Enormous explosions may be visible on the sun during the April 8 solar eclipse

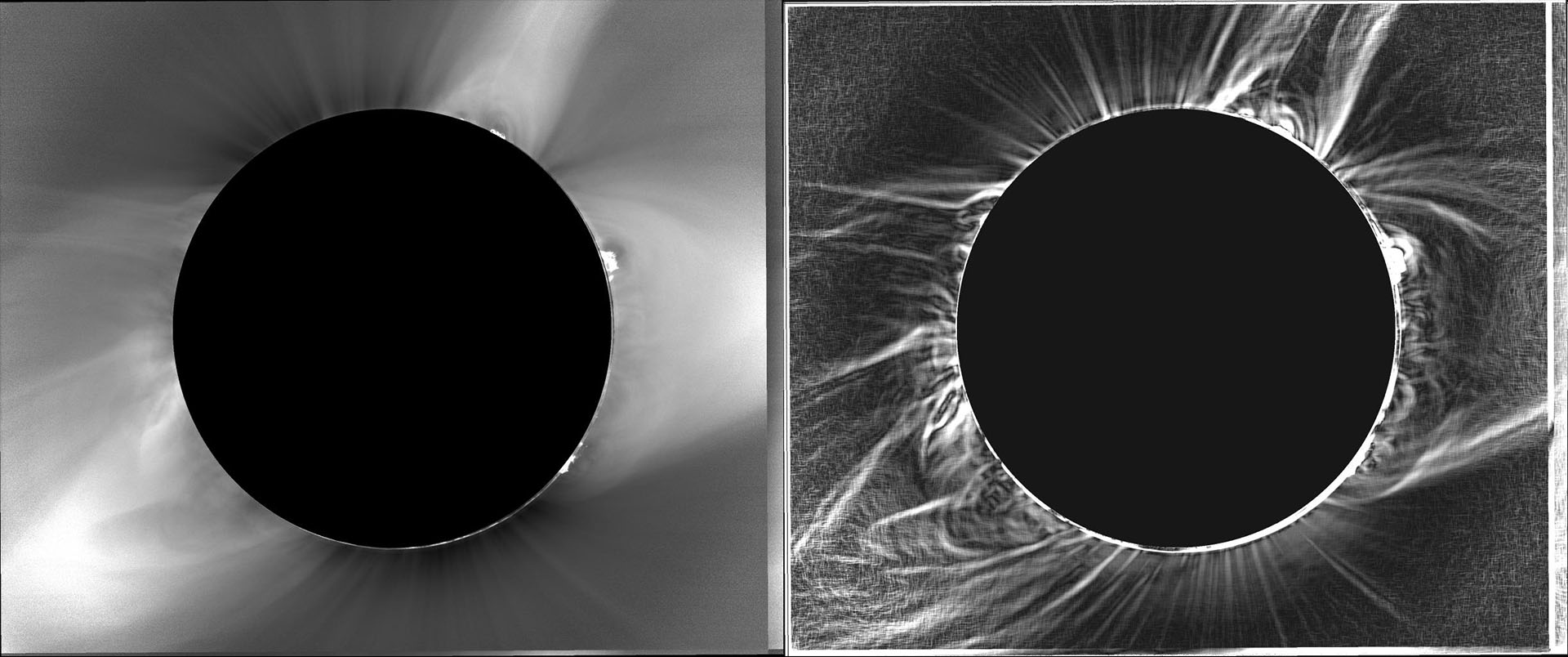

When the moon fully covers the sun on April 8, viewers will have a rare view of the sun's corona, and everything that explodes out of it.

