10 supercharged solar storms that blew us away in 2024

The sun's most active phase, solar maximum, officially arrived in 2024, triggering some explosive solar storms and colorful auroras. Here are 10 of our favorite solar outbursts this year.

The sun has been in full force in 2024 thanks to the start of solar maximum. The explosive peak of the sun's roughly 11-year solar cycle officially arrived this year after months of speculation.

As a result, sunspots have constantly littered the sun's surface this year in numbers not seen for decades. These dark spots have been spitting out frequent and powerful solar storms that occasionally collide with Earth, triggering radio blackouts and major geomagnetic disturbances. And this may be only the start of what's to come.

From supercharged explosions and global auroras to "cannibal" coronal mass ejections and eruptions during a total solar eclipse, here are 10 electrifying solar storm stories from 2024.

Related: Watch the sun erupt in 1st images from NOAA's groundbreaking new satellite

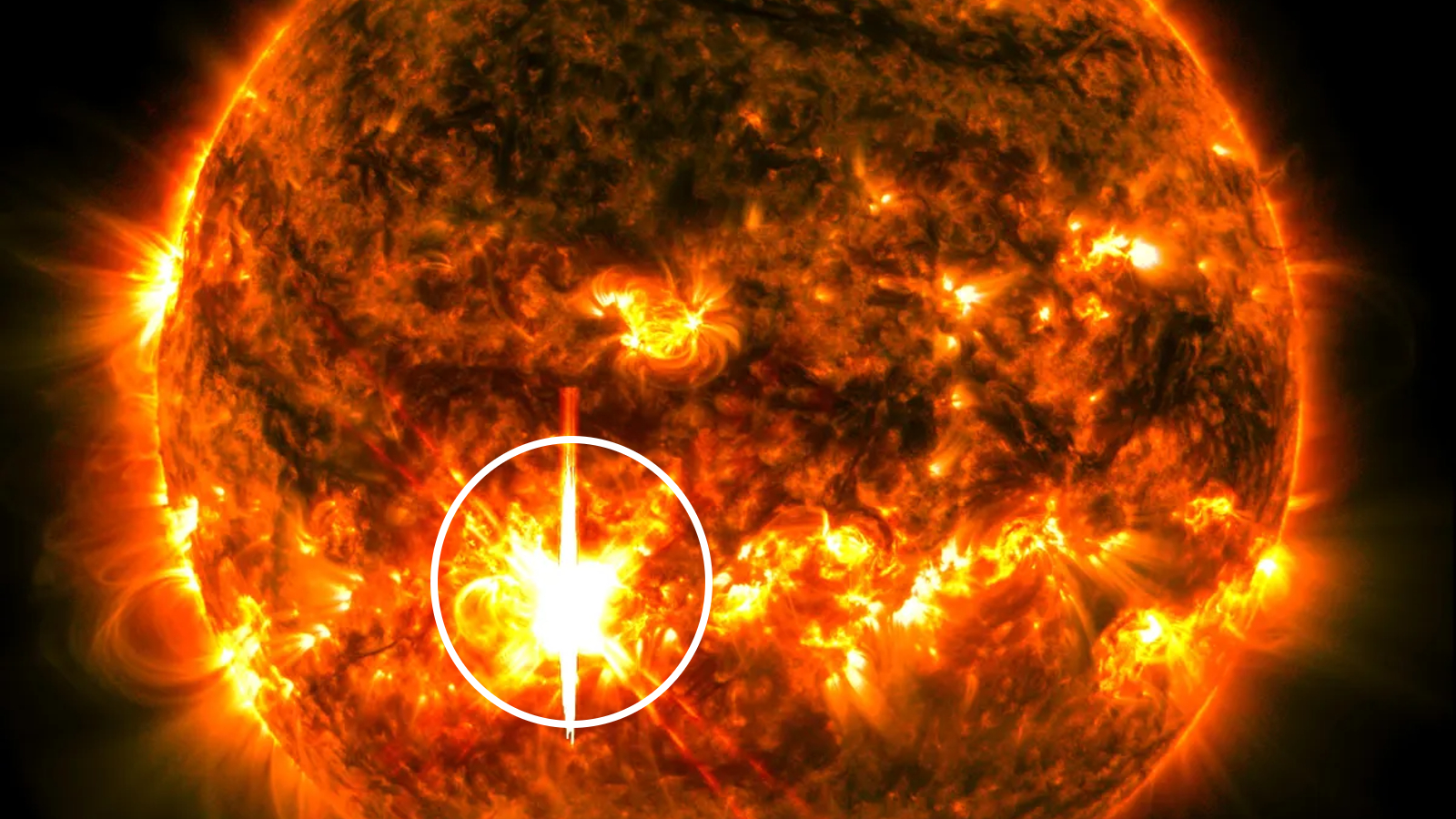

Biggest solar flare (yet)

