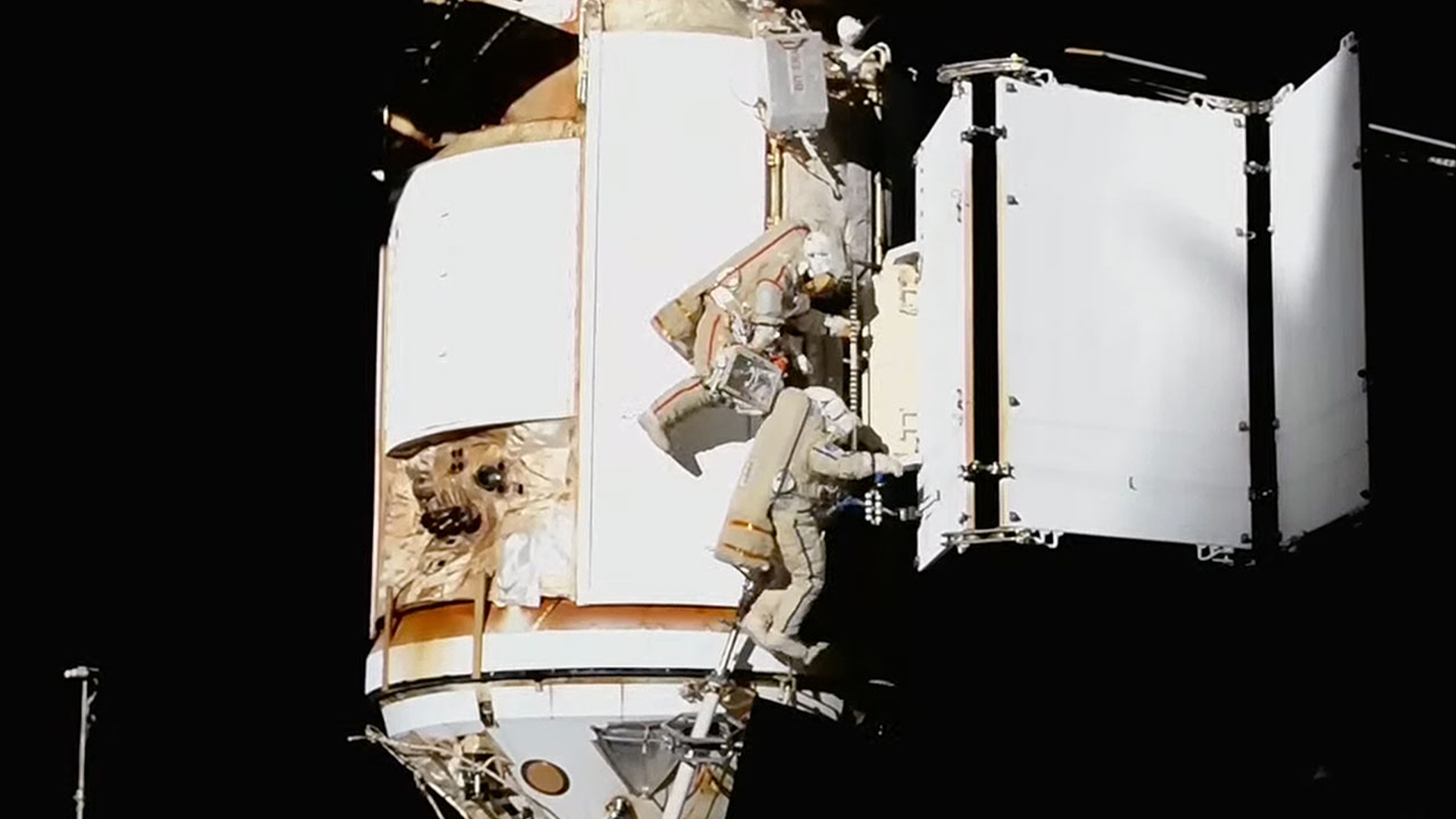

On Monday, toxic ammonia flakes were observed on the International Space Station's (ISS) Russian Nauka Multipurpose Laboratory Module (MLM) around 1 p.m. EDT (1700 GMT). Personnel in NASA's Mission Control in Houston first spotted the "possible" leak on camera.

