Space photo of the week: James Webb telescope spots the ultimate 'super star cluster' deep in the Milky Way

Once blocked from view, the most massive young star cluster in the Milky Way has finally been revealed by the James Webb Space Telescope.

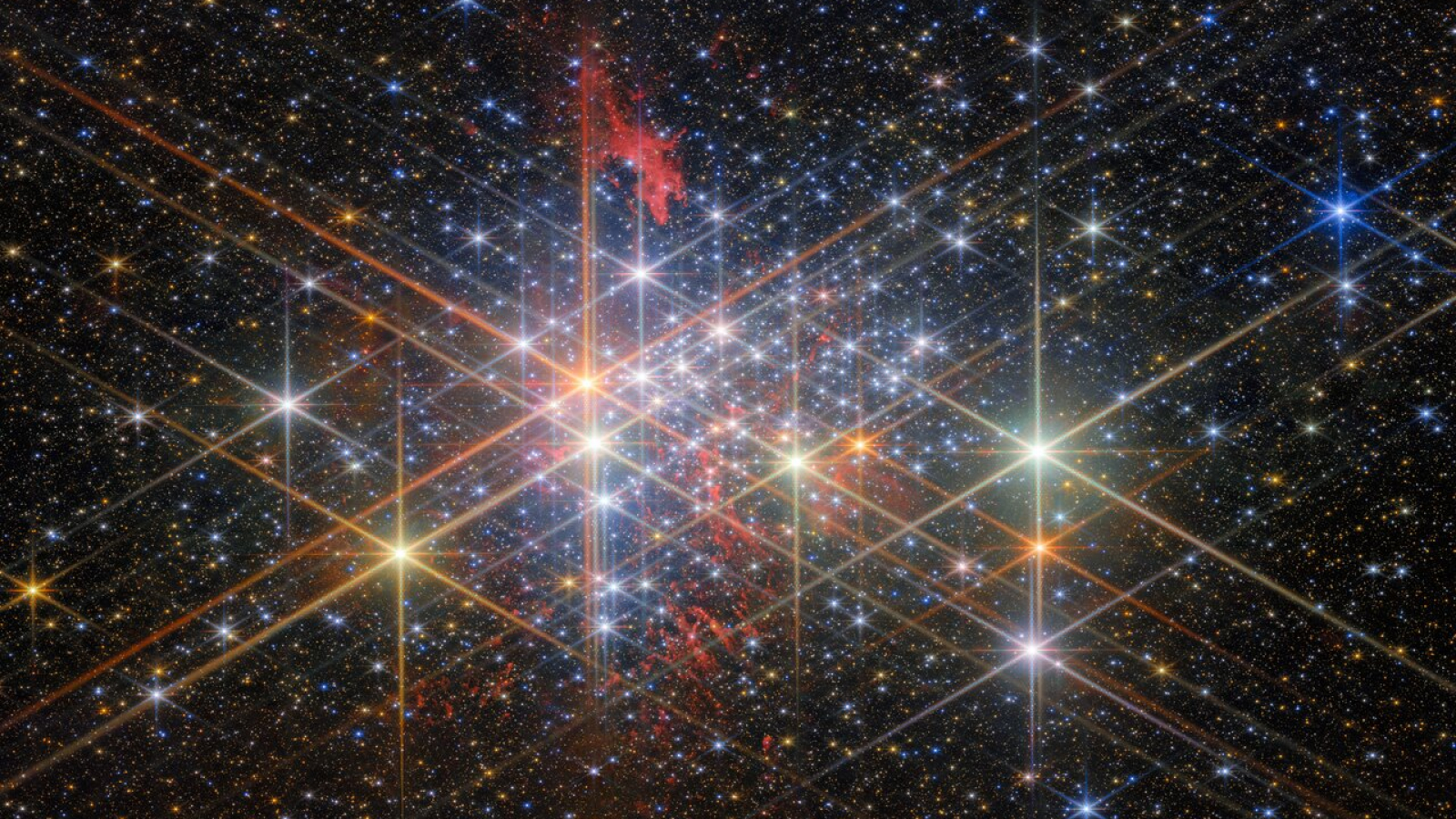

What it is: super star cluster Westerlund 1

Where it is: 12,000 light-years away in the constellation Ara.

When it was shared: Oct. 3, 2024

Why it's so special:

Westerlund 1 is a galactic factory of epic proportions. Visible from Earth's Southern Hemisphere just below the tail of the Scorpion — and close to the core of the Milky Way — it's the largest known star cluster in our galaxy.

It's the ultimate example of a "super star cluster." While most such clusters are about 10,000 times the sun's mass, Westerlund 1 is 50,000 to 100,000 times the solar mass. Some of its hundreds of very massive stars are 2,000 times larger than our sun. If they were in the solar system, they would reach as far as the orbit of Saturn and shine 1 million times brighter than the sun. If Earth orbited a star within Westerlund 1, our night sky would be full of hundreds of stars as bright as the full moon.

Astronomers think that within the next 40 million years — the blink of an eye in cosmic terms — more than 1,500 supernovae (stars exploding at the end of their lives) will light up Westerlund 1. Right now, the cluster is about 3.5 million to 5 million years old.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This image was announced as the latest James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) Picture of the Month and published as both a wide-field view and a panning video. It is something only the JWST could produce because Westerlund 1 is hidden from optical telescopes like Hubble, which can't see through interstellar clouds of gas and dust. JWST's Near Infrared Camera (NIRCam), however, can peer through dust and gas because it sees light beyond the red end of the visible spectrum in infrared wavelengths, which is not scattered by this cosmic debris.

Twists of red gas within the star cluster are visible at the top and center of the image. The bright stars in JWST's image all have six large and two small snowflake-like diffraction spikes because of the way light travels as a wave from the 18 hexagonal mirrors in the telescope's primary mirror. The two horizontal lines through each star result from the light being reflected from the primary mirror to a secondary mirror, which two struts hold in place.

Westerland 1 resembles the Milky Way's past when it produced many more stars. Just a few such clusters survive and offer clues for astronomers trying to figure out what happened in the Milky Way's distant history — and how the most massive stars in our galaxy live and die.

Jamie Carter is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor based in Cardiff, U.K. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners and lectures on astronomy and the natural world. Jamie regularly writes for Space.com, TechRadar.com, Forbes Science, BBC Wildlife magazine and Scientific American, and many others. He edits WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com.