Space photo of the week: The sun's violent corona like it's never been seen before

The sun's outer atmosphere was captured at previously impossible extreme ultraviolet wavelengths thanks to a last-minute engineering hack.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

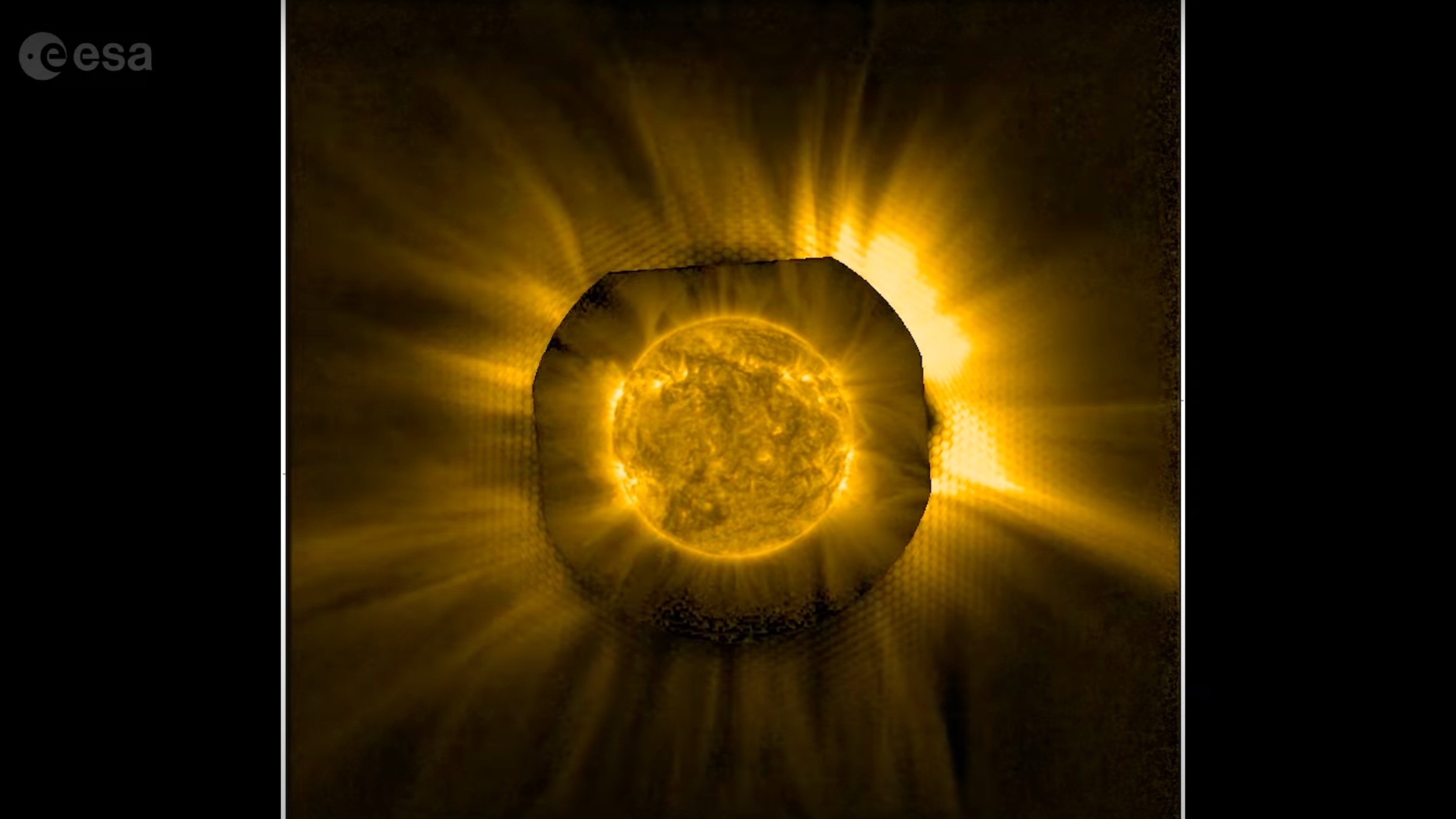

What it is: The sun's outer atmosphere, as captured by the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) on Solar Orbiter, a European Space Agency (ESA) spacecraft developed in collaboration with NASA.

Where it was taken: Halfway to the sun

Why it's so special: As this video shows, Solar Orbiter captured part of the sun's hotter outer atmosphere, its corona, that had been impossible for it to image until now.

The corona is a million times fainter than the glare from the sun's bright surface (the photosphere), which typically keeps it hidden. However, the corona's temperature is around 1.8 million degrees Fahrenheit (1 million degrees Celsius), 150 times hotter than the photosphere — a mystery that has long baffled scientists. Because the corona produces the solar wind — charged particles that flood the solar system and can damage satellites and power grids — it's vital for scientists to understand this part of the sun.

The video is actually a composite of data from two spacecraft. The image of the sun's disk comes from NASA's STEREO spacecraft, which just happened to be looking at the sun from almost the same direction as Solar Orbiter at the same time. It's superimposed over a wider ultraviolet image of our star's corona taken using Solar Orbiter's EUI.

However, the EUI was able to image the corona only because, just before launch, an engineer decided to add a small "thumb" to the camera's shutter. When the shutter is half-open, the thumb just covers the sun's disk, leaving only the corona in view.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It was really a hack," Frédéric Auchère, an astronomer at the Institut d'Astrophysique Spatiale in France and a member of the EUI team, said in a statement. "I had the idea to just do it and see if it would work. It is actually a very simple modification to the instrument."

Simple, but brilliant. Solar Orbiter already has a coronagraph — an instrument that blocks the sun's surface to reveal the corona — called Metis. But the last-minute "hack" allowed the corona to be imaged much deeper into a region of the sun's atmosphere that's rarely been explored.

"Physics is changing there, the magnetic structures are changing there, and we never really had a good look at it before," EUI principal investigator David Berghmans, of the Royal Observatory of Belgium, said in the statement. "There must be some secrets in there that we can now find."

Solar Orbiter, which launched in February 2020, has six ultraviolet telescopes that are now taking the first observations from close to the sun.

Jamie Carter is a Cardiff, U.K.-based freelance science journalist and a regular contributor to Live Science. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners and co-author of The Eclipse Effect, and leads international stargazing and eclipse-chasing tours. His work appears regularly in Space.com, Forbes, New Scientist, BBC Sky at Night, Sky & Telescope, and other major science and astronomy publications. He is also the editor of WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus