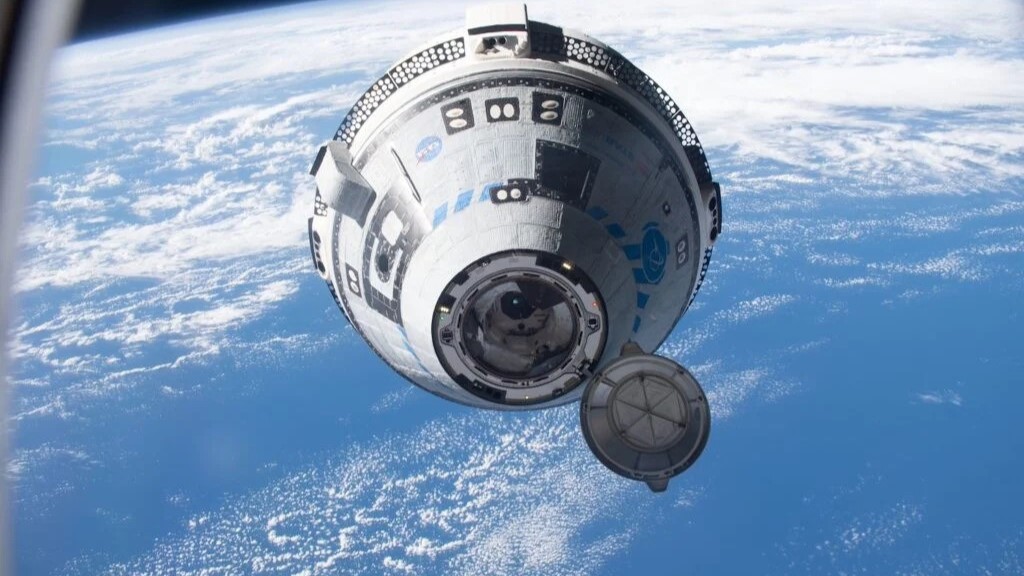

NASA delays Boeing Starliner return flight again amid 'major discussion' about astronaut safety

NASA has once again pushed back the deadline for when the troubled Boeing Starliner spacecraft must leave the International Space Station. The agency expects to be ready to conduct a flight readiness review as soon as the end of next week.

NASA has pushed back the decision to return its stranded Starliner astronauts to the end of August pending a "major discussion" about the spaceship's flight readiness, agency officials have said.

Originally planned to last just 8 days, numerous leaks and other technical issues suffered by Boeing's Starliner spacecraft on its way to the International Space Station (ISS) in June delayed the planned return flight by more than two months, and left its two astronauts — Butch Wilmore and Sunita Williams — stuck in space.

As engineers continue to collect and debate test results on the craft's problems, NASA bosses are still mulling over whether to return the two astronauts on Starliner, or take them back on a SpaceX Dragon capsule six months later instead.

"It's a fairly major discussion to decide whether or not we're going to have crew on board for Starliner's return." Ken Bowersox, associate administrator for NASA's Space Operations Mission Directorate, said at a news conference Wednesday (August 14). "We're expecting that the data analysis will be ready for a program board by the middle to end of next week, and will be ready for a flight readiness review around the end of next week."

Boeing built the Starliner capsule as a part of NASA's Commercial Crew Program, a partnership between the agency and private companies to ferry astronauts into low Earth orbit following the retirement of NASA's space shuttles in 2011.

Starliner blasted off on its inaugural crewed test flight from Florida's Cape Canaveral Space Force Station on June 5. But not long after entering orbit, a number of faults appeared — including five helium leaks and five failures of its reaction control system (RCS) thrusters.

This forced engineers to troubleshoot issues from the ground. Tests conducted at Starliner's facility in White Sands, New Mexico, revealed that during the spacecraft's climb to the ISS, the teflon seals inside the five faulty RCS thrusters likely got hot and bulged out of place to obstruct the propellant flow, according to NASA.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A hotfire test conducted while the craft was docked to the ISS on July 27 showed the thrust was normal, but NASA engineers are concerned the earlier thruster problems could reappear during the craft's descent back to Earth. They are also worried that the helium leaks could knock out some of the craft's orbital maneuvering and attitude control system (OMAC) thrusters, which maintain the spacecraft on its flight path.

"The worst case would be some integrated failure mechanism, between the helium leaks and the RCS thrusters," Steve Stich, the program manager for NASA's Commercial Crew Program, said at a previous news conference on Aug. 7. "Then you could end up in some cases that aren't as easily controlled — more stressing cases that the team is worried about."

NASA's leading contingency plan is to bring the astronauts home aboard a SpaceX Dragon capsule instead. The vehicle will be sent to the ISS as early as Sept. 24 carrying members of the ISS's Crew-9, who will take over from the current Crew-8 aboard the space station. Instead of Crew-9's usual four person crew, two astronauts will go to the ISS to leave space for Wilmore and Williams to return in February 2025.

"I do want to keep this in perspective, if Butch and Suni do not come home on Starliner, they will have about 8 months in orbit," Russ DeLoach, NASA's chief of safety and mission assurance, said at the Aug. 14 news conference.

Yet despite Starliner's problems, NASA said that its astronauts are safe and comfortable aboard the ISS.

"This mission was a test flight... they knew this mission might not be perfect," Joe Acaba, NASA's chief astronaut, said at the press conference. "Human space flight is inherently risky, and as astronauts, we accept that as part of the job."

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.