We are fast approaching the sun's 'battle zone' — and it could be even worse than solar maximum, experts warn

Space weather experts warn that solar activity will persist or even increase after solar maximum has ended and we enter a phase of the solar cycle dubbed the "battle zone."

Solar maximum has only just officially begun. But now, some scientists are warning that the sun's activity won't actually peak until after this explosive phase is over and we enter the solar "battle zone."

This relatively understudied phase of the solar cycle, where giant coronal holes emerge on the sun, could end up being disastrous for Earth-orbiting satellites, which have exponentially multiplied since the last solar cycle, experts warn.

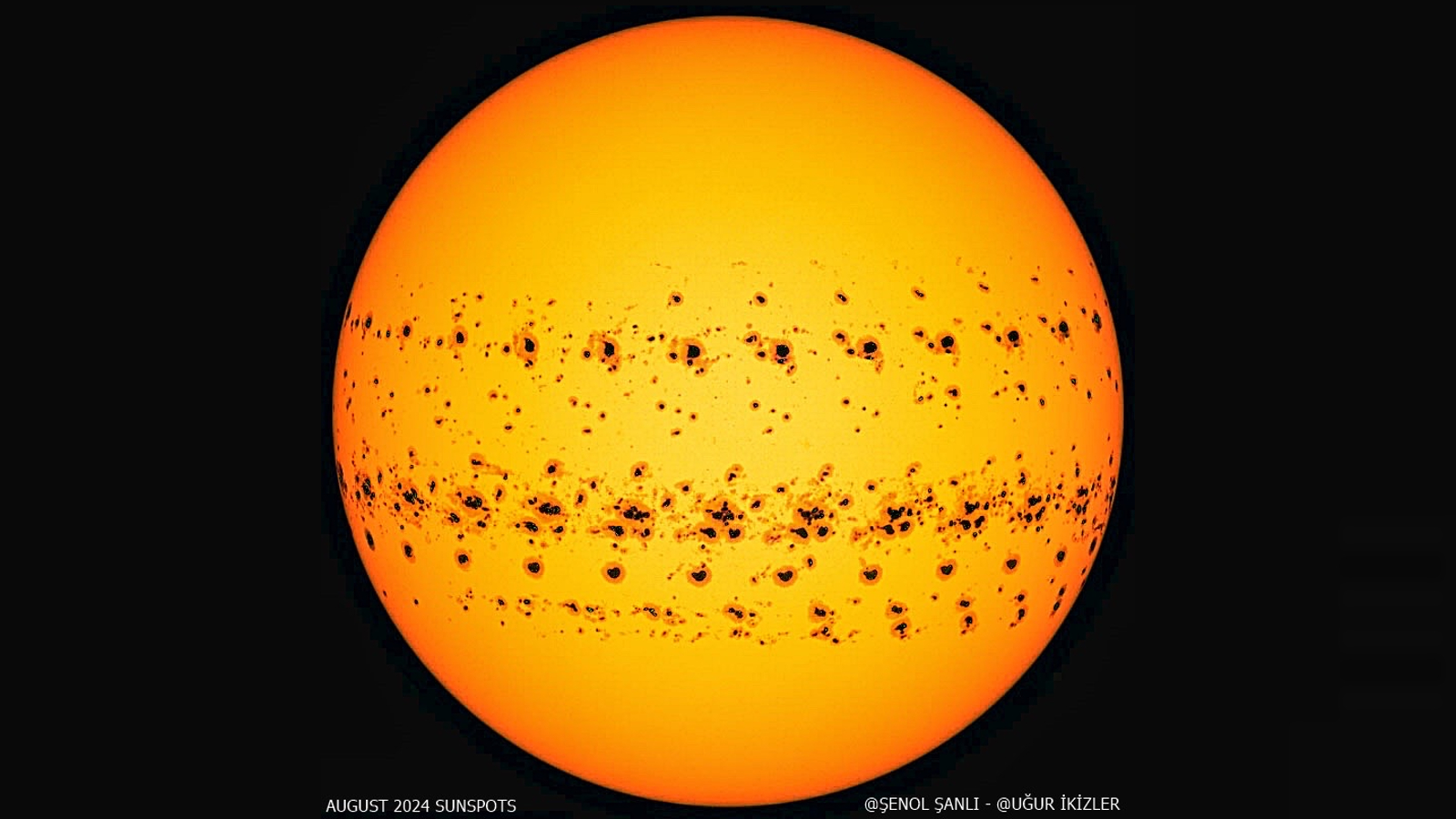

Solar maximum is the period of the sun's roughly 11-year solar cycle, or sunspot cycle, when the number of visible dark patches on the sun peaks. During this time, powerful solar flares explode from the solar surface and hurl clouds of charged particles at Earth, triggering intense geomagnetic storms that paint vibrant auroras across the night sky. Halfway through this period, the sun's magnetic field completely flips, leading to an eventual reduction in sunspots and solar activity until we reach "solar minimum" and the next solar cycle begins.

Solar activity has been ramping up over the last few years, hinting that solar maximum could arrive sooner and be more active than scientists initially expected. Last month, space weather experts confirmed this was the case when they announced that solar maximum is already well underway, and could last for around a year or more.

Related: 32 stunning photos of auroras seen from space

But on Nov. 15, Lynker Space, a new space weather prediction and solution company that formed earlier this year, released a blog post explaining that a newly realized phase of the solar cycle, known as the battle zone, will likely begin in the next year or two, as solar maximum ends.

Scott McIntosh, a solar physicist and Vice President of Lynker Space, told Live Science that geomagnetic activity in the upper atmosphere could increase by up to 50% during the battle zone, which could last well into 2028. "The potential for large, dangerous geomagnetic storms in the next few years is very real," he said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What is the 'battle zone'?

