The moon is shrinking, causing landslides and moonquakes exactly where NASA wants to build its 1st lunar colony

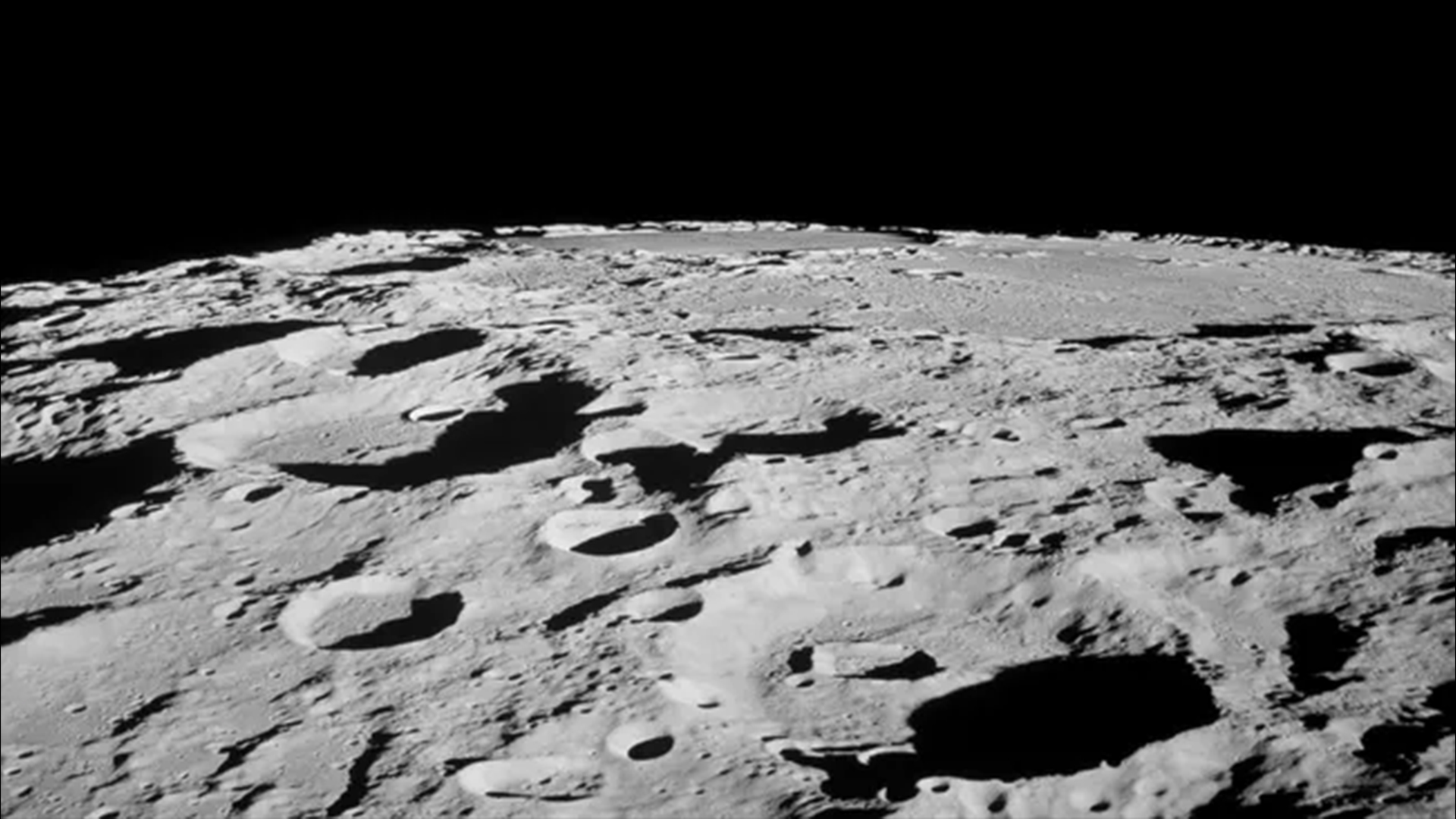

When plotting sites for crewed lunar landings — ranging from the forthcoming Artemis missions to eventual lasting moon settlements — mission planners must account for tons of lunar parameters. For instance, the shape of the terrain could make or break a mission and a possible high volume of buried water could make one spot much more tantalizing than its drier counterpart. But now, geologists suggest it's also important to keep moonquakes and lunar landslides in mind.