On Oct. 3, the sun unleashed the most powerful solar flare of the current solar cycle yet. The X-class flare — the most powerful type the sun is capable of producing — reached a magnitude of X9, making it the sun's strongest outburst in more than seven years.

The supercharged flare erupted from a sunspot that had already spit out a massive X7.1 flare just days earlier and launched a cloud of charged particles, known as a coronal mass ejection (CME), at Earth. However, the solar storm only briefly grazed our planet on this occasion.

This superpowered explosion followed another hefty X8.7 outburst in May.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Best auroras in centuries

In early May, people across the globe were treated to the most widespread auroral display in living memory.

The extraordinary light show, which lasted between May 10 and May 12, was the result of a massive disturbance in Earth's magnetosphere known as a geomagnetic storm. This disturbance was the largest of its kind in more than 21 years. It was triggered when at least five smaller CMEs erupted consecutively from a single enormous sunspot and smashed into our planet one by one.

Some NASA experts even suggested this may have been the best auroral display in the past 500 years.

Solar eclipse eruptions

On April 8, millions of people across North America witnessed a total solar eclipse as the moon passed directly between Earth and the sun, casting a giant shadow across our planet.

Many people were hoping to see a solar flare during the event, and several people thought they did when they spotted large, pink flames around the obscured sun's edge. But what people were actually seeing were large loops of plasma, known as solar prominences, towering above the solar surface.

Solar prominences form above sunspots when looping magnetic fields poke through the solar surface and drag fiery plasma with them. These structures can snap and fling plasma out into space in the form of CMEs.

More auroras after "severe" storm

On Oct. 10-11, another wave of widespread auroras swept across large parts of the globe.

This time, the auroras were caused by a "severe" geomagnetic storm, which was triggered by an X1.8 solar flare that launched a single CME right at Earth.

On this occasion, the northern lights were visible as far south as northern California and Alabama. But they did not reach as far as the auroras from May's superstorm, when the light shows were spotted close to the equator.

Some farmers in the U.S. also reported that their tractors were dancing from side to side during October's disturbance as solar radiation interfered with GPS signals.

