Why I watched the solar eclipse with my kids, a goose and 2,000 trees

A solar eclipse viewing party at Canada's Royal Botanical Gardens peaked with a 90-second totality that blew minds and moved hearts. Also, there were geese.

Hamilton, Ontario — After a nail-biting week of "mostly cloudy" forecasts, the bright sun finally emerged over Hamilton's Royal Botanical Gardens (RBG) just in time for the moon to take a bite out of its side.

The first partial phase of the April 8 total solar eclipse had just begun. A crowd of roughly 100 eclipse chasers, including many young families, had gathered for a viewing event in the garden's arboretum — a rambling, hilly sanctuary of more than 2,200 trees perched above the western tip of Lake Ontario. Solar eclipse glasses in hand, all were hoping for the rare chance to see totality, the fleeting moment when the sun's disk is entirely blocked by the moon and daylight is engulfed by sudden darkness.

If the break in the clouds lasted another hour or so, the garden's human and animal attendants would be treated to nearly 90 seconds of eerie twilight at 3:18 p.m. Birds might cease their singing, a false sunset would wrap around the entire horizon, and bright planets would beam down from the afternoon sky.

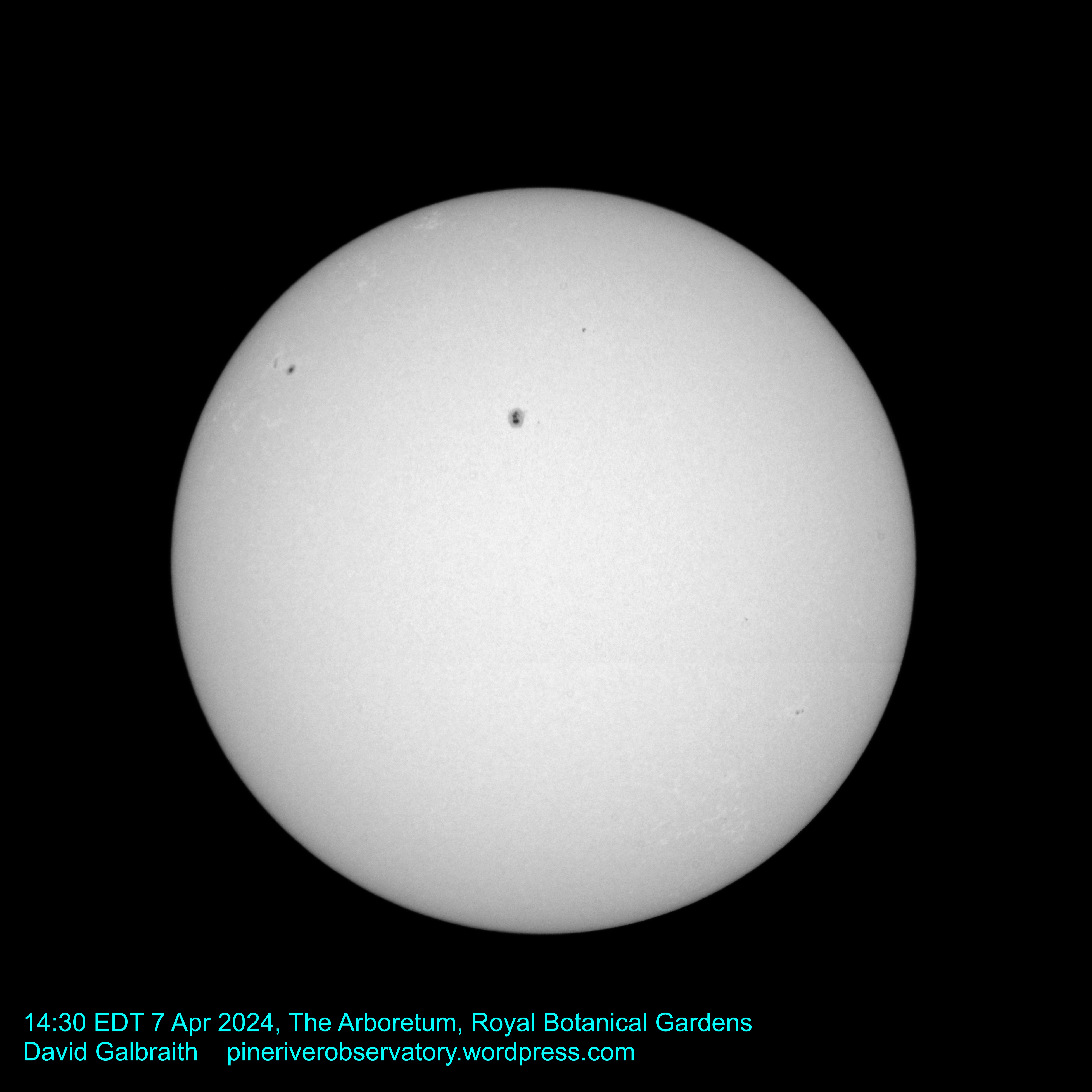

"Every totality is different," David Galbraith, the RBG's Director of Science, explained to a crowd gathered near his solar-filtered telescope. "And Earth is the only planet where it's possible."