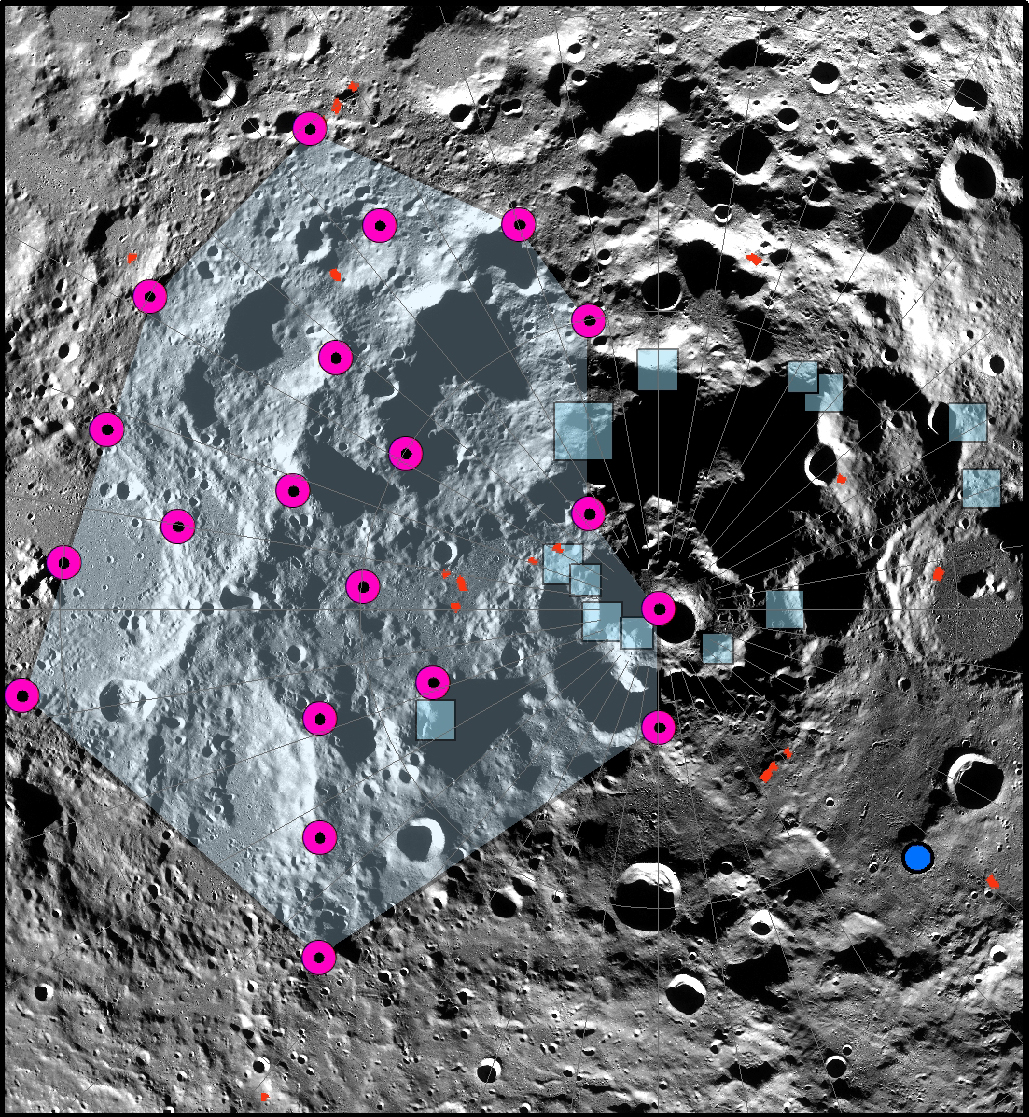

As the scientists emphasize, this is no longer an academic question. Researchers examining the moon's south polar region — which sits near the planned landing side of Artemis 3, set to touch down in 2026 — have identified fault lines whose slips triggered a major moonquake about 50 years ago.

Certain Apollo missions carried seismometers along with them. On March 13, 1973, a particularly strong moonquake rattled those seismometers from the general direction of the moon's south pole. Decades later, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter flew over the south pole and discerned a webwork of fault lines. With new models, researchers have connected those faults with that moonquake.

The research further adds to our picture of what moonquakes are like in general. In principle, moonquakes are like earthquakes. Both are caused by shifting faults; in the moon's case, they're caused by creases that form on the moon's surface as it shrinks. If you're asking yourself why in the world the moon would be shrinking, well, it's basically because the lunar interior has cooled over the last few hundred million years. It's sort of like a raisin shriveling up, scientists say, which also helps us visualize the creation of those creases.

Further, the moon's surface is much less tightly packed than Earth's, often consisting of loose particles that can be thrown up and strewn about by impacts. As a result, moonquakes are even more likely to trigger landslides than earthquakes are.