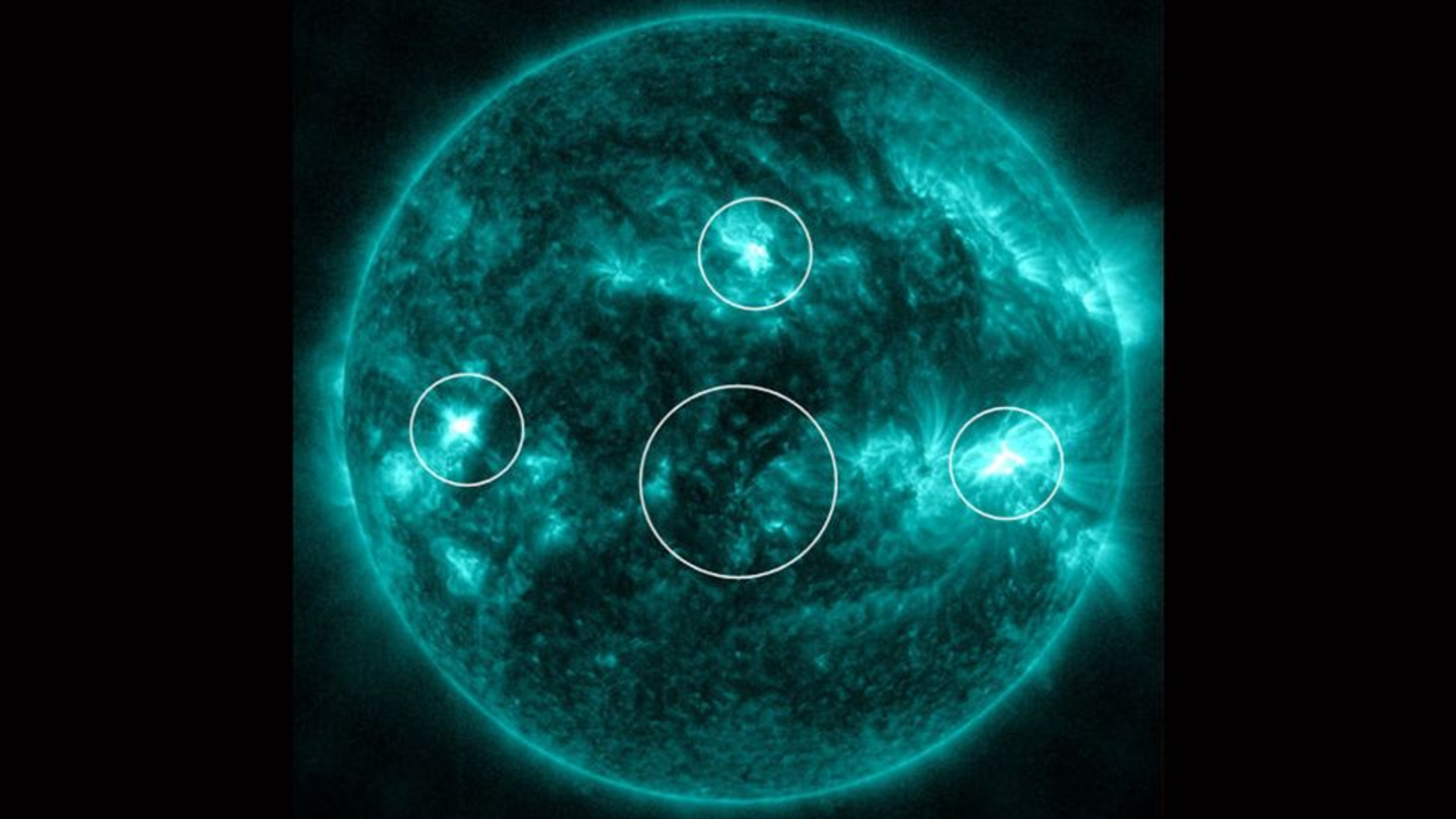

Simultaneous "quadruple" solar flare

On April 23, a rare phenomenon occurred across large parts of the sun: a quadruple solar flare.

The unique solar storm involved four sizable outbursts erupting simultaneously from different spots across the sun's surface. While this initially appeared to be a coincidence, the four flares were part of a single explosion.

These eruptions, known as sympathetic solar flares, occur when a single flare sets off a chain reaction at other sunspots connected to it via invisible magnetic-field lines. This phenomenon normally creates only two or three simultaneous blasts, making this example even more special.

