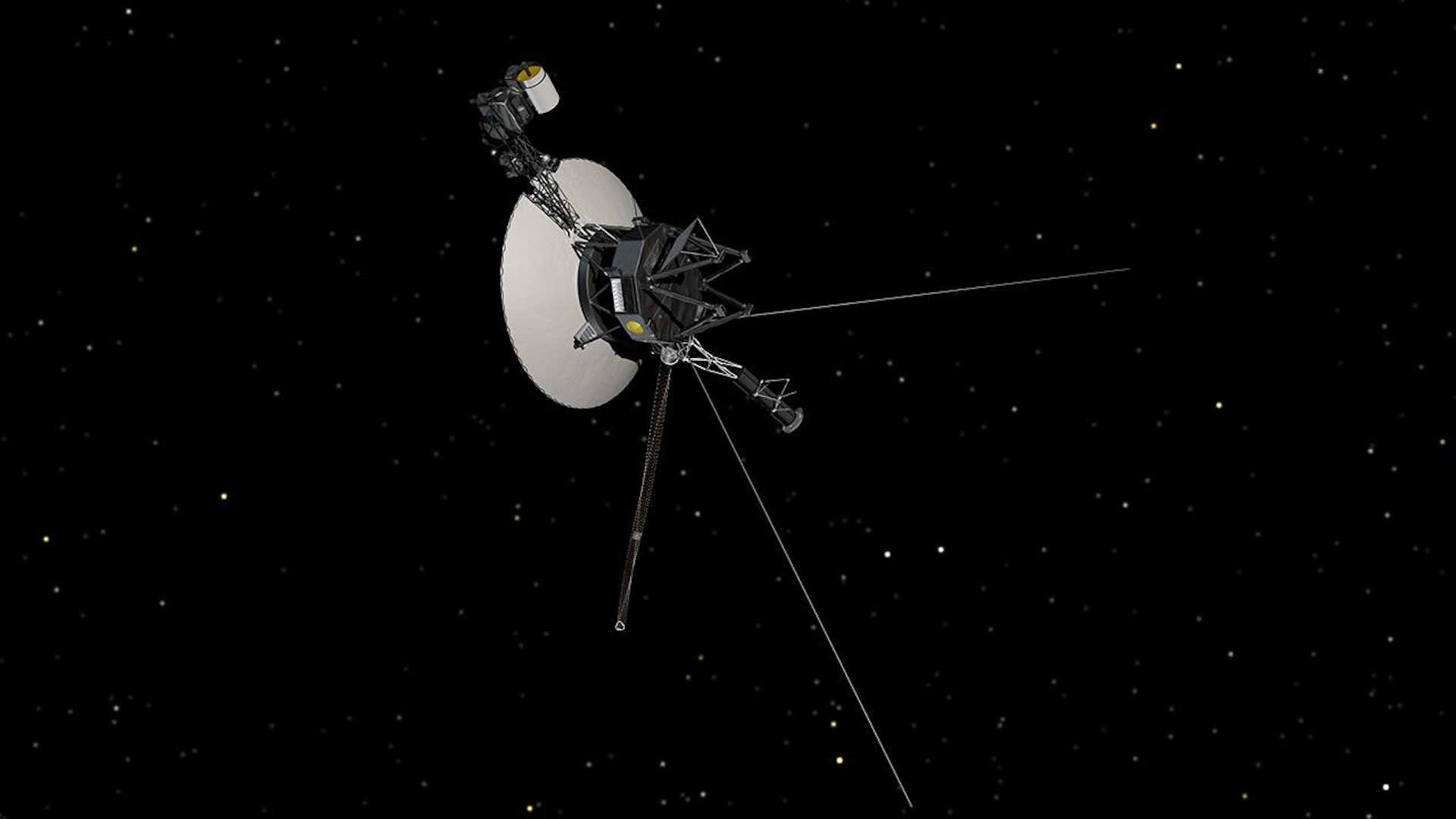

Voyager 1 loses contact with NASA, turns on retro transmitter not used since 1981

NASA lost contact with the interstellar Voyager 1 spacecraft for nearly a week after a technical glitch shut off the probe's main transmitter. Using Voyager's weaker backup transmitter, engineers are assessing the problem from 15 billion miles away.

Scientists lost contact with the interstellar Voyager 1 probe from Oct. 19 to Oct. 24, after a technical malfunction forced the spacecraft's main radio transmitter to shut down, NASA officials wrote in a blog post. Engineers have since established contact with Voyager 1's weaker backup transmitter, which hasn't been used since 1981, while they assess the situation.

"The transmitter shut-off seems to have been prompted by the spacecraft's fault protection system, which autonomously responds to onboard issues," NASA officials wrote in the blog post. "For example, if the spacecraft overdraws its power supply, fault protection will conserve power by turning off systems that aren't essential for keeping the spacecraft flying," including the craft's main radio transmitter, the team added.

With communication restored, it could take several more days or weeks for the underlying issue to be identified.

Interstellar IT

Communicating with Voyager 1 and its twin spacecraft, Voyager 2, isn't simple. Voyager 1, which is currently more than 15 billion miles (24 billion kilometers) from Earth, is the most distant human-made object in the universe. Commands sent from Earth take 23 hours to reach the spacecraft at its current position beyond the edge of the solar system, and responses from Voyager 1 take another 23 hours to return to Earth.

According to NASA, the current communication breakdown began on Oct. 16, after engineers sent Voyager 1 a command to turn on one of its heaters. While the spacecraft should have had ample power to execute this command, the prompt instead triggered Voyager 1's fault protection system.

Two days later, when NASA engineers looked for Voyager 1's response with the Deep Space Network — a worldwide network of radio antennae used to support interplanetary missions — they could not detect the spacecraft's signal. The team eventually found Voyager 1's signal later that day. However, the next day (Oct. 19), communication with Voyager "appeared to stop entirely," according to NASA.

Related: NASA shuts off Voyager 2 science instrument as power dwindles

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Engineers suspect that, during this period, Voyager 1's fault protection system triggered two more times. This forced the spacecraft to turn off its main X-band radio transmitter and switch to its backup S-band transmitter, which uses a different frequency and is "significantly fainter" than the main transmitter, according to NASA.

"While the S-band uses less power, Voyager 1 had not used it to communicate with Earth since 1981," the agency added.

On Oct. 22, engineers sent a command to confirm that the spacecraft was indeed using its backup S-band transmitter. The team successfully reestablished contact with Voyager 1 two days later. NASA engineers are now working to diagnose the issue that triggered Voyager 1's fault protection system and to restore it to normal operations.

Voyager 1 and 2 launched in 1977. They remain the only two spacecraft to pass beyond the heliosphere — the bubble of charged solar particles that wraps around our solar system — making them humanity's first (and, so far, only) interstellar vehicles. As the spacecraft age and move ever farther from Earth, technical issues are becoming more frequent. So far, scientists have managed to troubleshoot these interstellar IT problems from billions of miles away, keeping both Voyager probes functional.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.