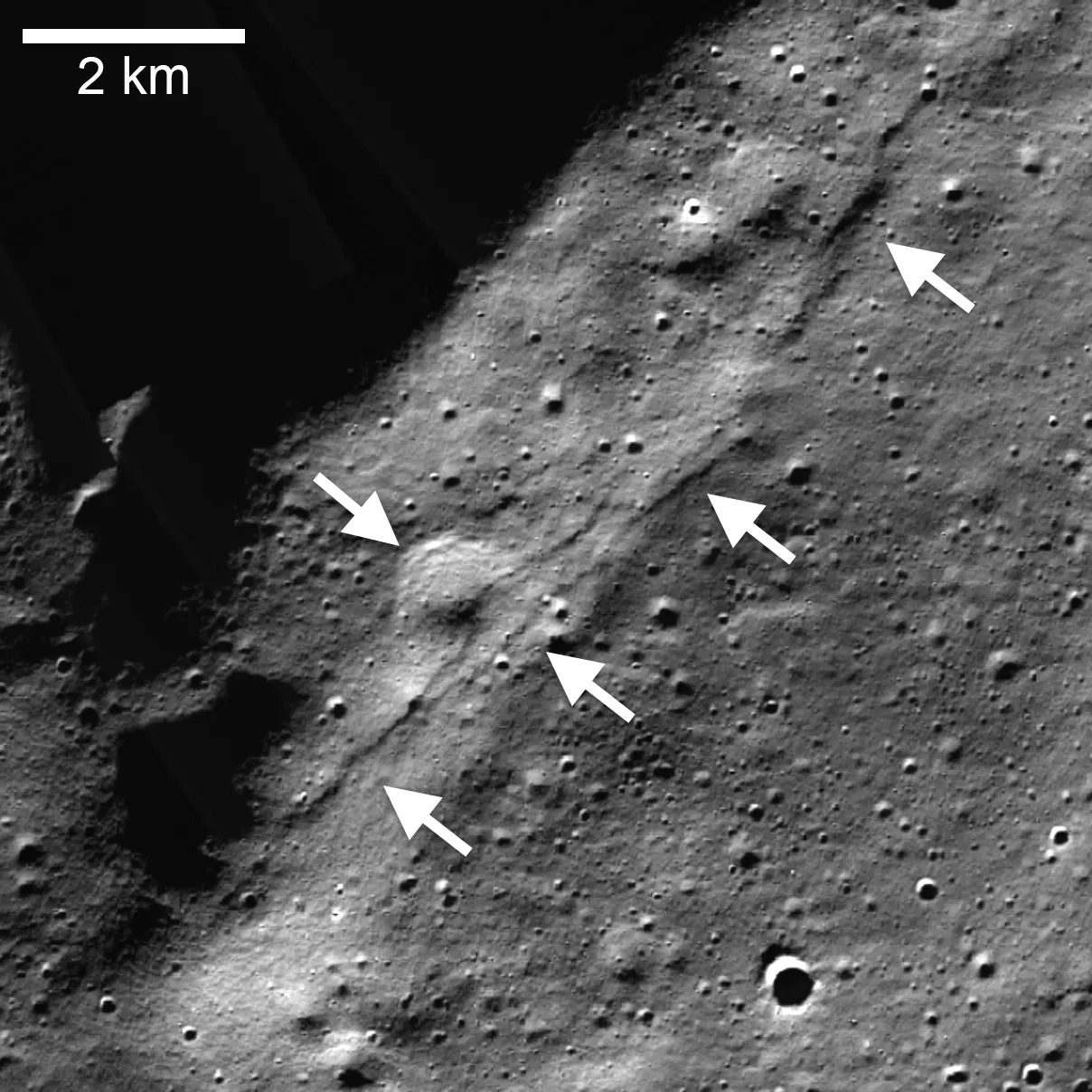

According to the researchers, as the day when human boots tread the moon yet again draws nearer, the humans in question will have to plan for the possibility that the ground under those boots is not as stable as they might hope. The researchers' model suggests, for example, that the walls of Shackleton Crater — famed for its ice — are vulnerable to landslides.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"As we get closer to the crewed Artemis mission’s launch date, it's important to keep our astronauts, our equipment and infrastructure as safe as possible," said Nicholas Schmerr, a geologist and one of the researchers, in a statement. "This work is helping us prepare for what awaits us on the moon — whether that’s engineering structures that can better withstand lunar seismic activity or protecting people from really dangerous zones."

The research was published on Jan. 25 in The Planetary Science Journal.

Originally posted on Space.com.

Rao is a freelance science journalist based in New York and is a contributor to Live Science’s sister site Space.com, as well as Popular Science, EEE Spectrum and Gizmodo. Rao has a bachelor’s degree in Physics and English from Vanderbilt University, and a master’s degree in Science, Health and Environmental Reporting from New York University.