With the Earth, moon and sun perfectly aligned, the only trace of our home star would be a thin ring of white light circling the black moon, with jagged tendrils of light spreading into the overbearing darkness. This radiant ring is the sun's corona, its fiery outer atmosphere — although ancient cultures should not be blamed for mistaking it for the wrath of the gods made manifest.

Such a sight would not be visible from this part of North America for another 120 years. The stakes, one could say, were total.

A spot with a view (and a goose)

My family and I chose to view the eclipse from the RBG arboretum not only for the hint of 3 p.m. sunlight predicted in that morning's weather forecast but also for its natural setting — far from the streetlights of Hamilton that would automatically kick on during the darkness of totality. Likewise, we had little interest in braving the heavy traffic to nearby Niagara Falls, where a state of emergency had been declared and more than 1 million eclipse chasers were predicted to descend.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While the arboretum's many oaks, magnolias and cherry trees were still largely leafless at the beginning of April, the site's natural serenity was striking. Moments after arriving, we sighted a hawk coasting nonchalantly over the event's snack table, while squirrels, robins and Canada geese milled about on the hills and trails. We were particularly interested in the potential effects of the eclipse on animals — which have been documented in birds, insects and certain mammals but remain largely mysterious.

We let our 2-year-old lead us to a faraway patch of the garden, high over the water's edge and busy with birds. About 20 minutes before totality, a lone goose flew in from over the lake and stayed near our blanket for the duration of the event. We elected this goose as our eclipse viewing mascot, and I set up my phone to record any possibly anomalous animal sounds that might follow, hoping to share them with NASA.

What it recorded instead was the sheer awe of a family experiencing their first total solar eclipse — something that NASA, I suspect, has little scientific use for.

Countdown to totality

About 10 minutes before totality, the air became noticeably colder as the amount of incoming sunlight plummeted. Gone was the warm spring day; in swept a wintry chill that forced us to put on our jackets and made our breath visible.

A few minutes later, the crisp daylight started to dim. A tattered blanket of high cumulus clouds puttered in from the west. The sun, now just a sliver the size of a crescent moon when viewed through our solar glasses, was still visible through the gauzy patchwork of clouds.

Watching these clouds soon revealed the most bizarre and memorable side effect of the eclipse: the colors of the sky and garden around us began to transform before our eyes.

The blanket of white clouds now looked like bruised, purplish scales. The once-vibrant green of the meadow became duller and distinctly tinged with lavender. Even the air itself seemed to be muddier and murkier. "Everything looks fuzzy," my wife remarked with wonder. The goose, still pecking at the ground nearby, had nothing to say.

This phenomenon, called the Purkinje effect, occurs when our eyes struggle to keep up with sudden shifts in light — an optical illusion that becomes impossible to ignore during the near-instantaneous transformation of day into night during a solar eclipse. Through this altered perception, the garden around us had become a waking dreamscape — leafless trees stretching their violet branches toward the darkening sky.

With less than a minute to go, the movement of the moon became clearly perceptible in our glasses. Its dark form swallowed more of the slim crescent sun every second, until only the barest sliver of light was visible. Finally, hundreds of thousands of miles across space, the last beads of sunlight slipped between the mountains on the moon's edge — and vanished. Totality had begun.

Darkness rushed in, turning the day to twilight. For the next minute and a half, one edge of the moon's immense inner shadow swept over southern Ontario, charging over us at 1,500 mph (2,400 km/h) while simultaneously engulfing parts of Ohio, Pennsylvania and upstate New York.

Related: When is the next total solar eclipse after 2024 in North America?

I removed my eclipse glasses and there, staring back at me, was the corona — a burning white ring around the pitch-black moon, smoldering silently in the false night sky.

Cheers and applause erupted from the nearby crowd, as if Earth, the moon and the sun had just scored a hat trick in a game of cosmic hockey. My wife says she did not intend to cheer so loudly along with the other viewers; the noise just came out of her upon seeing the corona, the way a roller coaster coaxes a scream. Similarly, I do not consciously remember falling to my knees in awe — but the grass stains on my pants afterward suggest that is indeed what happened.

We tried to appreciate the totality of the moment, taking in all the ways the world had suddenly changed. A 360-degree sunset wrapped around the horizon, and streetlights flickered on across the water. Stars were visible in the darkness above, and Jupiter hung brightly to the left of the sun and moon. My 5-year-old son suggested we make a wish upon it. My 2-year-old son asked if it was bedtime.

As our 90-second totality expired, a single bright flash of light began to grow on the trailing edge of the moon. The light grew larger and brighter, creating the iconic diamond ring structure that signals totality is about to end. Reluctantly, we looked away as the face of the sun slowly appeared again.

Through all of this, our goose companion had been silent. Only when the daylight began to filter slowly back in did it let out a honk, met by the tweets of several other birds greeting what they may have imagined was a new dawn.

And, in a way, that's exactly what it was. As the moon's shadow plowed onward toward millions of other eclipse viewers eagerly awaiting their own date with totality, it became clear that a defining experience in our lives had just occurred. My wife, who had been on the fence about attending the day's event after being underwhelmed by past lunar eclipses, instantly pulled out her phone to search for the next total solar eclipse. (Answer: Spain and Iceland in 2026. Perhaps we will see you there — if the stars align.)

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.