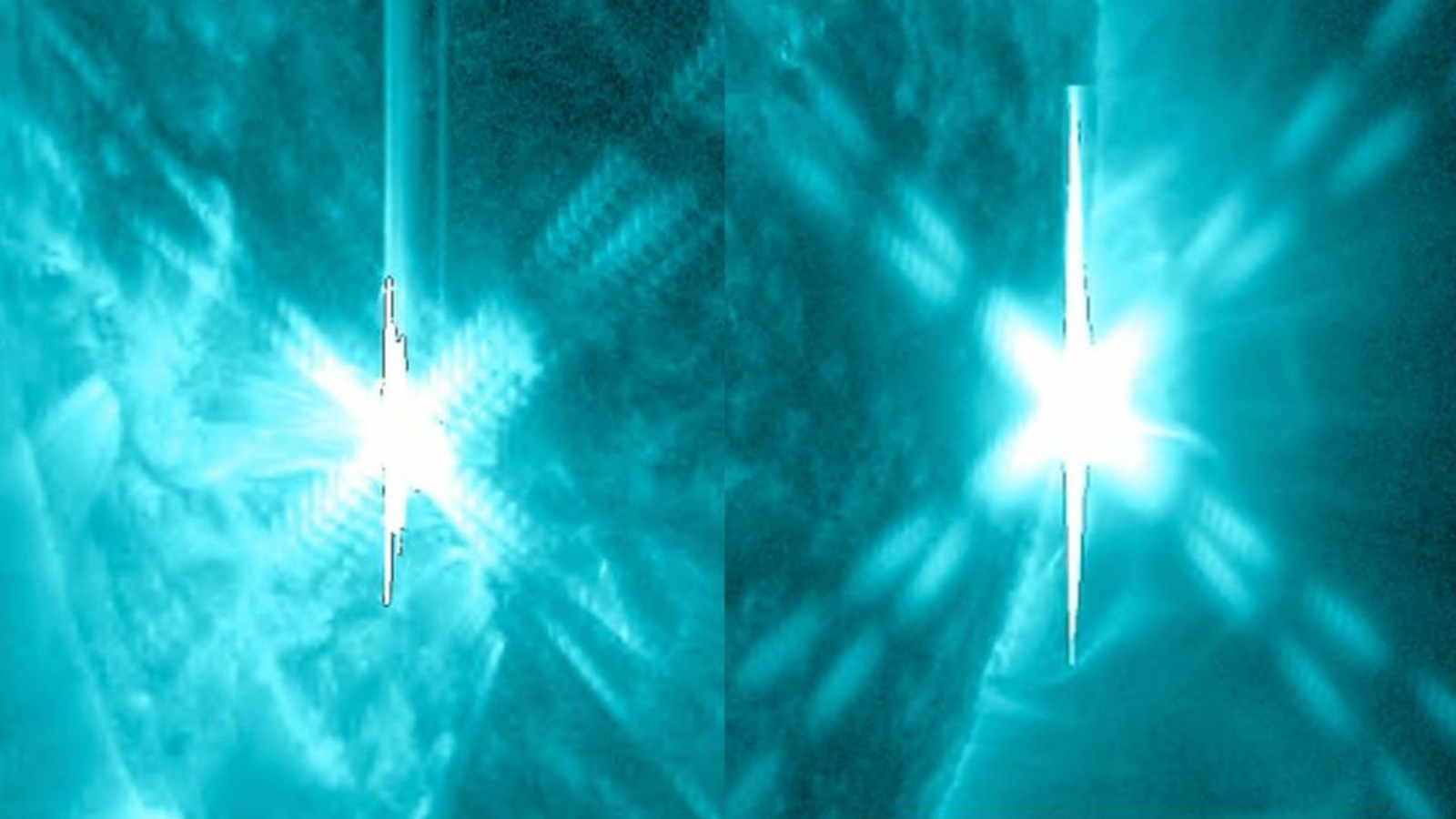

Triple X-class flares

One X-class solar flare is scary enough. But in late February, X-class triplets erupted from the sun.

Unlike the quadruple solar flare in April, these flares were not sympathetic. Instead, a single hyperactive sunspot fired off the massive flares one by one in less than 24 hours. The successive outbursts had respective magnitudes of X1.8, X1.7 and X6.3, which was a record for the current solar cycle at the time.

None of these flares launched CMEs. However, they did unleash waves of radiation that triggered large radio blackouts. At the time, people suspected these blackouts may have been responsible for disruption to multiple cell service providers, including AT&T, Verizon and T-Mobile. However, that turned out to not be the case.

Quick-fire double flare

On Aug. 5, a pair of X-class flares erupted from the sun in quick succession less than two hours apart.

However, unlike February's triple flares, these outbursts did not come from the same sunspot. Instead, they were launched by adjacent dark patches.

This quick-fire outburst was followed by another widespread geomagnetic storm around a week later. However, these flares did not cause the storm, as they did not launch any CMEs at Earth.