Agency astronaut Jasmin Moghbeli (on board the ISS) confirmed the backup radiator leak after looking at it through the station's wrap-around cupola windows, NASA officials wrote in an update five hours later.

NASA officials emphasized that the backup radiator leak had "no impacts to the crew or to space station operations," and that the primary radiator for Nauka continues to work normally. NASA officials added the leak, the latest in a series aboard Russian ISS equipment in recent months, remains under investigation.

Russia's federal space agency, Roscosmos, confirmed the leak to NASA and also in a statement on Telegram. "The temperature at the MLM is comfortable," Russian officials wrote on Telegram (translation provided by Google) and they also said there are no changes to operations, experiments or crew exercise periods.

The leaky backup radiator was originally for a different Russian module aboard the space station, called Rassvet, and was delivered to the ISS via space shuttle mission STS-132 in 2010. A Roscosmos spacewalk in April 2023 transferred the then-functional backup radiator to Nauka.

Ammonia is required to cool the ISS because the station's systems produce "waste heat," according to NASA documentation. Waste heat is removed through cold plates (devices that cool electronics) and heat exchangers. Both these device types require circulating ammonia coolant, located in a closed-loop system on the outside of the space station. The warmed ammonia's heat releases into space via radiators, such as the leaky one aboard Nauka, allowing for the liquid's recirculation in the loop for a new round of cooling.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Nauka leak is the latest in a string of ISS Russian equipment coolant escapes in recent months. Roscosmos has said the last two incidents were likely due to micrometeroid impacts, although Harvard-Smithsonian space analyst Jonathan McDowell told The Guardian he suspects there is a "systemic" problem.

"You've got three coolant systems leaking — there's a common thread there. One is whatever, two is a coincidence, three is something systemic," McDowell said in the report. McDowell is an astrophysicist and astronomer who also tracks launches, re-entries and other major spaceflight milestones.

The most dramatic of the two other Russian leaks was a December 2022 incident aboard the Soyuz MS-22 spacecraft, shortly before a scheduled Roscosmos spacewalk; two cosmonauts were in fact already suited up to exit the station just before the leak happened. The extravehicular activity was canceled due to the risk to the cosmonauts.

Roscosmos next examined its options for the spacecraft, then set to carry three astronauts home in early 2023, including American astronaut Frank Rubio, who would inadvertently spend a record-setting 371 consecutive days aboard the ISS due to the Soyuz malfunction. The Russian agency determined it was best to quickly send up an empty replacement Soyuz, MS-23, and return MS-22 back to Earth for analysis.

Soyuz crews typically launch every six months. As such, the relief Soyuz crew wasn't fully trained yet for the accelerated MS-23 launch in February 2023, necessitating a wait until yet another spacecraft (MS-24) was ready in September to carry them to the ISS.

After the relief crew arrived, the three MS-22/MS-23 astronauts then returned home in the replacement spacecraft, having been required to spend 12 months on the ISS instead of six to accommodate the spacecraft changeover. In the meantime, a Russian cargo spacecraft (Progress 82) also sprung an ammonia leak in February 2023.

There have been other incidents with Russian ISS equipment in recent years. Faulty software aboard Nauka when it first docked with the ISS in July 2021, for example, briefly tilted the space station and caused NASA's Mission Control to declare an emergency, although the crew was never in any danger and the situation was swiftly and safely rectified.

And another Russian Soyuz spacecraft docked with the orbiting complex in 2018 somehow ended up with a hole, which was plugged by orbiting astronauts before the spacecraft safely returned home. The cause may have been a manufacturing defect, although reports also emerged in 2021 that Roscosmos was trying to blame U.S. astronauts for the situation.

Tensions erupted between Russia and most of the other ISS partners in February 2022 following Russia's unsanctioned invasion of Ukraine that year, which is ongoing. Relations regarding the ISS have been normal, NASA officials continue to emphasize, but most other space partnerships between Russia and other ISS partners have been severed amid the war. The ISS is scheduled to continue operations until at least 2030, although Russia has only committed to 2028 so far.

Originally posted on Space.com. This article was updated on Oct. 11 by Live Science.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.