Humanity's future on the moon: Why Russia, India and other countries are racing to the lunar south pole

Half a century after the first humans landed on the moon, global interest is once again rising to visit our celestial neighbor. This time, nations have their sights set on the lunar south pole. Why?

While descending to the moon's surface on July 20, 1969, Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin struggled with alarms from an overwhelmed computer and spotty communication with mission control in Houston, where controllers frantically flipped through notes to identify error codes. After enduring a nerve-wracking 13 minutes and overshooting their landing site by 4 miles (6 kilometers), the crew managed to touch down unharmed near the moon's equator with just 15 seconds' worth of fuel left, and radioed home a much-awaited message: "The Eagle has landed."

Between 1969 and 1972, the U.S. landed 12 astronauts on the moon as part of the Apollo program, which was formed primarily to beat the former Soviet Union to the moon in the heat of the Cold War. Now, more than 50 years after the first human landed on the moon, interest is once again surging to visit our celestial neighbor. This time, though, spacefaring nations are eyeing the lunar south pole, which has become a hotspot for both short- and long-term space exploration.

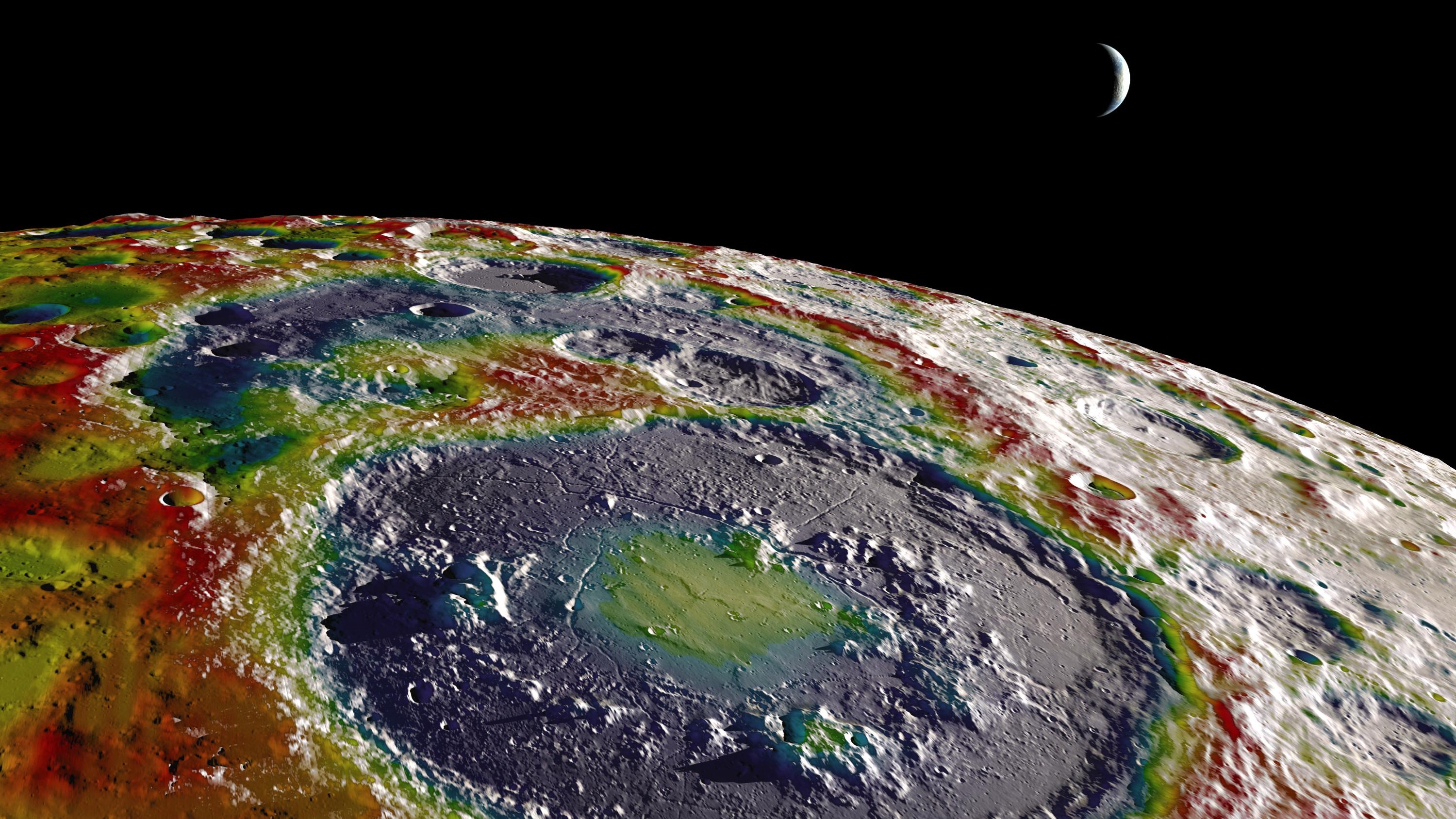

Related: Scientists map 1,000 feet of hidden 'structures' deep below the dark side of the moon

Why focus on the lunar south? Because there, scientists think countless permanently shadowed areas host abundant deposits of frozen water that could be mined for life support and rocket fuel.

However, "it is speculation really; nobody knows" if there's plentiful water there, Martin Barstow, a professor of astrophysics and space science at the University of Leicester in the U.K., told Live Science. "And that's why it is important to go look."

Recently, multiple nations have been trying to do just that.

Race to the lunar south

Russia's Luna 25 lunar probe attempted to land near the south pole on Aug. 19 but crashed after erratic communications following an important orbit maneuver, creating a 33-foot-wide (10 meters) crater on the moon's southeastern region.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A rare glimpse of success in the moon-landing pursuit came on Aug. 23, when India became the first nation to touch down near the lunar south pole with its Chandrayaan-3 mission. There, the country's robotic lander-rover duo spent a lunar day exploring the nearby region. The solar-powered explorers confirmed the presence of sulfur, an infrastructure-building ingredient that could be key to future camps; measured lunar temperature by inserting a probe into the soil for the first time; and likely detected a moonquake. In early September, the mission team put the duo into sleep mode, in hopes that fully charged batteries would push through the bitter night and wake up at the next lunar sunrise.

