Scientists just found the 'front door' to a massive cave on the moon

The Sea of Tranquility is home to at least one lunar lava tube, which could preserve a pristine and unweathered record of lunar volcanism.

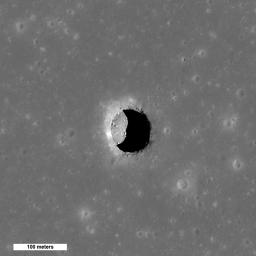

The Moon's surface is pockmarked with more than 200 known pits where rocks and regolith collapsed into depths unknown. New research has found that one of those pits, in Mare Tranquillitatis, collapsed into a lava tube and made an underground cave conduit accessible from the lunar surface.

"We found a sort of front door to enter the subsurface," said Leonardo Carrer, a planetary scientist at the University of Trento, Italy, and first author on the research. Its access to the otherwise shielded lunar subsurface makes this pit a tantalizing site for future human and robotic exploration and could provide new insight into lunar volcanism.

Reflections from below

The Moon was once covered in seas of magma that eventually cooled into the dark basaltic maria visible today. Lunar scientists have long thought that like Earth, the Moon could host other volcanic features such as lava tubes.

Lava tubes form when a lava stream cools and forms a hardened exterior shell. Hot lava continues to flow through it like sludge in a pipe. Eventually, lava flows out of the tube and leaves a hollow conduit that could connect to emptied magma chambers or caves.

RELATED: Volcanic eruptions on the moon happened much more recently than we thought

"We had a lot of evidence on the surface of the Moon suggesting that lunar lava tubes could have existed," Carrer said. Lunar pits, elliptical craters that formed not from an impact but from the surface collapsing into an underground void, have been some of the most compelling evidence for these tubes. More than 200 of these pits have been imaged on the Moon's surface, and scientists speculate that they may be skylights into cave conduits, which happens on Earth when the top of a cave collapses and exposes it to the surface.

Carrer and his colleagues, including fellow University of Trento planetary scientist Lorenzo Bruzzone, wanted to know whether it was possible to map a hidden cave using orbital synthetic aperture radar (SAR) instruments. They first tested this method at two terrestrial cave systems in Lanzarote, Spain, and the Well of Barhout in Yemen, which are both planetary analogs. They used the SAR data to create 3D reconstructions of the two terrestrial cave systems near their entrances.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We verified that the cave characteristics we were measuring from space matched what the speleologists measured on the ground," Carrer said. That gave them the confidence to try out this technique on the Moon.

They focused their attention on the Mare Tranquillitatis pit, a nearly circular sinkhole about 100 meters across and 105 meters deep. The radar data were taken in 2010 by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which sent a signal down into the pit at an angle and received a radar reflection from the bottom.

"We could detect from this pit…a reflection that clearly proved an opening on the bottom and the entrance of a cave, which probably is a part of a lava tube," Bruzzone said. "It was quite easy to understand the signals seen on the Moon thanks to the Earth validation."

They fed those radar measurements into their computer model to create a 3D visualization of the lava tube with estimates of its dimensions. The model suggests that the entrance is at least 45 meters wide. Depending on how sharply the conduit slopes downward, it extends 30–80 meters from the entrance and reaches 135–175 meters below the lunar surface. The researchers published this research in Nature Astronomy.

Pristine, unweathered lunar history

"Studying the rocks there, since they are pristine rocks not altered by the harsh surface, could give a lot of insight about the lunar volcanism and the history of volcanism on the Moon.

Leonardo Carrer

"[This] analysis certainly indicates that there's a passage that goes deeper than we've been able to see with visible-wavelength images," said Robert Wagner, a planetary scientist at Arizona State University in Tempe who was not involved with this research. The passage might not connect with a larger cave, he cautioned, "but this new study is consistent with present-day access to a lava tube. The next step is really to send a mission to this pit to go in and directly investigate what's down there."

With international focus on lunar exploration and even permanent habitation, lunar caves are of interest for their potential to shield astronauts from radiation. But Bruzzone and Carrer are more excited by the geologic history that may be preserved inside this lava tube within rocks shielded from weathering and alteration by the solar wind and cosmic rays.

"Studying the rocks there, since they are pristine rocks not altered by the harsh surface, could give a lot of insight about the lunar volcanism and the history of volcanism on the Moon," Carrer said.

What's more, if there is one intact lunar lava tube, there may be many, Wagner added. The prevalence of subsurface lava tubes could shed light on how lunar magma moved, cooled, and settled.

"Finding one that is completely intact, apart from one comparatively tiny hole in the roof, indicates that there may be quite a lot of deeply buried conduits waiting for us to get down on the surface with seismometers, gravimeters, or radar in order to find them," Wagner said.

However, exploring whether other pits connect with lava tubes will have to wait for better radar coverage of the Moon. "This cannot be seen with an optical camera," Bruzzone said, and currently available lunar radar data either are not of high enough resolution to study smaller pits or do not cover the maria regions where pits have been found.

"With the data that we have," he added, "it is not possible to clearly identify reflections that prove the accessibility from a pit and then into a cave."

This article was originally published on Eos.org. Read the original article.

Kimberly is a News and Features Writer for Eos.org. She joined the Eos staff in 2017 after earning her Ph.D. studying extrasolar planets. Kimberly covers space science, climate change, and STEM diversity, justice, and education.