Mysterious flashes on Venus may be a rain of meteors, new study suggests

Bright flashes in the clouds of Venus once thought to be lightning strikes may have a cosmic origin.

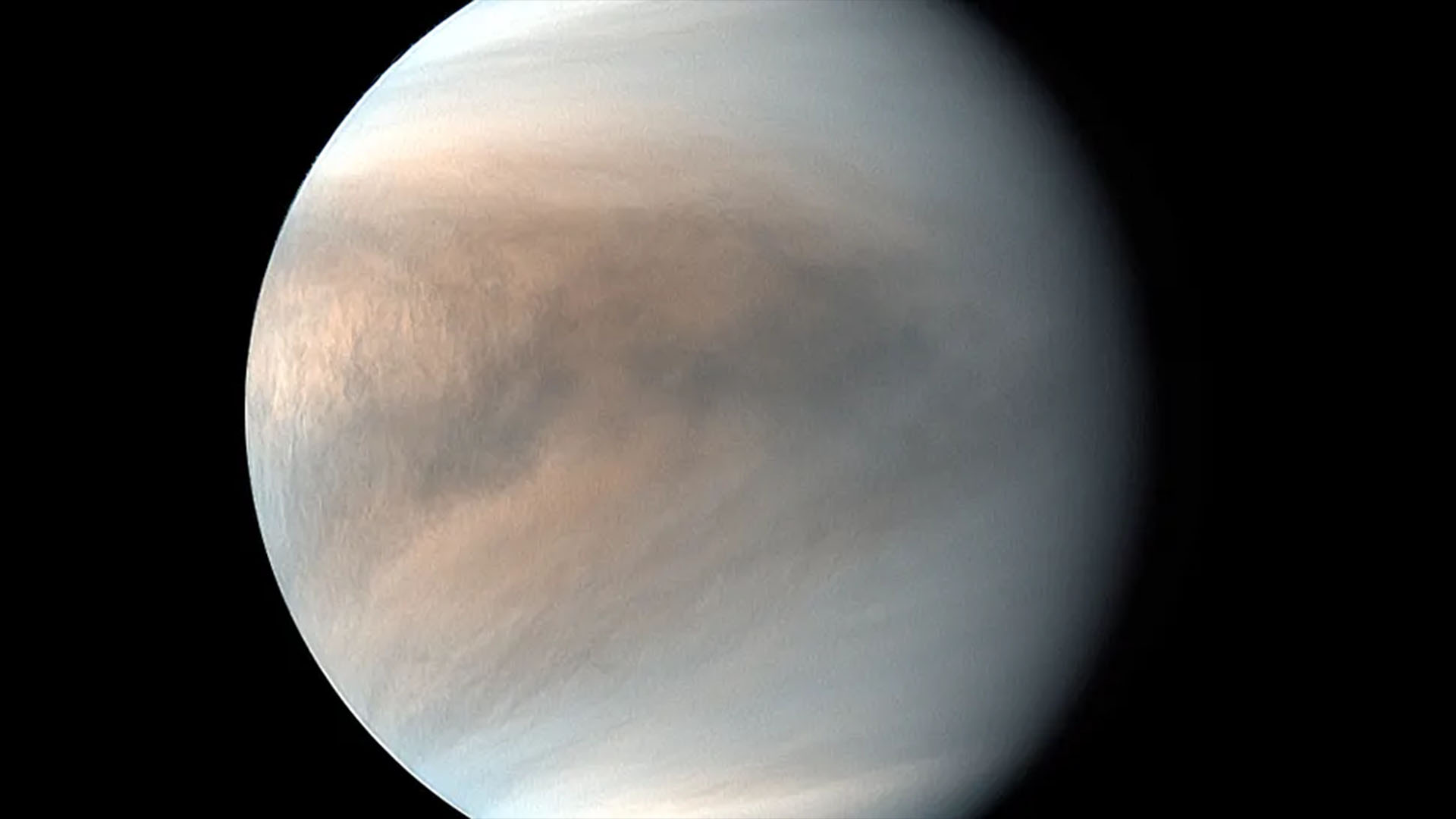

The thick, acid-rich clouds of Venus continue to shroud the planet next door in mystery.

Scientists have long-debated whether intriguing light flashes recorded by previous Venus missions are evidence of lightning strikes on the planet. If those flashes really represent lightning, future missions to the windy planet need to be designed such that they are strong enough to survive the bolts, which are known to damage electronics here on Earth.

Moreover, lightning on Venus means Earth's cosmic neighbor would join the rare planetary club whose current members — Earth, Jupiter and Saturn — host lightning bolts in their clouds. Such flickers of light would also be unique on the world in that they'd exist despite Venus' clouds lacking water, a substance considered key in creating electrical charges.

Related: Mirror-like exoplanet that 'shouldn't exist' is the shiniest world ever discovered

So, scientists are excited by the possibility of lightning on Venus — but the evidence so far has been circumstantial at best.

And now, a new study suggests lightning might be extremely rare on the planet. Instead, it offers the possibility that meteors burning up high in Venus' atmosphere are very likely responsible for the detected light flashes.

Assuming there'd be a similar number of meteors raining on Venus as seen on Earth, the team estimated the number of flashes these space rocks should cause. The researchers then compared that data to the flashes recorded in the planet's atmosphere by two surveys: The Mt. Bigelow Observatory in Arizona and Japan's Venus orbiter Akatsuki, which has been circling our planetary neighbor since 2015.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Results showed that space rocks burning up about 62 miles (100 km) from Venus' surface "may be responsible for most or even possibly all of the observed flashes," according to the study. "Lightning thus does not seem like a threat to missions that pass through or even linger within the clouds."

Data from previous Venus missions by the U.S., Europe and the former Soviet Union included signals that scientists have long interpreted as lightning strikes, and suspected they even occur more frequently than those that flash on Earth.

In the recent past, however, both the Saturn-bound Cassini and the sun-bound Parker Solar Probe "searched for but failed to find radio signals from lightning" on Venus, researchers wrote in the new study.

Studies like this are important for planning future missions to Venus, an effort that is widely considered long overdue, especially as the recent detection of a possible active volcano on the planet's surface shows the world may still be geologically active.

If lightning strikes are really a risk, probes that attempt to descend to the surface of Venus or those that will float for months in its thick atmosphere will need protection while gathering valuable data.

While there may still be lightning at the surface caused by volcanic eruptions, the new study finds that overall, it is not of significant concern to future missions.

Future probes that descend quickly through Venus' atmosphere are safe, researchers say. That includes NASA's DAVINCI (short for Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble Gases, Chemistry, and Imaging), which is scheduled to plunge through the planet's atmosphere in early 2030s.

For long-lived aerial platforms that hover in the planet's clouds for about 100 Earth days or more, the study finds that a lightning strike is more likely to occur if the probe is within 56 miles (90 km) from the surface.

"However, perhaps such a moderately distant strike would seem more exciting than dangerous," according to the new study.

This research is described in a paper published Aug. 25 in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

This edited article is republished from Space.com under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Space.com, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social