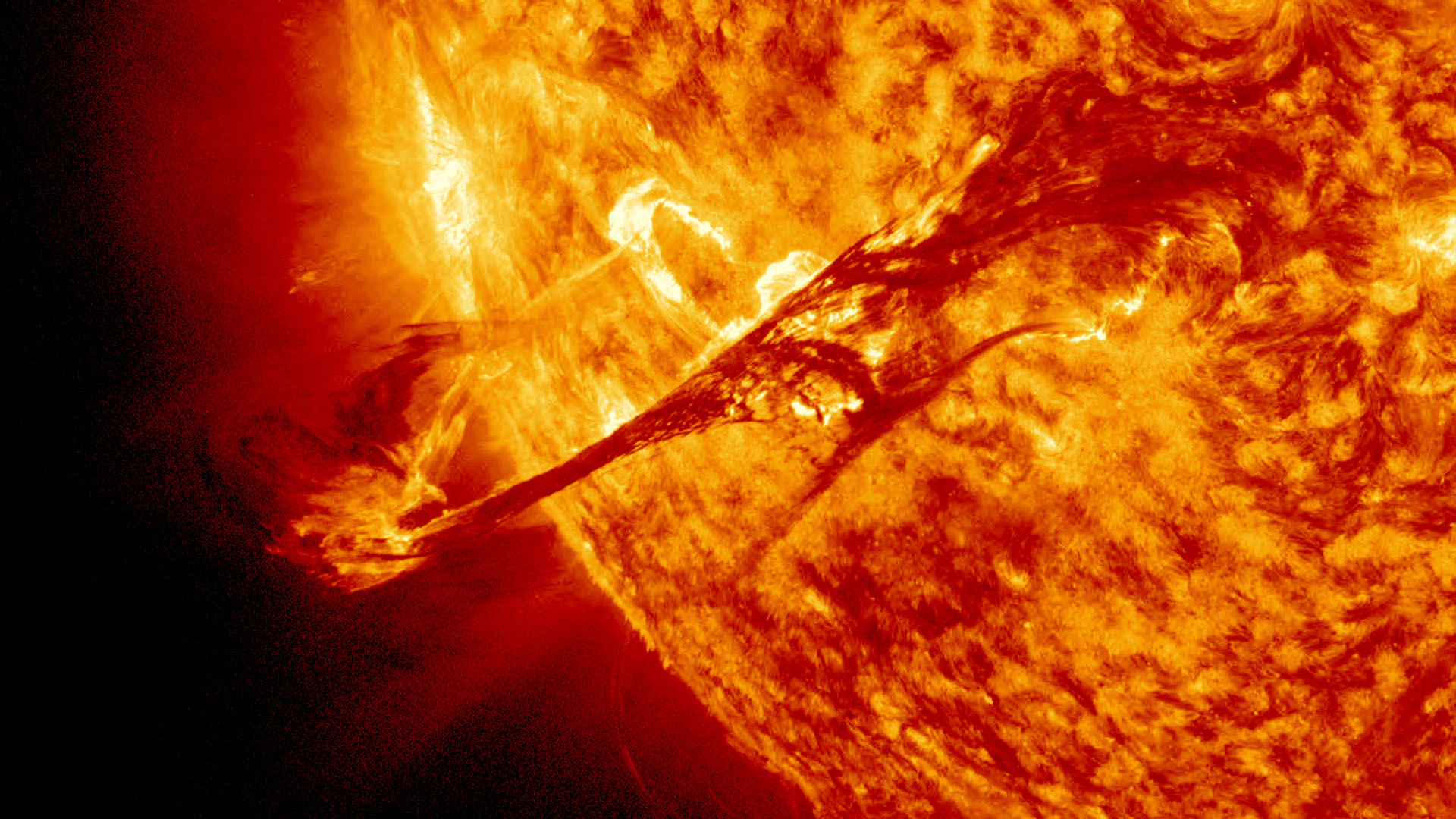

If you're in the path of totality for the April 8 total solar eclipse, you'll experience a brief period of darkness — totality — for a few seconds or minutes. This is the only safe time to look directly at the sun without solar eclipse glasses. If you observe the sun's corona during totality, you may see dark-pink towers and loops of electrically charged plasma stretching many times the diameter of Earth into space. During the last total solar eclipse, in Australia on April 20, 2023, these "prominences" were spectacular — and vast.

These prominences will almost certainly be on show during totality in North America on April 8, because the sun is likely at the peak of its 11-year solar cycle, known as solar maximum.

