We've been wrong about Uranus for nearly 40 years, new analysis of Voyager 2 data reveals

Voyager 2's 1986 flyby of Uranus, the main source of our knowledge of the icy planet, could have come at the same time as a weird plasma burst from the sun.

Our understanding of Uranus could have been wrong for nearly four decades, new research suggests — and a weird space weather event is likely to blame.

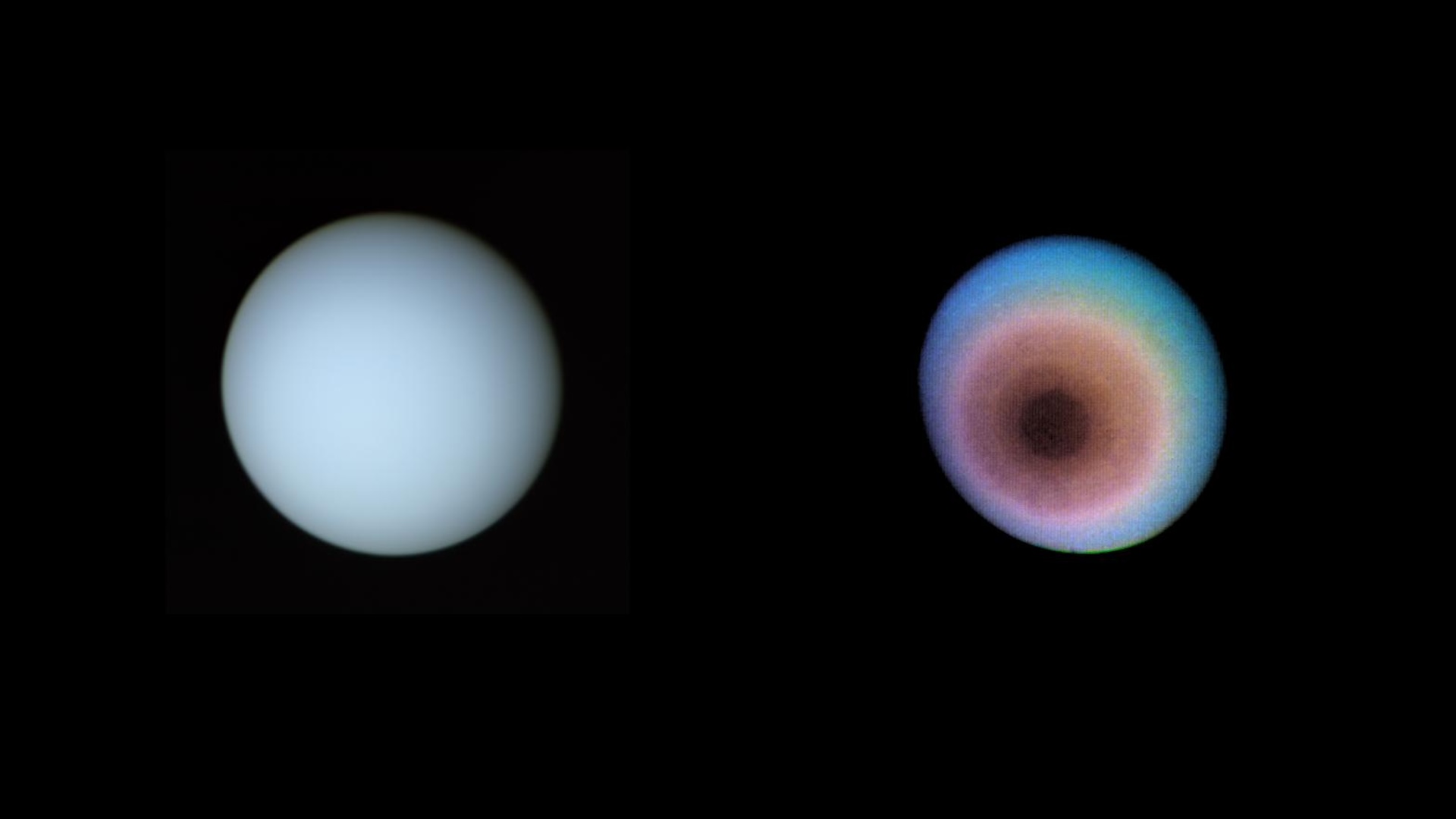

Much of what we know about Uranus is taken from data gathered by NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft, which zipped past the ice giant in 1986. The probe's observations revealed the planet had a bizarrely lopsided magnetic field that is misaligned with the planet's rotation and filled with unusually energetic electrons.

But a new analysis of Voyager 2's data revealed the likely cause of the strange readings: a burst of solar wind that whacked the planet's magnetic field out of shape just before the probe flew by. In other words, our understanding of Uranus may be based on an anomalous snapshot in time, rather than the planet's typical nature. The researchers published their findings Nov. 11 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

"If Voyager 2 had arrived just a few days earlier, it would have observed a completely different magnetosphere at Uranus," study lead author Jamie Jasinski, a space plasma physicist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California, said in a statement. "The spacecraft saw Uranus in conditions that only occur about 4% of the time."

Magnetic fields form around planets thanks to the churning movement of material inside their molten cores, and they shield planets from jets of plasma known as solar wind that are launched from the sun. When solar particle radiation hits a planet's magnetosphere, it gets trapped by magnetic field lines and is shuffled along it into pockets called radiation belts.

Related: Scientists finally know why ultraviolent superstorms flare up on Uranus and Neptune

It was Uranus's radiation belts — alongside its lopsided magnetic field — that baffled scientists when the first readings from Voyager 2 appeared. The planet's magnetosphere was packed with electron radiation belts second in intensity only to Jupiter. But the rest of the field was devoid of plasma, revealing no apparent source that fed the radiation belts.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The deficit of plasma elsewhere also led scientists to conclude that water ions were not being produced by Uranus' five major moons, four of which are encased in ice. This led astronomers at the time to think that these moons were likely geologically inactive and therefore likely lacked hidden oceans.

By reanalyzing the readings in light of the recorded outburst of solar wind, the researchers behind the new study found that, just before Voyager 2's flyby, the solar wind drove the typical plasma out of Uranus' magnetosphere, knocking it temporarily out of shape and injecting electrons into its radiation belt — similar to how Earth's magnetic field becomes charged-up and warped when hit by intense solar storms.

"The flyby was packed with surprises, and we were searching for an explanation of its unusual behavior," Linda Spilker, a senior research scientist at the JPL who was involved in the Voyager 2 mission, said in the statement. "The magnetosphere Voyager 2 measured was only a snapshot in time. This new work explains some of the apparent contradictions, and it will change our view of Uranus once again."

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.