Scientists finally know how long a day on Uranus is

An 11-year Hubble study has finally revealed how long a day lasts on Uranus.

A day on Uranus is about half a minute longer than previously thought, according to new research.

An analysis of 11 years of Hubble Space Telescope observations shows that Uranus' day lasts 17 hours, 14 minutes, and 52 seconds. That's 28 seconds longer than NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft estimated when it passed Uranus in 1986. Researchers reported the updated estimate April 7 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Nearly 40 years ago, Voyager 2 became the first spacecraft to observe Uranus up-close. Using radio signals from the planet's auroras and magnetic field data collected by the spacecraft, astronomers at the time found that Uranus' day lasted approximately 17 hours, 14 minutes and 24 seconds.

Researchers used that rotation period to define a coordinate system for the planet. But the measured period came with an inherent uncertainty of about 36 seconds, which gradually added up as each Uranian day passed. Within a few years, the uncertainty made it impossible to accurately determine the orientation of the planet's magnetic axis.

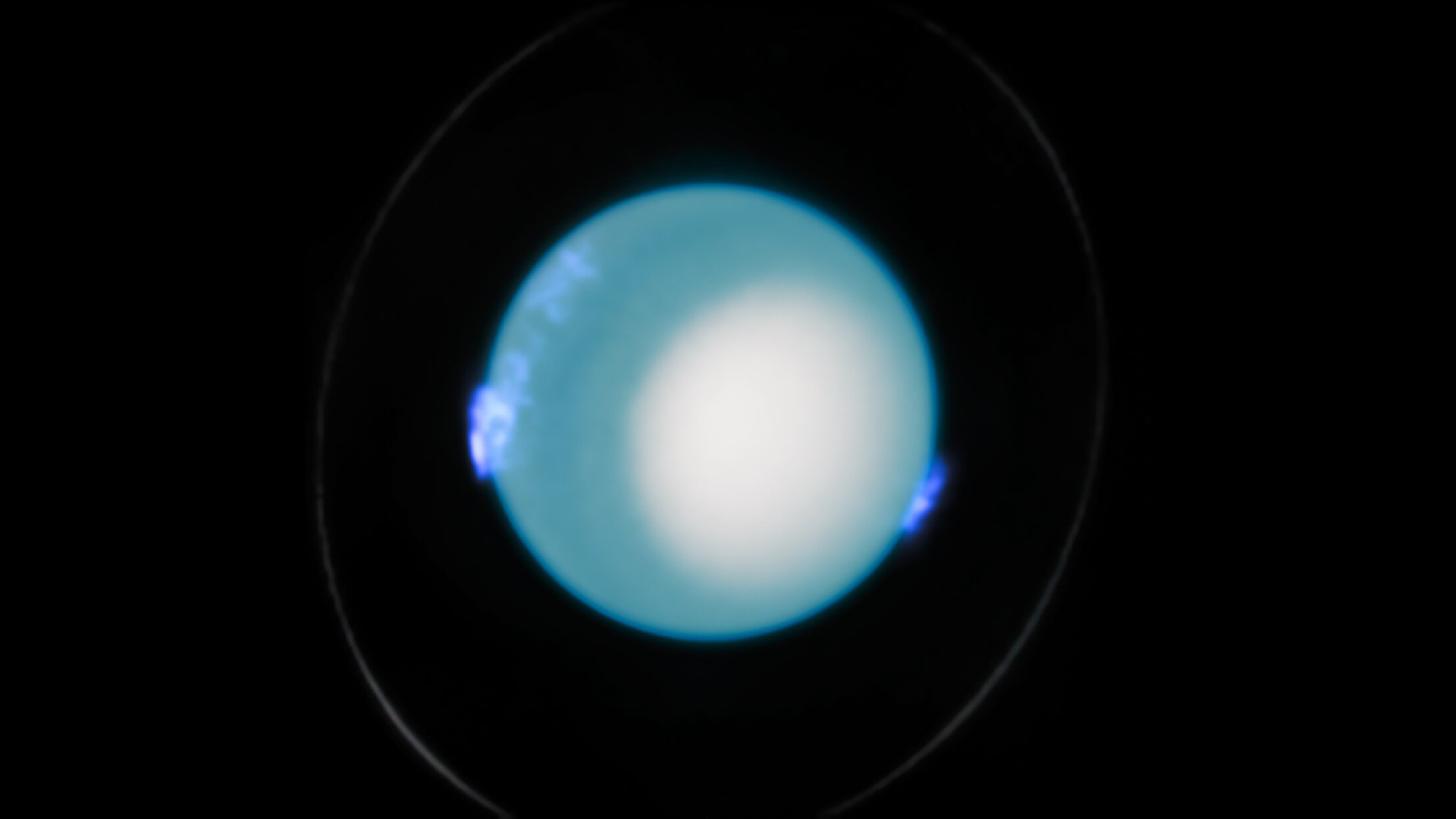

To get more reliable estimates of the planet's rotational period, the authors of the new study tracked the movement of auroras at Uranus' magnetic poles from six sets of Hubble observations taken between 2011 and 2022. This helped them refine the locations of the planet's magnetic poles, which they used to work out a more accurate estimate of Uranus' rotational period. The new measurement has an uncertainty of less than 0.04 seconds, according to the team.

"The continuous observations from Hubble were crucial," first study author Laurent Lamy, an astronomer at the Paris Observatory, said in a statement. "Without this wealth of data, it would have been impossible to detect the periodic signal with the level of accuracy we achieved."

Related: 'Hidden' rings of Uranus revealed in dazzling new James Webb telescope images

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The 28-second difference is within the margin of error of Voyager 2's calculation, but the new duration has a much lower uncertainty. "It's not so much that it's changed," Tim Bedding, an astronomer at the University of Sydney in Australia, told New Scientist. "It's now accurate enough to be more useful."

With this smaller uncertainty, the coordinate system based on the new measurement of Uranus' rotational period should hold up for several decades, the team said. Future missions to Uranus, such as the proposed Uranus Orbiter and Probe, could rely on this coordinate system when selecting an atmospheric entry site, the researchers wrote in the study.

"With this new longitude system, we can now compare auroral observations spanning nearly 40 years and even plan for the upcoming Uranus mission," Lamy said in the statement.

Skyler Ware is a freelance science journalist covering chemistry, biology, paleontology and Earth science. She was a 2023 AAAS Mass Media Science and Engineering Fellow at Science News. Her work has also appeared in Science News Explores, ZME Science and Chembites, among others. Skyler has a Ph.D. in chemistry from Caltech.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.