Prominences can be visible for days — you can look at them anytime you want, if you use a hydrogen alpha telescope — but there are a couple of other rare phenomena you might be able to witness during totality. Here's what solar activity to look for during the total solar eclipse.

Related: What's the longest solar eclipse in history? (And how does the April 2024 total eclipse compare?)

Coronal mass ejections

One such phenomenon that might be visible is a coronal mass ejection (CME).

"If we get lucky, a CME will present itself as a twisted, spiral-like structure, high in the atmosphere in the sun," Ryan French, a solar physicist at the National Solar Observatory in Boulder, Colorado, and author of "The Sun: Beginner's Guide to Our Local Star (Collins, 2023), told Live Science's sister site Space.com. A CME is a huge ejection of magnetic field and plasma mass from the sun's corona. It moves fast but looks stationary over a few hours.

"What this does mean, however, is that the same eruption could be seen in Rochester as it was in Dallas, at different stages of the same long-duration eruption," French said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It will take 100 minutes for the moon's shadow to cross North America, so a CME could go off just before and be visible to everyone under a clear sky.

CMEs can certainly happen during totality. One was imaged on Dec. 14, 2020, during the "Great Patagonian Eclipse" in Chile, when the sun was close to solar minimum.

Solar flares

Solar flares are powerful bursts of radio waves, visible light, X-rays and gamma-rays at the surface of the sun that travel at light speed and take just eight minutes to reach Earth. They often follow a CME.

Although three solar flares that reached X class — the highest-intensity level —went off during one week in February, it's highly unlikely that one will be seen during totality.

Frequency: Multiple times a month

Duration: A few minutes

Appearance: Red loops close to the sun's surface

"A solar flare is different to a CME — it's located far lower in the sun's atmosphere, closer to the moon's edge, and would be visible for only a few minutes," French said. "These would appear similar to low-altitude prominences, visible as red loops closer to the sun's surface."

However, the timing and position of a solar flare and a CME would have to be just right. "To be visible from Earth, it needs to be located above the sun's edge — so as not to get blocked by the moon — during the few minutes of totality," French said.

"Giant eruptive prominences"

We'll see prominences during totality on April 8. "Prominences come in a large range of sizes and are more common during solar maximum," French said. "Sometimes prominences erupt, untethering from the sun's surface and expanding into the solar system."

That would be a spectacular sight, but what eclipse chasers really want to see are "giant eruptive" prominences — preferably detached from the sun's surface and free-floating in the corona.

"There have been a few examples of such prominence eruptions over the past few months, each of which would have given a great show if occurring during a total solar eclipse," French said. "But it's worth noting that the eclipse will still provide a view of stationary, non-eruptive prominences; they'll just be smaller and closer to the sun's surface than they would be mid-eruption."

Extending totality to view more eruptions

"The problem with eclipses is that they only last a few minutes, so you can't usually take measurements over time," Amir Caspi, principal scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, told Space.com. "However, the sun is incredibly dynamic; some processes take minutes or even seconds, such as a solar flare or a CME," Caspi said.

Given that it's unlikely that such brief events will occur during totality, there's only one solution: to make totality longer. One way to extend it is to get in a supersonic jet and chase the moon's shadow. Scientists did that in 1973 using Concorde, achieving a 73-minute totality.

The alternative is to film the eclipsed sun for a few minutes from across an entire continent, hoping that someone, somewhere, will catch the beginning or end of an event. That rarely happens, but it will on April 8. That day, totality will arrive in the U.S. in Texas at 1:27 p.m. CDT and leave in Maine at 3:35 pm EDT — a total of 68 minutes.

The Citizen Continental-America Telescopic Eclipse (CATE 2024) project, which Caspi leads, is an attempt to make a continuous 60-minute 3D movie of the sun's corona in polarized light, using 35 teams of three or four citizen scientists. Each will use standardized cameras and setups and hope to get lucky with the sun.

Originally posted on Space.com.

Jamie Carter is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor based in Cardiff, U.K. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners and lectures on astronomy and the natural world. Jamie regularly writes for Space.com, TechRadar.com, Forbes Science, BBC Wildlife magazine and Scientific American, and many others. He edits WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com.