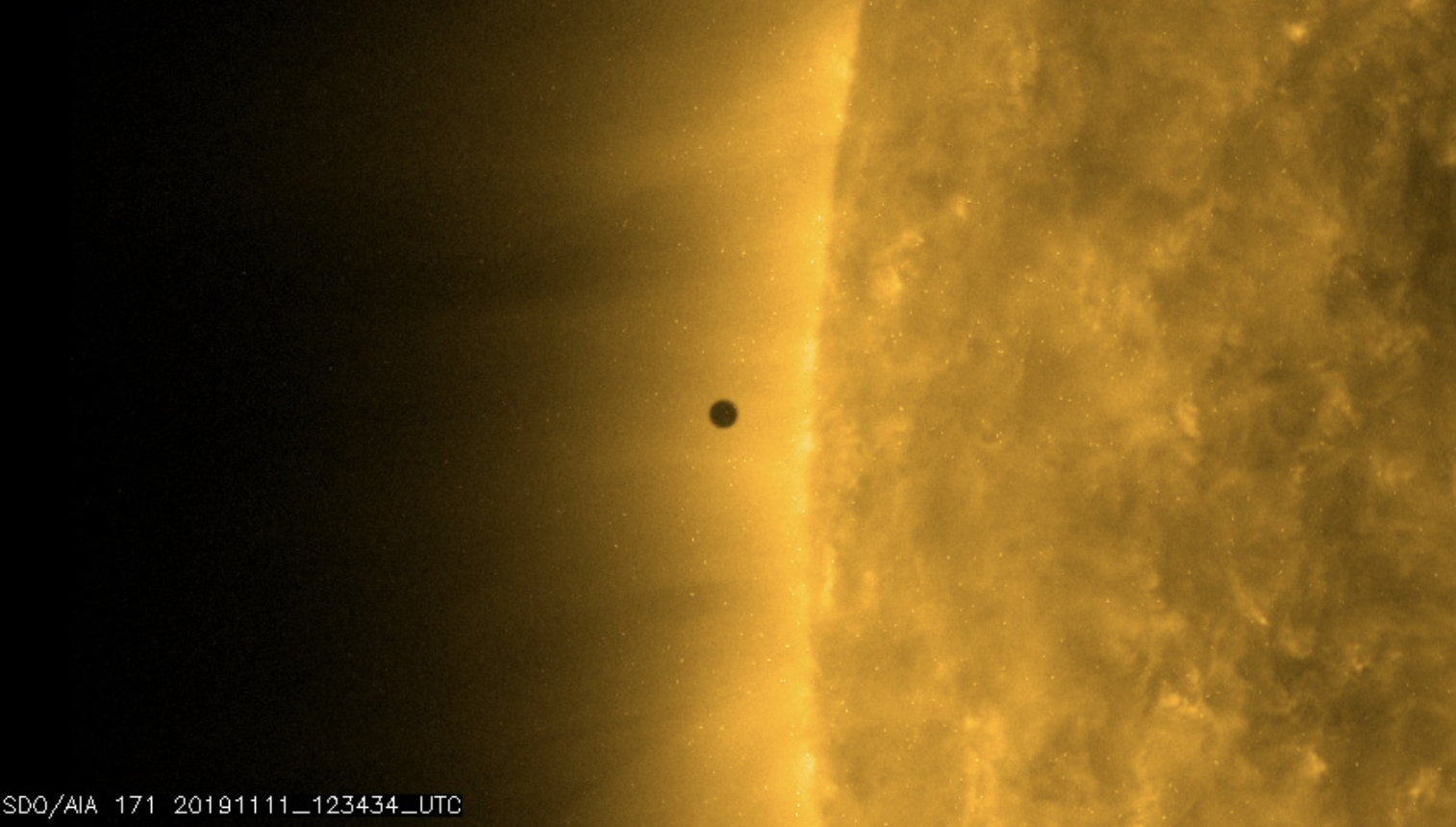

Hidden eruption battered Mercury

Not all solar flares are easy to see. In early March, a hidden eruption on the far side of the sun launched a massive CME that hurled right into Mercury.

Images of plasma emerging from the sun's far side suggested that the eruption may have spanned up to 310,000 miles (500,000 kilometers), which is around 40 times wider than Earth.

Mercury is often blasted with CMEs due to its proximity to our home star. As a result of this bombardment, Mercury has no remaining atmosphere, which means the planet's surface is fully exposed to the full force of these solar storms. When solar particles hit Mercury's unprotected surface, they slow down rapidly, which causes them to release energy in the form of X-rays, similar to auroras.

"Cannibal" CME

In early August, Earth was hit by an unusually large and complex CME that formed via an act of solar cannibalism.

The sun fired off two CMEs back-to-back. The second eruption caught up to, and engulfed, the first one, creating a combined cloud of plasma and radiation known as a "cannibal" CME. When the conjoined solar storms did hit Earth, they triggered another surge of widespread auroras but not at the same levels seen in May or October.

