The oldest evidence of Earth's atmosphere may be hiding in rocks on the moon

The moon hasn't had a magnetic field for 4.36 billion years. That means it could hold fragments of the ancient Earth.

The oldest evidence of Earth's ancient atmosphere may be lurking in rocks from the moon, a new study suggests.

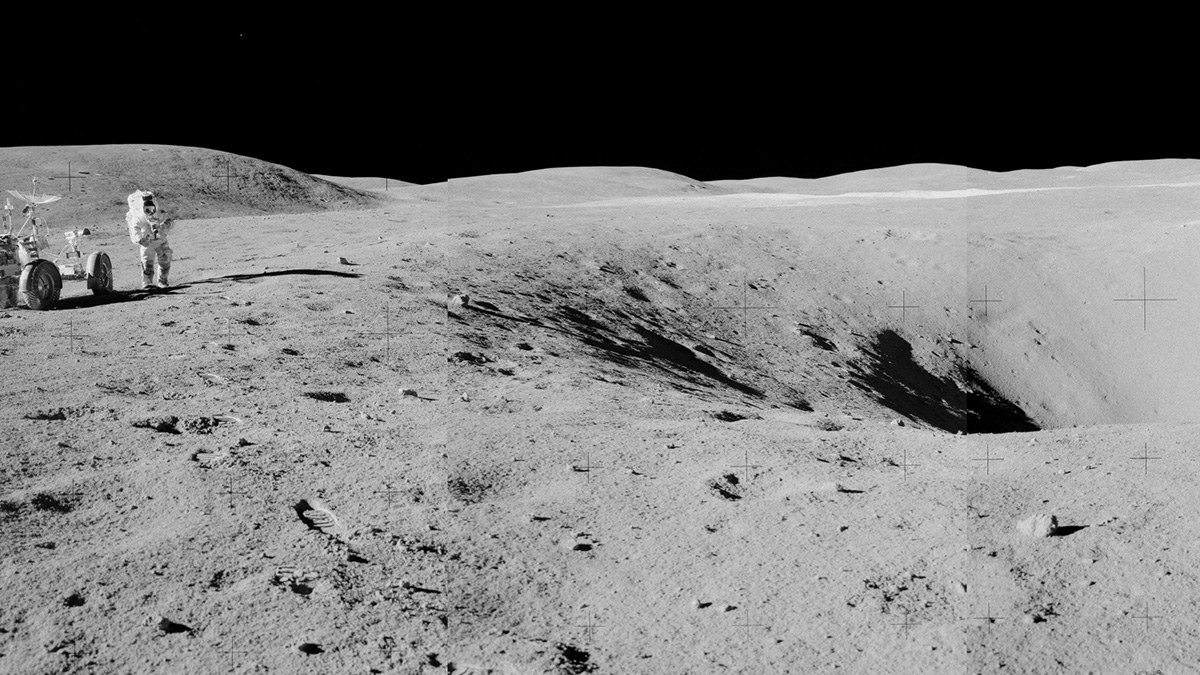

That's the takeaway from a new analysis of moon rocks that Apollo astronauts brought back to Earth 50 years ago.

At the time, scientists detected traces of magnetism locked in the rocks — a sign that the moon had once had a magnetic field, much like Earth's. This was perplexing, because magnetic fields are driven by a planet or moon's core, and the moon's core is tiny, study co-author John Tarduno, a professor of Earth and environmental sciences at the University of Rochester, told Live Science.

But the new study shows that the moon has not had a magnetic field for at least 4.36 billion years.

Their new study, published Friday (Sept. 6) in the journal Communications Earth & Environment, finds that the moon could only have been protected by a magnetic field in the first 140 million years of its existence. That's exciting, Tarduno told Live Science, because it means the moon could hold a record of Earth's earliest existence that has long been wiped from our planet itself. Without a magnetic field to protect it, the moon could have picked up ions from Earth's atmosphere 4.36 billion years ago.

"One of the mysteries about Earth and Earth's evolution is really what was the earliest composition of Earth's atmosphere?" Tarduno said. "We have no way of really getting measurements of this on Earth."

Related: Scientists map 1,000 feet of hidden 'structures' deep below the dark side of the moon

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Very few rocks older than 3.5 billion years remain on Earth, and those that do have been heavily altered by Earth's ever-churning tectonic plates. The moon, by contrast, is geologically quiet, Tarduno said, and there are layers of lunar soil — called regolith — that may have gone undisturbed for billions of years.

"If we could find a place on the moon that recorded this really old regolith material we might have a way to deduce what the early Earth's atmosphere was from direct measurements," Tarduno said.

Magnetic fields are generated by the motion of magnetic materials at the core of a planet or moon, and they protect the surface of that planetary body from the solar wind, which is a flow of charged particles from the sun. Certain iron-bearing rocks can record the status of the magnetic field at the time that they cooled and solidified because the magnetic minerals in the rocks will line up according to the magnetic field and get locked in that orientation.

In 2021, Tarduno and his team found that the moon didn't have a magnetic field 3.9 billion years ago. While the whole rocks show some magnetization overall, this may be caused by meteor impacts, Tarduno said. Single crystals in the rock, a better record of geomagnetic fields, had no particular magnetic orientation, Tarduno and his team showed.

In the new study, Tarduno looked at the older lunar samples and pushed the date of possible magnetism on the moon by 400 million years. That's exciting, Tarduno said, because that timeframe represents Earth's very first eon, the Hadean. There are no rocks from the Hadean left on Earth, and the planet's early atmosphere is a mystery.

The sun, a younger star then, was less luminous, raising questions of why early Earth wasn't an inert ice ball. The greenhouse gases needed to heat the planet to thaw under that dim sun would have created a haze, not unlike that seen on Saturn's moon Titan today. That haze would deflect sunlight, making it even harder to get a warm planet where life could thrive.

"It's super interesting in terms of people thinking about planetary evolution and the question of habitability," Tarduno said. "If we can't understand Earth, how can we say anything about the evolution of other planets?"

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.