Peregrine moon lander carrying human remains doomed after 'critical loss' of propellant

Just six hours into its maiden flight, Astrobotic Technology's Peregrine moon lander has experienced a technical fault that doomed the mission.

Editor's note: Astrobiotic announced on Wednesday (Jan. 10) that they have now found a possible cause for the anomaly that prevented the Peregrine mission from reaching the moon.

The first U.S. spacecraft to attempt a soft landing on the moon in more than 50 years has experienced a "critical loss of propellant," dooming its mission.

The Peregrine spacecraft, owned by the private American company Astrobotic Technology, launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida, aboard a Vulcan rocket at 2:18 a.m. EST (0718 GMT) yesterday (Jan. 8).

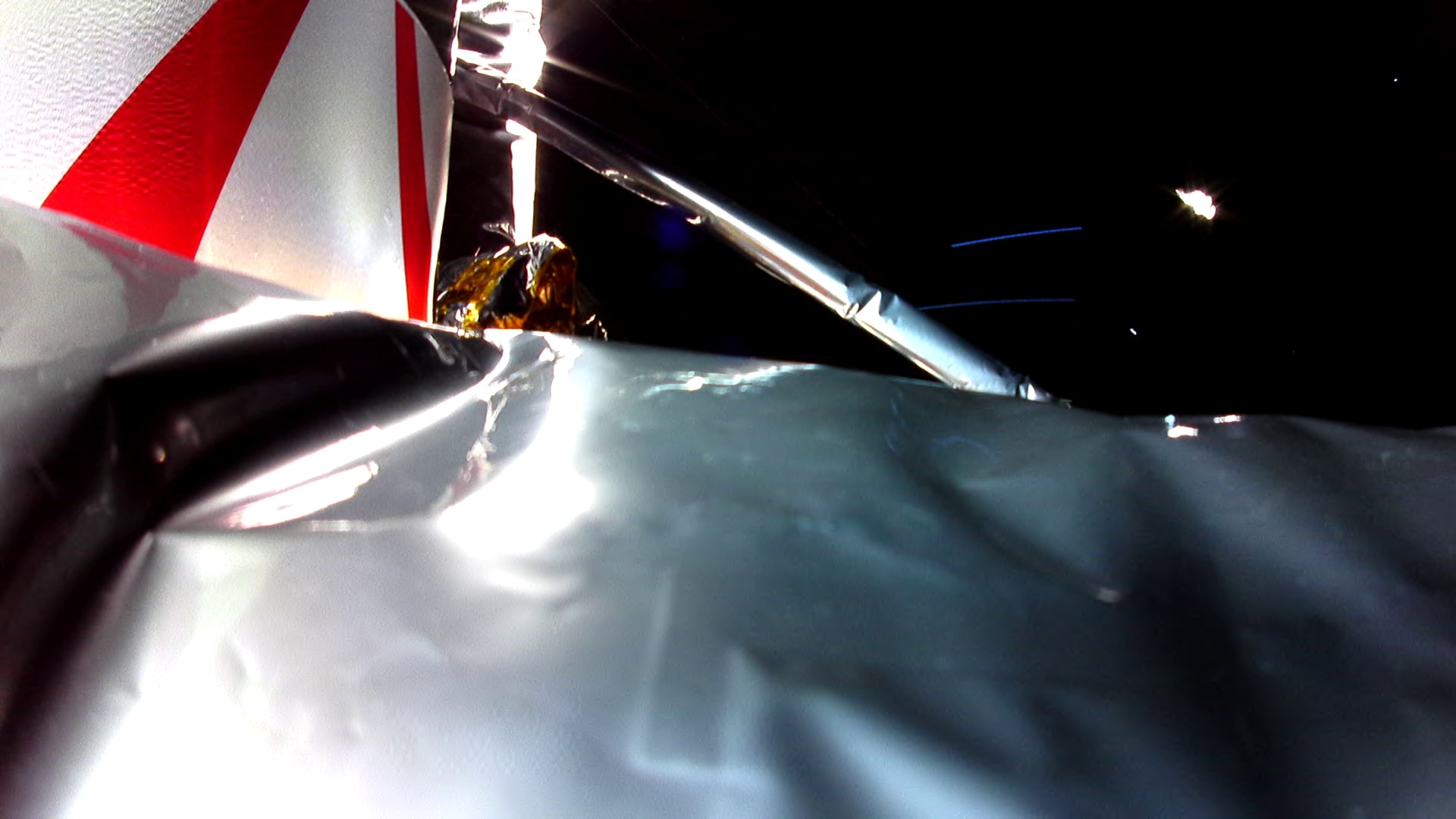

Yet just six hours into the flight, the private moon mission experienced technical difficulties that prevented the Peregrine spacecraft from turning its solar panels toward the sun. As Peregrine's battery dwindled, engineers found a fix that enabled them to tilt the craft and charge the panels.

But a fourth update from the team delivered dire news: The spacecraft had sprung a leak, causing it to lose the necessary rocket fuel for a moon landing.

Related: Human remains on private Vulcan lunar lander will 'desecrate' the moon, Navajo Nation says

"Unfortunately, it appears the failure within the propulsion system is causing a critical loss of propellant," Astrobotic representatives wrote in a statement. "The team is working to try and stabilize this loss, but given the situation, we have prioritized maximizing the science and data we can capture."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The fault has scuppered the first U.S. effort since 1972 — and the first-ever commercial flight to the moon — to attempt a safe landing on the lunar surface. It also means that its payload containing the remains of multiple "Star Trek" cast members and the DNA of former U.S. presidents will be lost in space.

To land on the moon, the 1.3-ton (1.2 metric tons) spacecraft would have needed to reorient its engine to fire in controlled bursts during its descent. Peregrine was set to take a looping path to its final landing spot, and was initially slated for an attempted touchdown on Feb. 23. The lander was intended to deploy five NASA payloads (costing the space agency $108 million for their delivery) and 15 other experiments on the moon.

The instruments — which include devices to measure radiation levels, surface ice and magnetic fields — were built to collect data on the moon's resources and potential risks to human habitation.

Controversially, the spacecraft is also carrying human remains, including those of science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke; Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry; Roddenberry's wife, Majel Barrett; and Nichelle Nichols, James Doohan and DeForest Kelley, who played Nyota Uhura, Montgomery Scott and Dr. Leonard McCoy, respectively, on the classic sci-fi show. Stored alongside these remains are samples of DNA of the U.S. presidents George Washington, Dwight Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, and Ronald Reagan.

But with only 40 hours of thruster fuel remaining on the spacecraft, Astrobotic's updated goal is to get the lander as close to the moon as possible.

"At this time, the goal is to get Peregrine as close to lunar distance as we can before it loses the ability to maintain its sun-pointing position and subsequently loses power," Astrobotic representatives said.

Astrobotic is the first of three U.S. companies to send a lander to the moon this year. Along with the companies Intuitive Machines and Firefly Aerospace, it has entered a new private-public partnership with NASA that will send five more missions to our lunar companion in 2024.

The partnership sees NASA acting as a "customer," taking a back seat to the companies on spacecraft design and mission planning — an arrangement that the space agency says will cut costs, boost development speed and encourage innovation. As such, NASA has said it can tolerate some failures, yet the loss of the mission is still significant.

"We will incentivize speed, financially," Thomas Zurbuchen, then associate administrator of NASA's Science Mission Directorate, said at a news conference in 2019.

"We want to start taking shots on goal," Zurbuchen said in an interview in 2022.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.