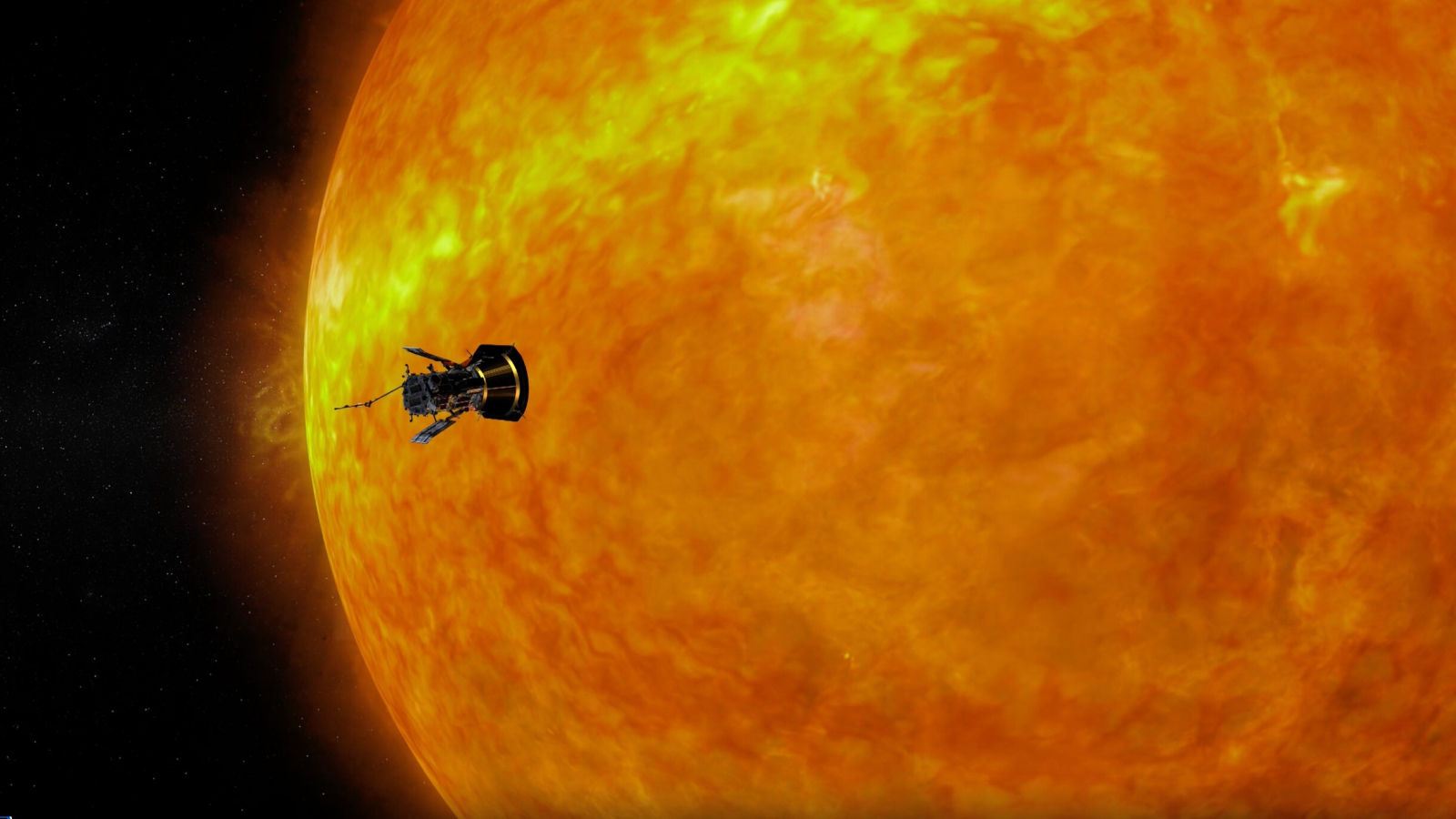

Parker Solar Probe survives historic closest-ever flyby of the sun, NASA confirms

On Christmas Eve, NASA's Parker Solar Probe flew closer to the sun than any human-made object ever — a stunning technological feat that scientists liken to the historic Apollo moon landing in 1969. Now, we know it survived.

