Overlooked Apollo data from the 1970s reveals huge record of 'hidden' moonquakes

A reanalysis of 50-year-old Apollo mission data long abandoned by NASA has revealed 22,000 previously unrecognized moonquakes, almost tripling the known number of seismic lunar events.

The moon is much more seismically active than we realized, a new study shows. A reanalysis of abandoned data from NASA's Apollo missions has uncovered more than 22,000 previously unknown moonquakes — nearly tripling the total number of known seismic events on the moon.

Moonquakes are the lunar equivalent of earthquakes, caused by movement in the moon's interior. Unlike earthquakes, these movements are caused by gradual temperature changes and meteorite impacts, rather than shifting tectonic plates (which the moon does not have, according to NASA). As a result, moonquakes are much weaker than their terrestrial counterparts.

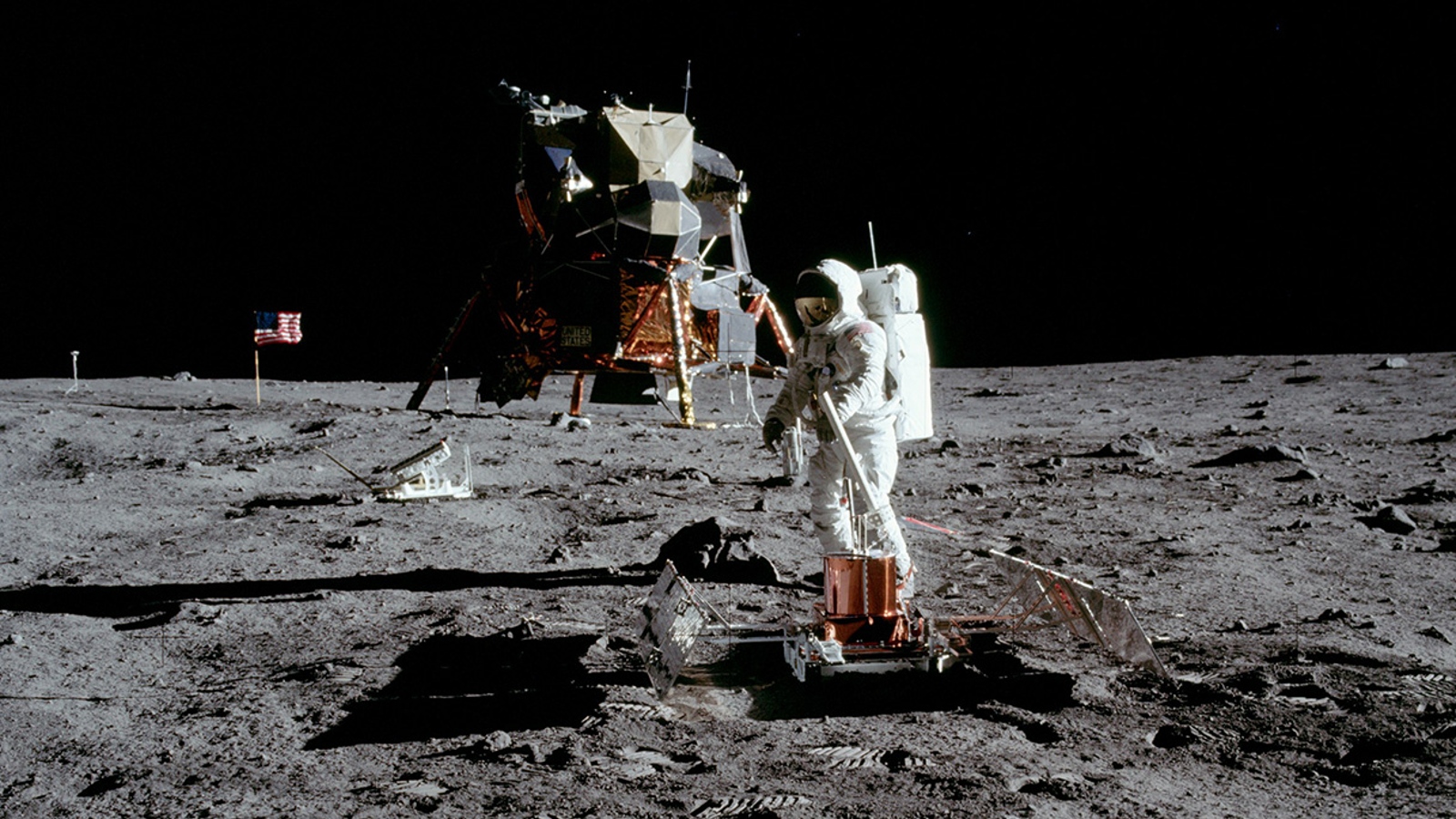

Between 1969 and 1977, seismometers deployed by Apollo astronauts detected around 13,000 moonquakes, which until now were the only such lunar seismic events on record. But in the new study, one researcher spent months painstakingly reanalyzing some of the Apollo records and found an additional 22,000 lunar quakes, bringing the total to 35,000.

The findings were presented at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, which was held in Texas between March 13 and March 17, and are in review by the Journal of Geophysical Research.

The newly discovered moonquakes show "that the moon may be more seismically and tectonically active today than we had thought," Jeffrey Andrews-Hanna, a geophysicist at the University of Arizona who was not involved in the research, told Science magazine. "It is incredible that after 50 years we are still finding new surprises in the data."

Apollo astronauts deployed two types of seismometers on the lunar surface: one capable of capturing the 3D motion of seismic waves over long periods; and another that recorded more rapid shaking over short periods.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The 13,000 originally identified moonquakes were all spotted in the long-period data. The short-period data has been largely ignored due to a large amount of interference from temperature swings between the lunar day and night, as well as issues beaming the data back to Earth, which made it extremely difficult to make sense of the numbers.

"Literally no one checked all of the short-period data before," study author Keisuke Onodera, a seismologist at the University of Tokyo, told Science Magazine.

Not only had this data gone unchecked, but it was almost lost forever. After the Apollo missions came to an end, NASA pulled funding from lunar seismometers to support new projects. Although the long-period data was saved, NASA researchers abandoned the short-period data and even lost some of their records. However, Yosio Nakamura, a now-retired geophysicist at the University of Texas in Austin, saved a copy of the data on 12,000 reel-to-reel tapes, which were later digitally converted.

"We thought there must be many, many more [moonquakes in the data]," Nakamura told Science magazine. "But we couldn't find them."

In the new study, Onodera spent three months going back over the digitized records and applying "denoising" techniques to remove the interference in the data. This enabled him to identify 30,000 moonquake candidates, and after further analysis, he found that 22,000 of these were caused by lunar quakes.

Not only do these additional quakes show there was more lunar seismic activity than we realized, the readings also hint that more of these quakes were triggered at shallower points than expected, suggesting that the mechanisms behind some of these quakes are more fault-orientated than we knew, Onodera said. However, additional data will be needed to confirm these theories.

Recent and future moon missions could soon help scientists to better understand moonquakes. In August 2023, the Vikram lander from India's Chandrayaan-3 mission detected the first moonquake since the Apollo missions on its third day on the lunar surface.

Onodera and Nakamura hope that future NASA lunar seismometers on board commercial lunar landers such as Intuitive Machine's Odysseus lander, which became the first U.S. lander to reach the moon for more than 50 years in February, will confirm what the new study revealed.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.