For the 1st time, scientists confirm the moon has a solid iron 'heart' just like Earth

After more than 50 years, scientists finally confirmed that the moon has a solid inner core, just like Earth.

After more than 50 years, scientists have finally uncovered the moon's interior structure, showing that our closest celestial companion has a fluid outer core and a solid inner core, similar to Earth's. A team of researchers from the Côte d'Azur University and the Institute of Celestial Mechanics and Ephemeris Calculations (IMCCE) in France detailed these findings May 3 in a study published in Nature.

Astronomers have puzzled over the moon's structure since well before any probes landed there. A hot debate raged in the first half of the 20th century as to whether the moon was a "primitive" rocky world, like Mars's moons Phobos and Deimos, or whether it had a rich inner geology.

The first hints that the moon had an Earth-like interior came from NASA's Apollo missions. Data gathered by the lunar landers' instruments suggested that the celestial body was differentiated — or layered with denser material at the center and less dense material nearer the surface — as opposed to uniform rock all the way through. Apollo astronauts even left seismometers on the moon, which later revealed that it experiences moonquakes, according to NASA.

Related: Why can we sometimes see the moon in the daytime?

However, scientists were only recently able to sort through the massive data sets from the Apollo missions and other lunar probes to get a clearer picture of the moon's insides. In 2011, research from NASA suggested that the moon's outer core was made of fluid iron, and created a distinct partially melted layer where it met the mantle. The study also hinted that the moon might have an iron-based inner core.

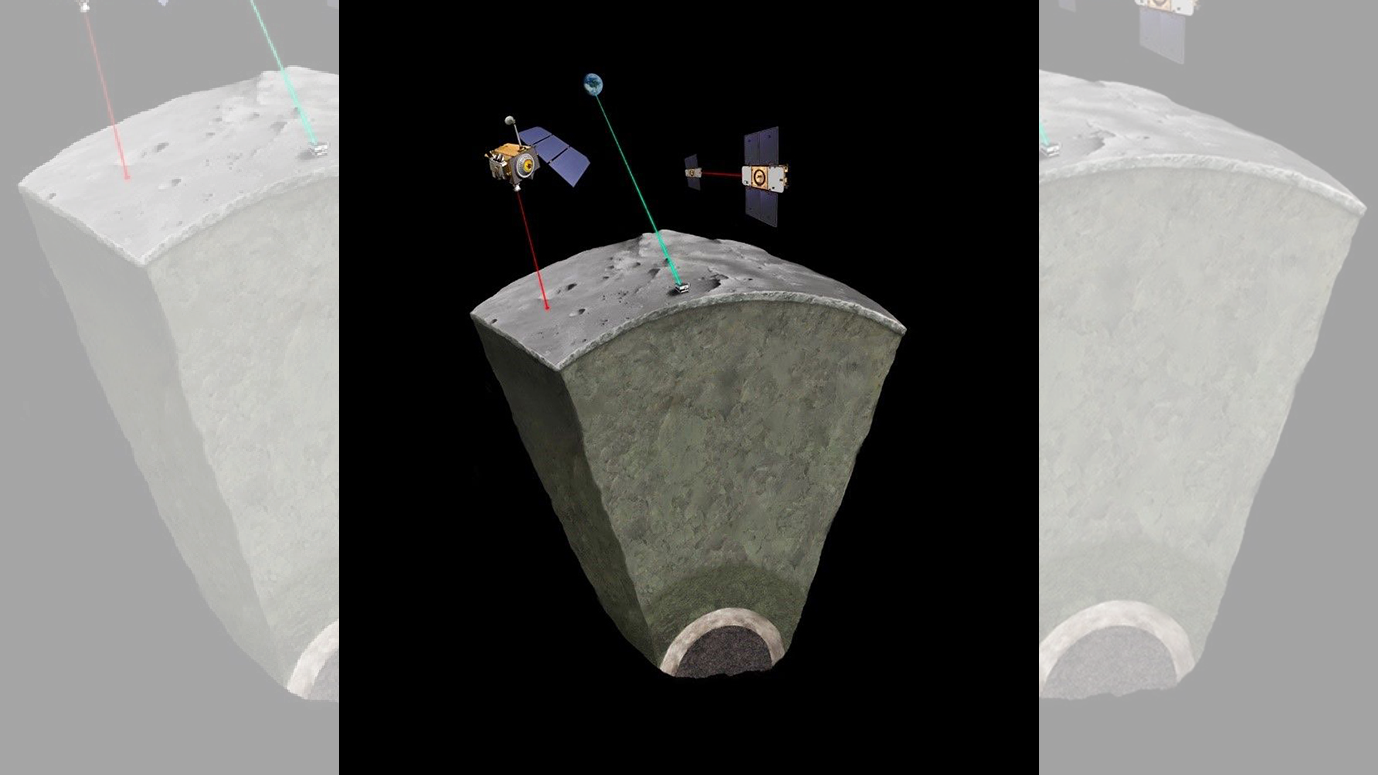

Now, the new study has confirmed that this dense inner core exists. Using a detailed computer model built on geological data from the Apollo program and NASA's GRAIL mission — which used a pair of probes to monitor the moon's gravitational field for more than a year — the researchers determined that the inner core is about 310 miles (500 km) in diameter, or only 15% of the Moon's width. This small size likely explains why scientists had such a hard time detecting it, according to the researchers.

In addition, the study found the first evidence of mantle overturn on the moon — a process by which warmer molten material rises through the mantle like blobs of wax in a lava lamp. According to the researchers, this may explain the presence of iron on the moon's surface.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Gaining a deeper understanding of the moon's inner workings can help scientists further unravel its geologic mysteries, such as what happened to the once-powerful lunar magnetic field. (While the moon has no magnetic field today, rock samples suggest it once had a magnetic field that rivaled Earth's). And as governmental agencies and private space companies gear up for new lunar missions this decade, the promise of more data is right around the corner.

Joanna Thompson is a science journalist and runner based in New York. She holds a B.S. in Zoology and a B.A. in Creative Writing from North Carolina State University, as well as a Master's in Science Journalism from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. Find more of her work in Scientific American, The Daily Beast, Atlas Obscura or Audubon Magazine.