In addition to the 11-year sunspot cycle that most people are familiar with, the sun also has a longer 22-year "Hale cycle," which is the time it takes for our home star's magnetic field to flip and then flip back again.

During this longer cycle, large bands of magnetism, known as Hale cycle bands, emerge at the sun's poles and slowly migrate toward the sun's equator, independent from the sun's wider magnetic field. A new band emerges in both of the sun's hemispheres during each solar maximum and lasts until the end of the next sunspot cycle, when the bands reach the sun's equator and disappear in what researchers call a "solar terminator" event. This means that during the first half of a sunspot cycle (from solar minimum to solar maximum) there is only one Hale cycle band in each of the sun's hemispheres. But during the second half of a cycle (after solar maximum), there are two bands in each hemisphere.

The overlap of these giant bands is what governs the sunspot cycle, McIntosh explained. When there is only one band in each hemisphere, there is a magnetic imbalance across the sun with weaker magnetic fields near the equator, allowing the number of black spots to increase around our home star's waist, he said.

But when a second band is established, it "reduces the imbalance" and makes it harder for sunspots to form, McIntosh added. "Eventually, over a few years, as the bands march towards the equator the imbalance progressively decreases until the sun can't make any sunspots."

Hale cycle bands have historically been overlooked by most space weather forecasters who rely more on sunspot numbers to predict solar activity. However, some scientists are starting to realize that the magnetic bands are more important than we thought. For example, studying the solar terminator event that preceded the current solar cycle allowed McIntosh and others to correctly predict the arrival of solar maximum when other experts did not.

The battle zone is a new term introduced by Lynker Space to describe the period when two Hale cycle bands are "vying for dominance" in each of the sun's hemispheres, McIntosh said.

"We are using this term to describe the fact that geomagnetic activity is enhanced after sunspot maximum," he added.

