'Lost in insignificance': Here's what it's like to rappel into the solar system's largest canyon

"You wanted this moment to belong just to yourself and the landscape: sunset on the rim of Valles Marineris, the largest canyon in the solar system."

Have you ever wondered what it would be like to spend a night on Mars? This excerpt from the new book "Daydreaming in the Solar System" by John E. Moores and Jesse Rogerson, takes a poetic look at what it might be like to explore the Red Planet if you were faced with the daunting prospect of climbing the biggest canyon in our solar system.

The book itself features beautiful illustrations by Michelle D. Parsons, and covers everything, from golfing on the moon to visiting Pluto, and is filled with fascinating facts about our small portion of the Milky Way.

Rappelling into Valles Marineris on Mars

You left your vehicle behind at midday so that you could hike far enough in daylight that it would be over the horizon from your perspective by the time you made camp. Why make the coming descent harder than it needs to be? Quite simply, you wanted this moment to belong just to yourself and the landscape: sunset on the rim of Valles Marineris, the largest canyon in the solar system.

And what a moment it is.

You dangle your feet over the edge of this spur into the Coprates section of Marineris and drink in the view as the sun descends into the canyon on this balmy austral summer's day. From your perspective, the floor of the canyon is almost 10 kilometers (6 miles) beneath you. Across the way, from your perspective and nearly 100 km (60 miles) distant from you, the wall of the other side of the canyon rises up again to your level, smoky through the suspended dust.

Related: 32 things on Mars that look like they shouldn't be there

That far wall isn't even the other side of this massive gorge; instead, it's just a finger of land called the Coprates mountains protruding into the center of the great gap. There's a whole other tributary of Marineris on the other side, hidden from view around the curve of the planet. At its widest, Marineris is nearly 600 km (370 miles) across.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As a result, not only is the scale of Marineris difficult to hold in your mind, but you also literally cannot appreciate its entire extent from any point on the surface. Generously, Mars holds back and presents only what you can comprehend. Each view is a frame in a movie that evolves as you travel the nearly 4,000-km (2,500 miles) length of this feature from Noctis Labyrinthus in the west to the Aurorae Chaos in the east. You take a moment to consider that this distance is farther than the distance between the surface and the center of the planet.

By contrast, the Earth's Grand Canyon is a mere 29 km (18 miles) wide and only about 2 km (1 mile) deep, extending for less than 500 km (300 miles). A sight to make a human feel small, certainly, but a feature that would be lost in insignificance on Mars. Marineris alone could enclose hundreds of times the volume.