In 2026, China is planning to send its Chang'e-7 spacecraft on an ambitious endeavor to the lunar south pole. According to the mission plan, the spacecraft will consist of an orbiter, a lander, a rover, and a small, flying probe that will hunt for water ice in shadowed regions. Later this decade, NASA's Artemis moon program aims to land a crew near the south pole for a weeklong mission, with an Australian rover piggybacking on one of the missions.

Home, home on the moon?

For many nations engaged in the new space race, the goal is not just to visit the south pole — but to build a permanent presence there.

"With 50 years of technological progress, anybody can go to the moon — this time, to stay," Jack Burns, director of the NASA-funded Network for Exploration and Space Science at the University of Colorado, Boulder, told Live Science.

NASA's Artemis program, for example, aims to build a cabin on the moon for astronauts to live and work for two months at a time, when they will hone technology by using local resources, like water ice, for life support and rocket fuel generation.

"The idea of manufacturing in space is very interesting to a lot of people, but nobody has really done it yet," Barstow said. "And that, I think, is where we are sitting right now. We all know what we want to do. We can even conceive how we might do it. But we have to do those first engineering tests and see if we actually can."

Related: New poppy seed-sized fuel pellets could power nuclear reactors on the moon

Future space missions will grapple with the challenge of building materials that are both lightweight and strong enough to sustain launch loads. "We don't yet have the facilities to do that," Barstow said. Although getting to the moon's south pole is more challenging than a straightforward path to its equator, we already have the technology to do so. For example, the only way to land on the moon's south pole would be to perform a rocket-powered controlled descent. "The principles of that are fairly straightforward," Barstow said. The more pressing challenge will be nailing down how to land safely.

Ultimately, the pursuit to establish a sustainable presence on the moon will also serve as a stepping stone to get to Mars, scientists say.

Although we may have the technology to send humans to visit the Red Planet, the costs involved are extremely high, and "no one government has the appetite for investing that amount of money that it requires just now," Barstow said. The logistics and human cost of establishing a Mars colony are also an open question in need of extensive research. With the race back to the moon finally kicking off in force, it may still be decades before any "Eagle" lands on Mars.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Space.com, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social