'Significantly enhanced' activity

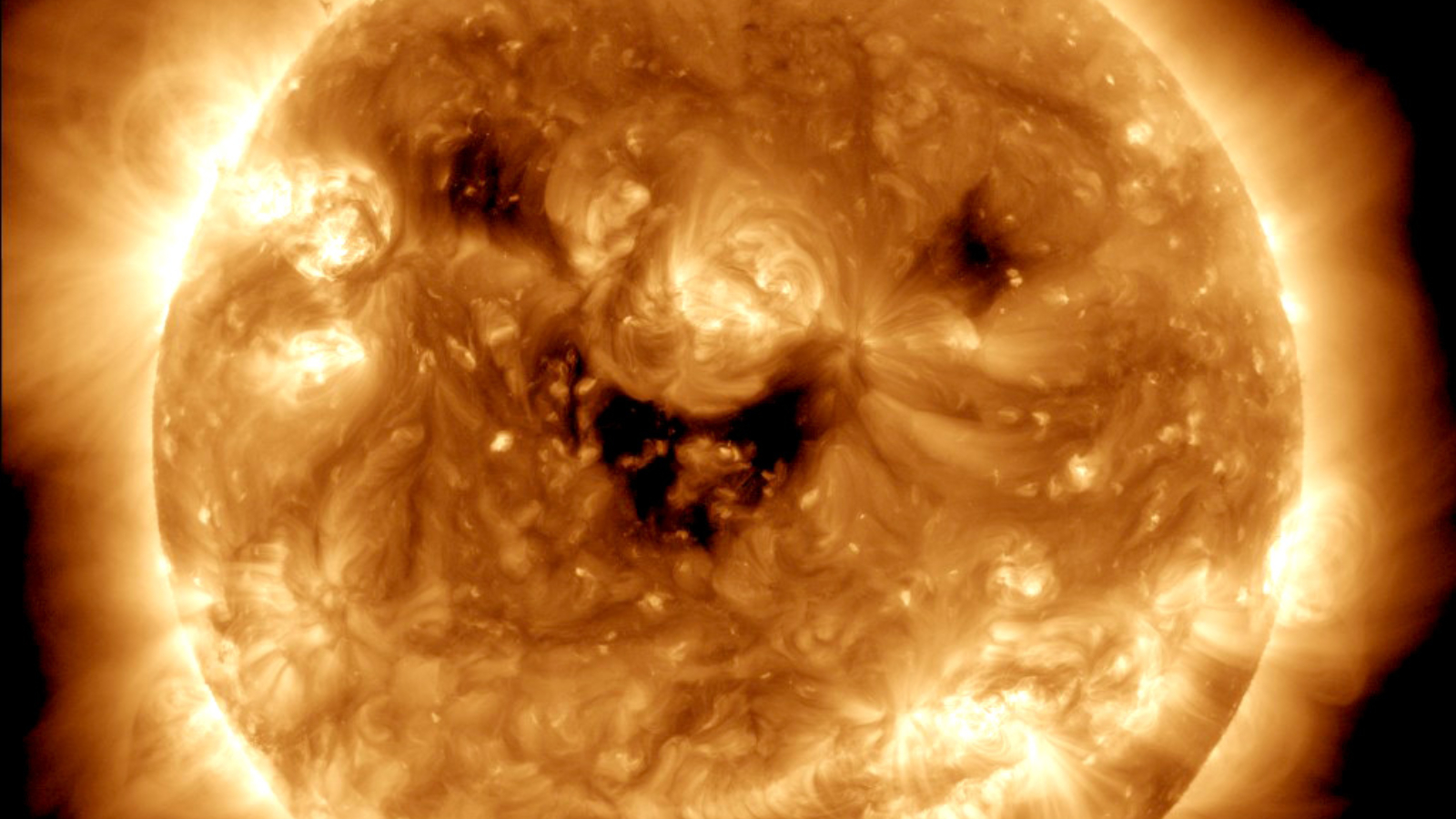

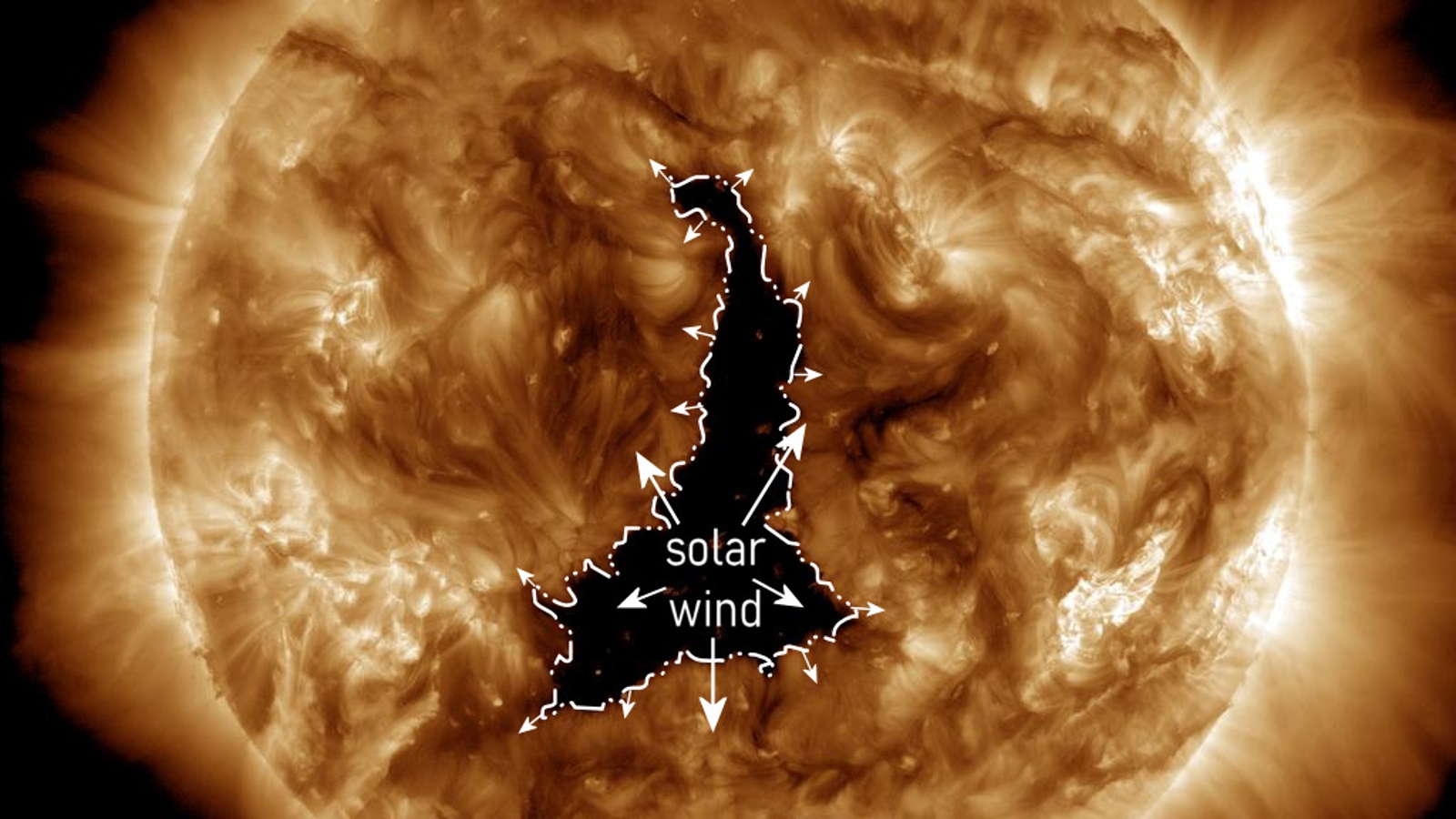

The reason that the battle zone is potentially more dangerous than solar maximum is twofold: First, the number of solar flares erupting from the sun remains high for several years after solar maximum, meaning Earth gets hit by just as many solar storms as we are getting now; second, the magnetic tug-of-war between the Hale cycle bands triggers the formation of coronal holes — giant dark patches created by the sun's magnetic field that poke through the sun's corona, or outer atmosphere.

Coronal holes are dangerous because they can create short and extreme gusts of solar wind — the constant stream of charged particles expelled by the sun. For example, in December 2023, a coronal hole wider than 60 Earths bombarded us with solar wind; and in 2022, a coronal hole created a "gap" in the solar wind, so large that it briefly "blew up" Mars' atmosphere.

All the extra solar particles expelled by coronal holes get soaked up by Earth's upper atmosphere during the battle zone, on top of the particles from the frequently occurring solar storms, which "means that the buffeting of the magnetosphere is enhanced," McIntosh said.

For most people on Earth, the battle zone poses very little threat. It could even be good news for aurora hunters because the chances of seeing the dancing light shows are even higher during this period.

However, this spell could be very difficult for satellite operators because all of this extra geomagnetic activity can cause the upper atmosphere to swell up. When this happens, orbiting spacecraft can experience additional drag, causing them to fall back to Earth — this has already happened during the current solar maximum. With new satellites launching in record numbers thanks to projects like SpaceX's Starlink constellation, the odds of solar weather triggering disastrous satellite malfunctions grow ever higher.

"We have never had so many objects in low-Earth orbit [around 10,000]," McIntosh said. "We will be seeing in real time what the impact of the battle zone is on the businesses fighting to survive and succeed in that environment."

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.