Falling metal space junk is changing Earth's upper atmosphere in ways we don't fully understand

A research plane that flew through Earth's stratosphere identified more than 20 elements that are linked to the aerospace industry. Experts predict that the problem could become much worse in the future.

The sky is littered with metal pollution from bits of space junk that burn up as they reenter the atmosphere, a new study reveals. This unexpected level of contamination, which will likely rise sharply in the coming decades, could change our planet's atmosphere in ways we still don't fully understand, researchers warn.

The study, published Oct. 16 in the journal PNAS, is part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) Stratospheric Aerosol Processes, Budget and Radiative Effects (SABRE) mission, which monitors the levels of aerosols — tiny particles suspended in the air — within the atmosphere.

The team used a research plane, which was fitted with a specialized funnel on its nose cone that captures and analyzes aerosols to sample the stratosphere — the atmosphere's second layer that spans between 7.5 and 31 miles (12 and 50 kilometers) above the planet's surface. The study was designed to detect aerosols covered with "meteor dust" left behind by space rocks that burned up upon entry. Instead, the plane detected high levels of metallic elements contaminating the floating molecules, none of which could be explained by meteors or other natural processes.

The two most surprising elements were niobium and hafnium, which are both rare earth metals used to make technological components such as batteries. The researchers were also puzzled by high levels of aluminum, copper and lithium.

The team had not expected to find these elements in the stratosphere and were initially confused as to where they had come from, study lead author Daniel Murphy, an atmospheric chemist at NOAA's Chemical Sciences Laboratory in Boulder, Colorado, said in a statement. "But the combination of aluminum and copper, plus niobium and hafnium, which are used in heat-resistant, high-performance alloys, pointed us to the aerospace industry," he said.

Related: 15 of the weirdest things we have launched into space

The discovery "represents the first time that stratospheric pollution has been unquestionably linked to reentry of space debris," researchers wrote in the statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In total, the study identified 20 different metallic elements that do not naturally occur in Earth's atmosphere, including silver, iron, lead, magnesium, titanium, beryllium, chromium, nickel and zinc.

The team suspects that the main source of the pollution is rocket boosters that are ejected by rockets shortly after they clear the upper atmosphere, then fall back to Earth.

China, which was previously criticized for a series of uncontrolled reentries, is responsible for many of these rocket booster reentries. However, this problem has also plagued Russia and NASA.