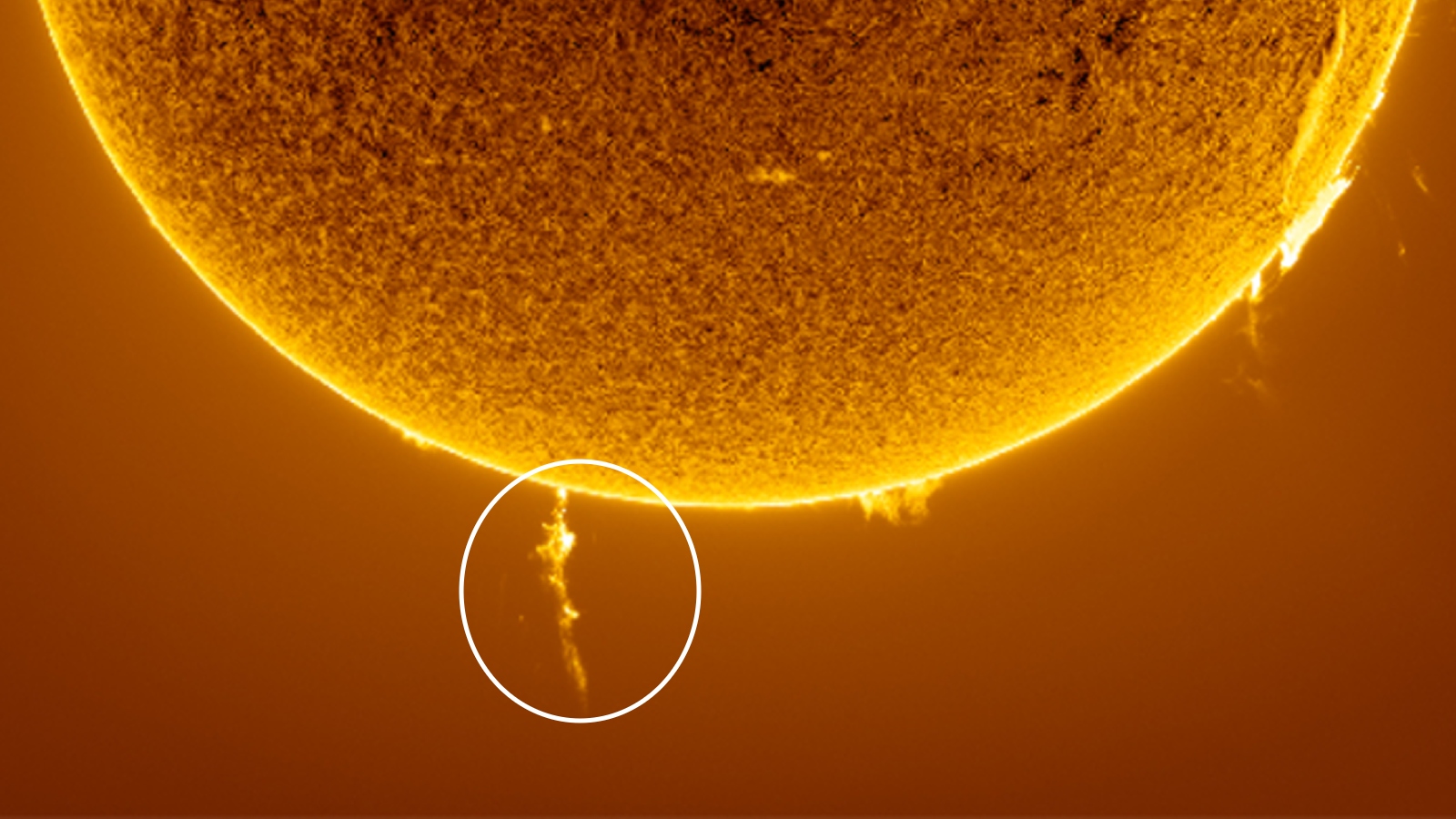

Rare polar "crown"

On Feb. 17, a solar flare exploded from a sunspot near the sun's south pole, releasing a gigantic column of plasma that towered around 124,000 miles (200,000 km) above the solar surface. This rare eruption is known as a polar crown prominence.

Normally, outbursts like these occur closer to the sun's equator, because the star's magnetic field is much stronger near the poles, which suppresses sunspot growth. However, as the sun's magnetic field weakens during solar maximum, polar eruptions emerge. The storm's unusual orientation meant that any resulting CMEs were directed away from the solar system's planets.

A photographer who captured the scene described it as "a wonderful spectacle."

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.