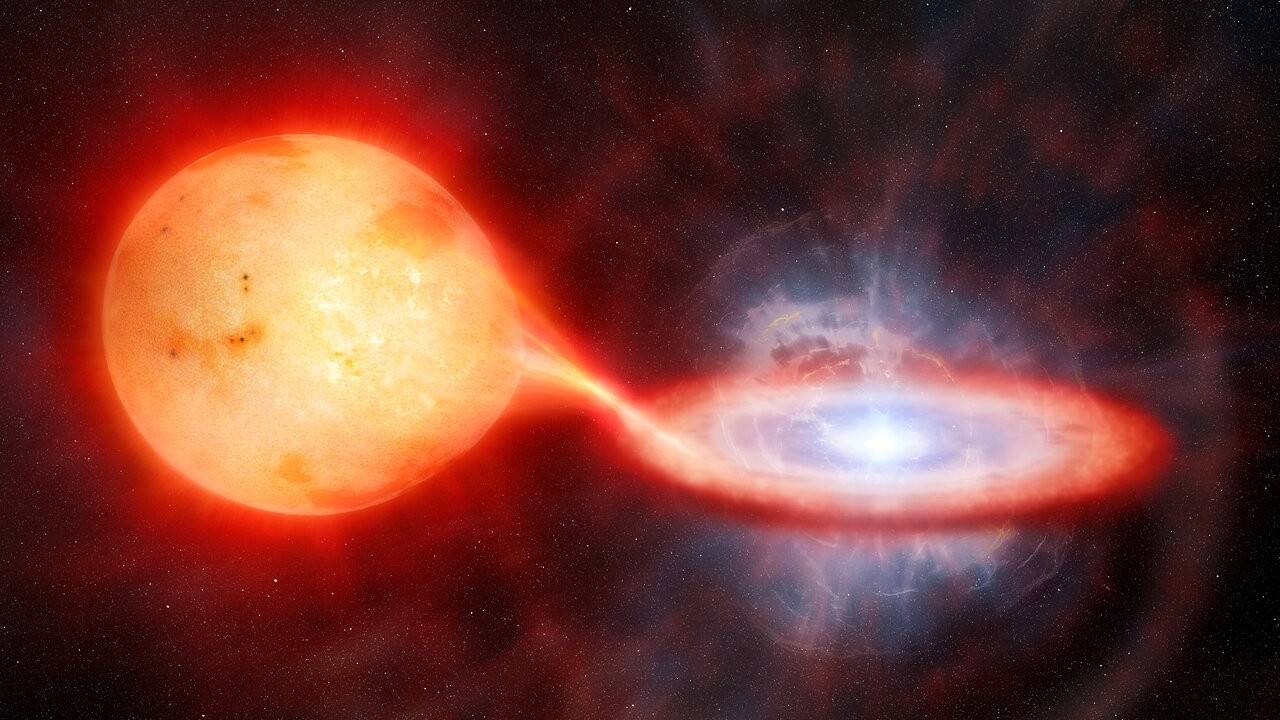

The sky darkens and shifts to cold hues in the long light. Though it looks pure white in photographs because of the exposure time, to human eyes the solar disk itself turns a blue-white — you are looking through so much of the atmosphere at this angle that it is as if the sun has been exsanguinated. On Earth, volcanic ash turns sunsets to a deep red color, scattering away the blue light. But Mars's dust is different, and the particles here combine to scatter away the sun's red light into the rest of the sky, bleeding the sun dry just before the day ends. On especially dusty days, the sun is lost entirely even before it reaches the horizon, dissolving slowly into a thick haze.

Slowly, the stars come out and the vault of the heavens is revealed. But on Mars there is an interloper. A bright evening double star appears in the west, following the sun. It's the Earth and moon. Before coming to Mars, you wondered whether you would be able to see both together or whether they would be blended into a single bright point. Now you realize it's easy to pick them apart. When Mars is closest to the Earth, they can be separated in the sky by more than a quarter of a degree, or about half the width of the full Moon as seen from the Earth.

Of course, Earth gets the better of this arrangement. Someone back at home would observe spectacular views of the fully lit hemisphere of Mars during these oppositions. But from Mars, both the Earth and Moon would appear as thin crescents quite near to the sun in the sky as they followed that copper coin through the daytime. That geometry makes it much harder for a casual Martian observer to get a good view unless they have some effective sunglasses or can time their observing right near either sunrise or sunset, when the bulk of the planet blots out the sun and if the atmosphere is relatively clear of dust.

Turning your eyes from the sky, you start going through your gear in anticipation of the next day. You lay out everything and test it. By and large, it is a typical climber's kit — something recognizable to even ancient mountaineers on Earth. You have ropes and mechanical ascenders, pitons, and other paraphernalia, even an ice ax and ice screws in case the materials of the cliff face change on your way down.

But there are a few tweaks to make these tools more appropriate to Mars. For one, all the equipment seems surprisingly slender and light — the advantages of working in the one third gee on this planet. Additionally, your rope is equipped with an electrostatic clasp. In this way, you can recover your own rope after you have rappelled down a course. That saves you from having to bring too much weight along with you. Indeed, the whole kit fits neatly in a large climbing pack.

As you lay down for the night, you go over the route in your mind. The first course is steep until you get to a ridgeline. You can then follow the ridgeline to two false peaks before the terrain falls away steeply near the bottom. Right where the slope ends, there is a small unnamed crater that you can use to guide your pathway. All told, it's just over 9 km down in a little over 20 km as the crow flies. With an average slope of just a bit over 20 degrees, there will be a combination of nearly walkable slopes and sheer cliffs.

This part of Coprates is as steep as the cliffs that encircle Olympus Mons, but considerably higher. When you throw in the weaker gravity with such colossal ascents, Mars is clearly a climber's paradise. Plus, going down is much faster than going up. Where it might take up to a couple of months to climb this wall of rock, you anticipate getting down in no more than three days. It's for this reason that you have foregone a pressure tent. That will help you to move quickly, light upon the land. But you anticipate that you will look forward to a shower and a stretch with increasing anticipation as you descend.

You smile as you close your eyes. Your last thought before drifting off is that it must look strange to see a person lying on the ground on their back in the middle of the night. Anyone who came upon the scene might be tempted to ask what misfortune you encountered. But, in a spacesuit, you're effectively wearing your own tent — so why not lie down on the regolith and sleep under the stars?

Excerpted from "Daydreaming in the Solar System: Surfing Saturn's Rings, Golfing on the Moon, and Other Adventures in Space Exploration." Copyright © 2024 by John E. Moores and Jesse Rogerson.

"Daydreaming in the Solar System: Surfing Saturn's Rings, Golfing on the Moon, and Other Adventures in Space Exploration" by science communicators and professors John E. Moores and Jesse Rogerson takes the reader on a journey through the far reaches of the solar system.

John E. Moores is a planetary scientist, author and an associate professor at York University in the Centre for Research in Earth and Space Science.

- Alexander McNamaraEditor-in-Chief, Live Science