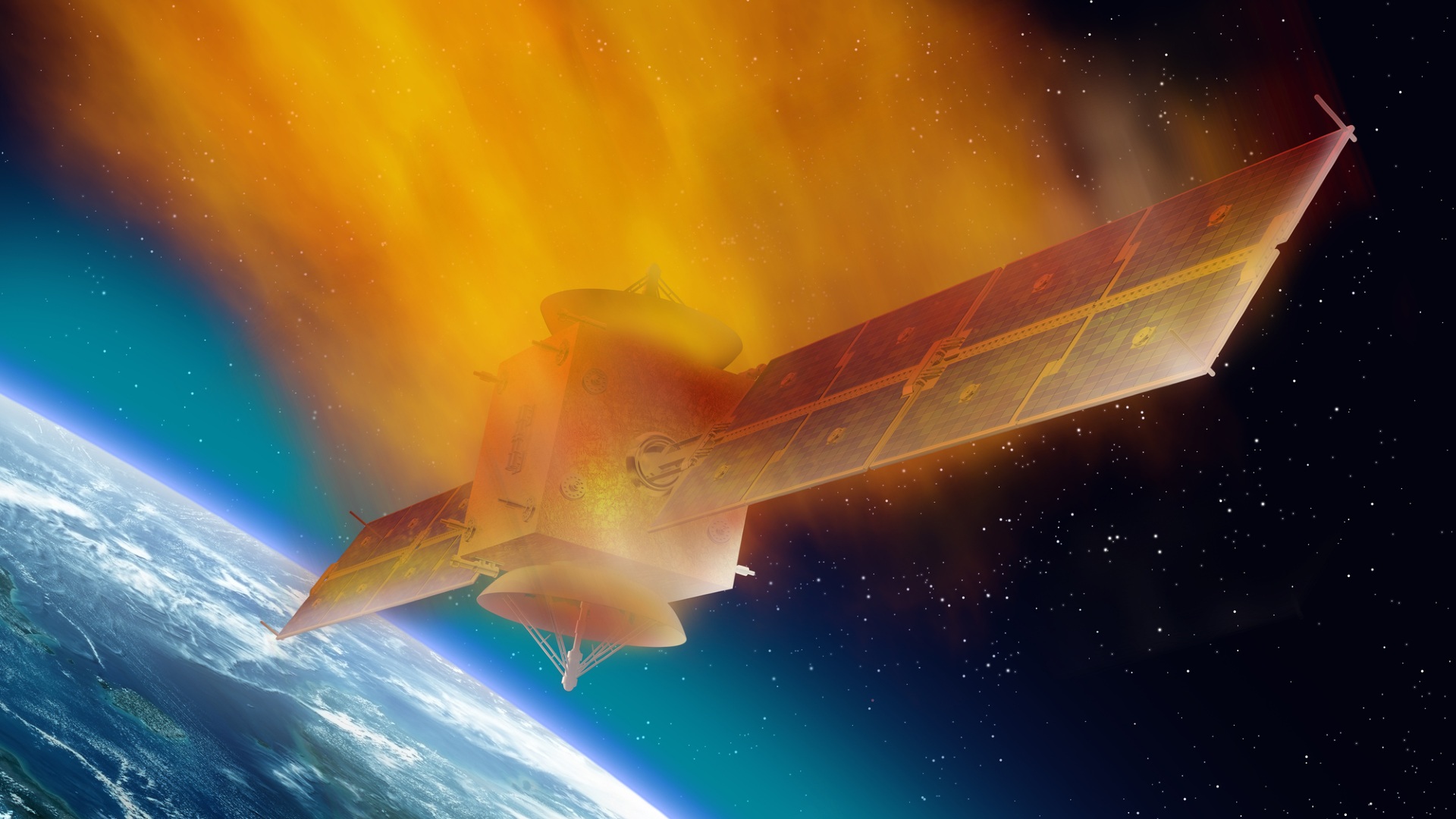

Falling satellites that have been abandoned, knocked out of orbit by solar storms or purposefully crashed back to Earth are also likely to release large amounts of metal pollution as they burn up.

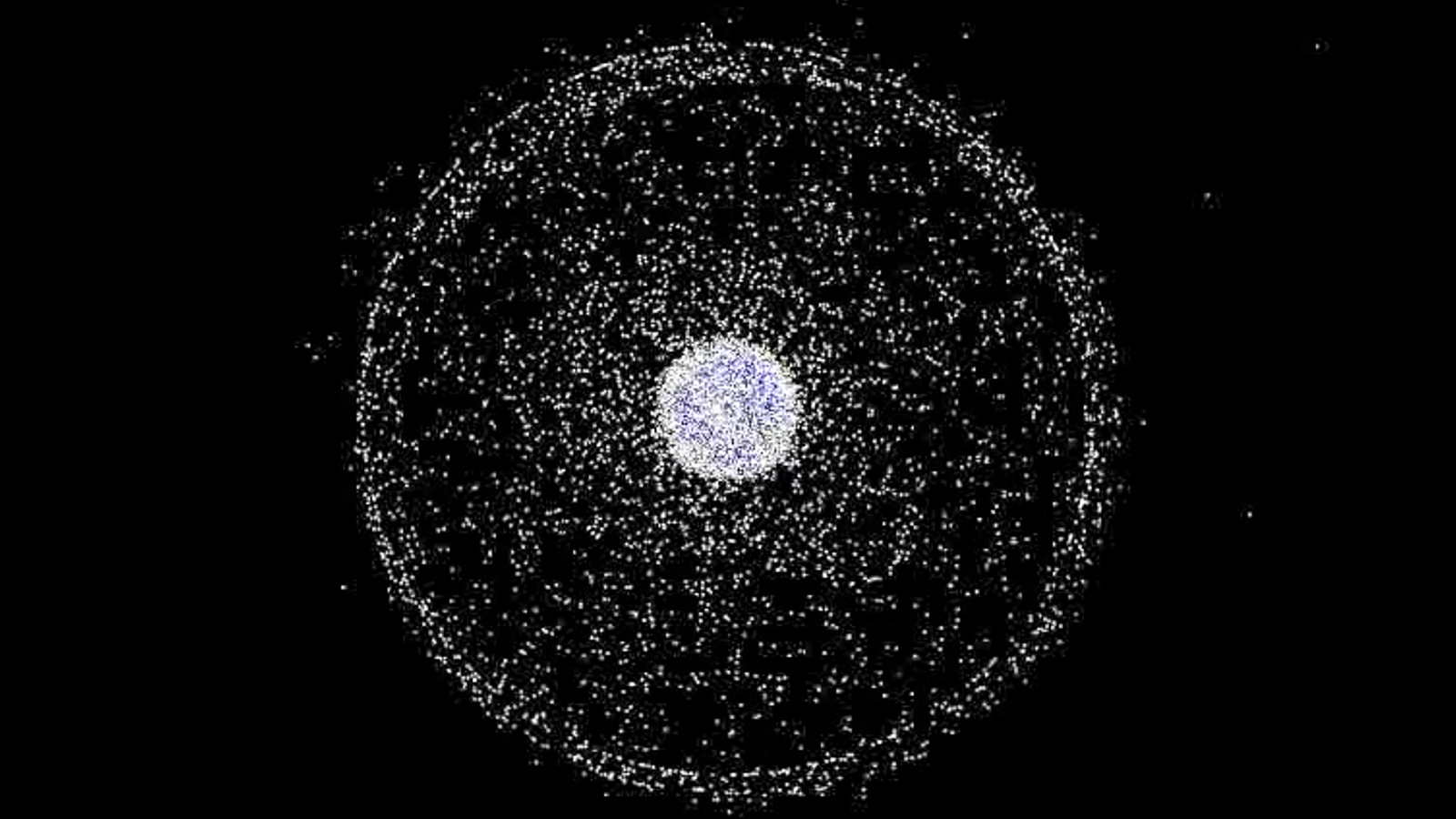

Pollution from satellites will likely increase as more commercial satellites are launched into space. Of particular concern is the nearly 9,000 satellites that are currently in low-Earth orbit, which are all destined to eventually fall back to Earth, according to Orbiting Now.

In total, around 10% of aerosols from the new study were polluted with space junk metals. But the researchers predict that this could jump to around 50% in the next few decades.

It is currently too early to tell what long-term effects this pollution will have on our planet. But past atmospheric pollution, such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), contributed to holes in the ozone layer. Aerosols also play a role in reflecting sunlight back into space, which is important for mitigating the effects of climate change.

"A lot of work" will be needed to "understand the implications" of these metals in the atmosphere, Murphy said.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.