Editor's Note: This story was originally published Dec. 24 and updated Friday, Dec. 27 at 10:45 a.m. EST to confirm that the Parker Solar Probe had survived its latest rendezvous with the sun.

NASA's Parker Solar Probe has survived its history-making attempt to fly closer to the sun than we have ever been before — a stunning technological feat that scientists liken to the historic Apollo moon landing in 1969. The record-breaking probe sent a beacon tone back to Earth around midnight EST on Thursday (Dec. 26), a key sign the probe is working normally, NASA announced.

At 6:53 a.m. ET on Tuesday (Dec. 24), the car-sized spacecraft zoomed to within 3.8 million miles (6.1 million kilometers) of the sun's surface, nearly 10 times closer than Mercury's orbit around the star. The probe was likely traveling at an incredible speed of 430,000 mph (690,000 kph) — fast enough to travel from Tokyo to Washington, D.C. in less than a minute — breaking its own record as the fastest human-made object in history.

"Right now, Parker Solar Probe has achieved what we designed the mission for," Nicola Fox, the associate administrator for NASA Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C., said in a NASA video released on Dec. 24. "It's just a total 'Yay! We did it' moment."

Mission control could not communicate with the probe during the closest portion of its rendezvous with the sun, and so scientists s at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland were waiting anxiously for the beacon signal to confirm the spacecraft's survival.

Detailed telemetry data won't come back online till Jan. 1, 2025, NASA announced. Images gathered during the flyby will beam home in early January, followed by scientific data later in the month when the probe swoops further away from the sun, Nour Rawafi, who is the project scientist for the mission, told reporters at the Annual Meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU) earlier this month.

Related: 10 supercharged solar storms that blew us away in 2024

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We can't wait to receive that first status update from the spacecraft and start receiving the science data in the coming weeks," Arik Posner, the program scientist for the Parker Solar Probe at NASA Headquarters, said in a statement.

"No human-made object has ever passed this close to a star, so Parker will truly be returning data from uncharted territory," added Nick Pinkine, the Parker Solar Probe mission operations manager at the Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland.

HAPPENING RIGHT NOW: NASA’s Parker Solar Probe is making its closest-ever approach to the Sun! 🛰️ ☀️ More on this historic moment from @NASAScienceAA Nicola Fox 👇 Follow Parker’s journey: https://t.co/MtDPCEK6w6#3point8 pic.twitter.com/Bq85XFa1QSDecember 24, 2024

Parker launched in 2018 to help decode some of the biggest mysteries about our sun, such as why its outermost layer, the corona, heats up as it moves further from the sun's surface, and what processes accelerate charged particles to near-light speeds. In addition to revolutionizing our understanding about the sun, the probe also caught rare closeups of passing comets and studied the surface of Venus.

On Christmas Eve, the probe flew through plumes of plasma still attached to the sun, where it observed solar flares occurring simultaneously due to ramped-up turbulence on the sun's surface. The spectacular flares can spark breathtaking auroras on Earth but also disrupt communication systems and other technology.

"The sun is doing different things than it did when we first launched," Nicholeen Viall, who is a co-investigator for the WISPR instrument onboard Parker Solar Probe, told reporters at the AGU meeting. "That is really cool because it is making different types of solar winds and solar storms."

Parker's 4.5-inch-thick heat shield is designed to endure temperatures of up to 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit (1,371 degrees Celsius), partly thanks to a specially-designed white coating that will reflect much of the sun's heat and help maintain spacecraft instruments at a comfortable room temperature.

But scientists expected that during this flyby, Parker experienced lower temperatures of about 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit (982 degrees Celsius), Elizabeth Congdon, the lead engineer for the probe's thermal protection system, told reporters at AGU.

"It's really great to see all the science that is enabled by the fact that we overprepared."

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Space.com, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social