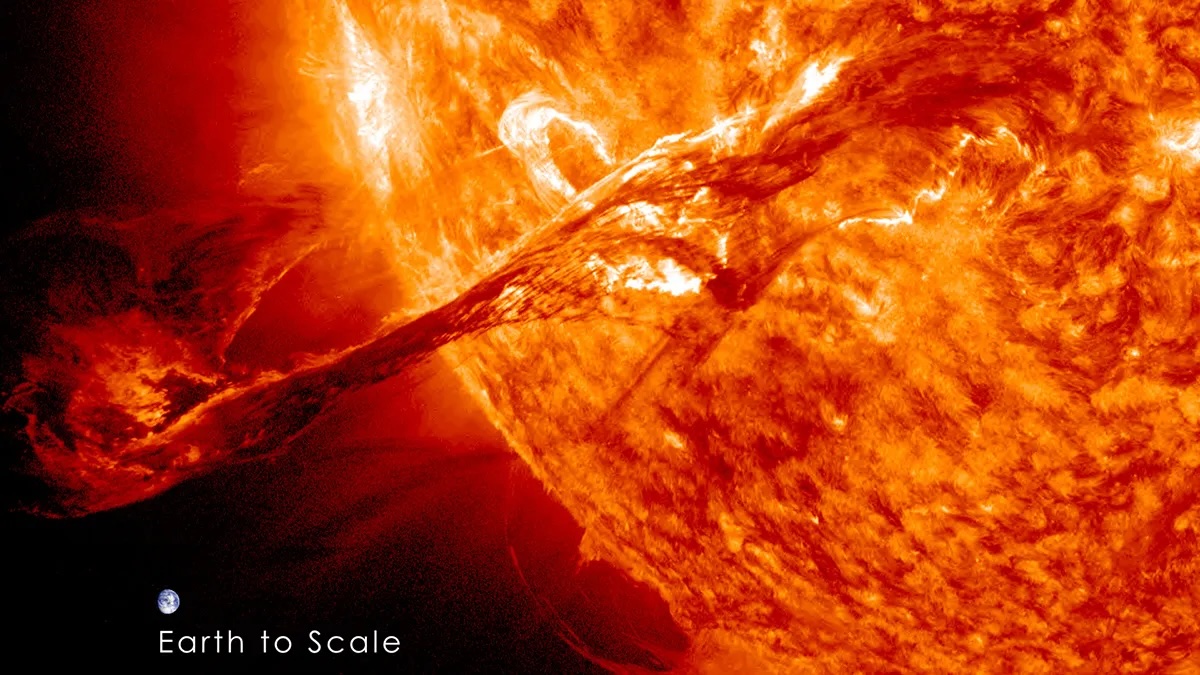

Powerful solar eruption temporarily rips 'tail' off Earth's magnetosphere

A massive disturbance in the solar wind caused Earth’s magnetosphere to fly without its usual tail.

Like a supersonic jet being blasted with high-speed winds, Earth is constantly being bombarded by a stream of charged particles from the Sun known as solar wind.

Just like wind around a jet or water around a boat, these solar wind streams curve around Earth’s magnetic field, or magnetosphere, forming on the sunward side of the magnetosphere a front called a bow shock and stretching it into a wind sock shape with a long tail on the nightside.

Dramatic changes to the solar wind alter the structure and dynamics of the magnetosphere. An example of such changes provides a glimpse into the behavior of other bodies in space, such as Jupiter’s moons and extrasolar planets.

RELATED: Rare, mystery blasts from sun can devastate the ozone layer and spike radiation levels on Earth

Chen et al. report unprecedented observations of a rare phenomenon created during a coronal mass ejection (CME). CMEs typically travel faster than the Alfvén speed, the speed at which vibrating magnetic field lines move through magnetized plasma, which can vary with the plasma environment. A CME in 2023 disrupted the normal configuration of Earth’s magnetosphere for about 2 hours. The researchers analyzed observations from NASA’s Magnetospheric Multiscale Mission (MMS) to learn about what occurred.

On 24 April 2023, the MMS spacecraft observed that though the streaming speed of the solar wind was fast, the Alfvén speed during the strong CME was even faster. Typically, solar wind travels faster than Alfvén speed. This anomaly caused Earth’s bow shock to temporarily disappear, allowing the plasma and magnetic field from the Sun to interact directly with the magnetosphere. Earth’s wind sock tail was replaced by structures called Alfvén wings that connected Earth’s magnetosphere to the recently erupted region of the Sun. This connection acted as a highway transporting plasma between the magnetosphere and the Sun.

The unique CME event offered new insights into how Alfvén wings form and evolve, the authors write. A similar process could occur around other magnetically active bodies in our solar system and universe, and the researchers’ observations suggest the formation of aurorae on Jupiter’s moon Ganymede may also be attributable to Alfvén wings. The authors suggest future work could look for similar Alfvén wing aurorae occurring on Earth. (Geophysical Research Letters, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024GL108894, 2024)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This article was originally published on Eos.org. Read the original article.

Nathaniel Scharping is a contributing writer for Eos.org.