Statue of Liberty blueprints discovered, showing last-minute changes

Originally, Lady Liberty's arm was designed to be more robust.

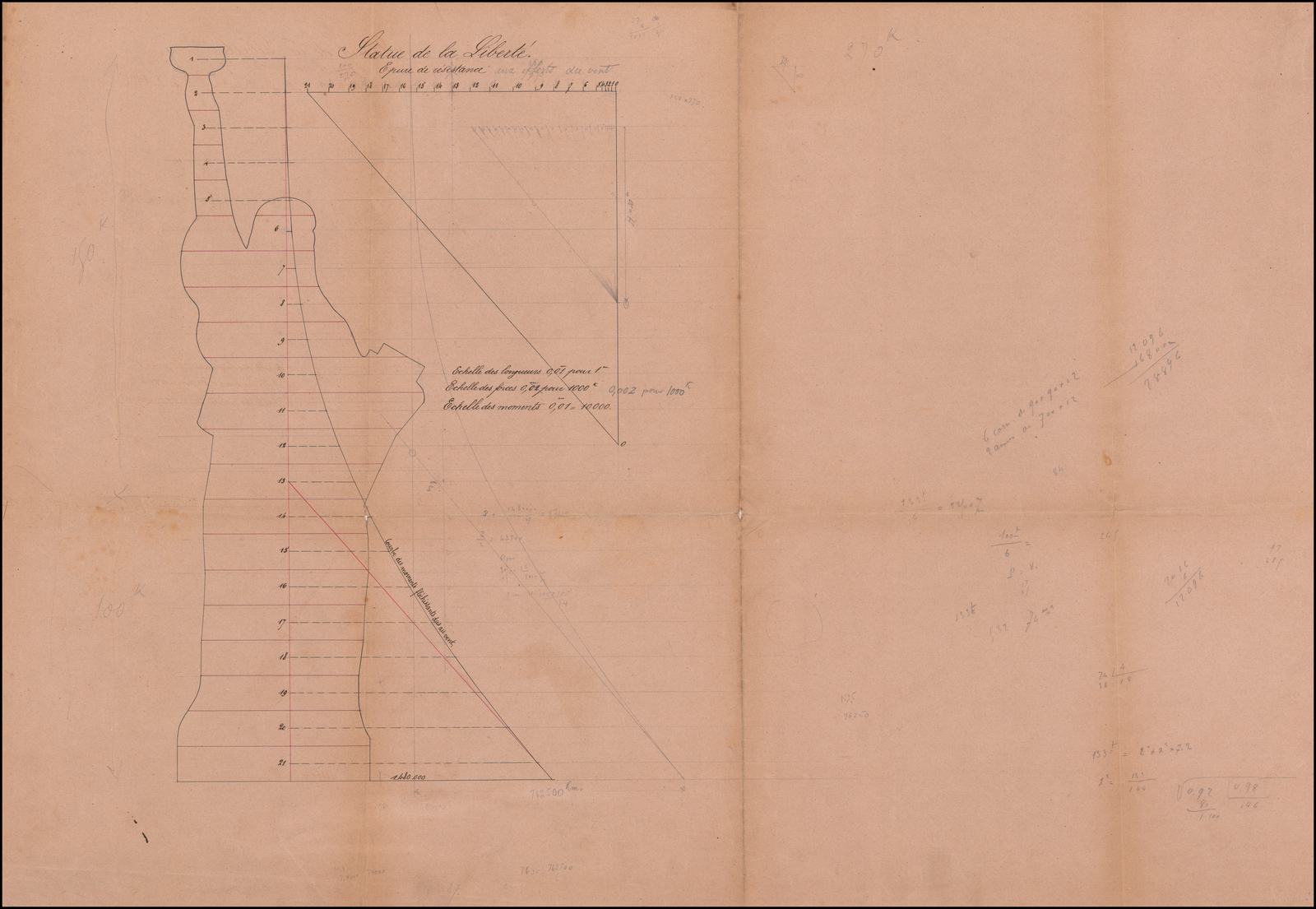

The Statue of Liberty is famous for her torch-bearing arm, but newly discovered blueprints reveal that this arm was revised to be more slender at the last minute, changing the plans of the French engineer Gustave Eiffel who helped design the statue.

Eiffel, of course, is famous for his tower in Paris. But he also determined how to make the already drawn design of the Statue of Liberty structurally sound; that was no easy feat given that New York Harbor experiences ferocious winds.

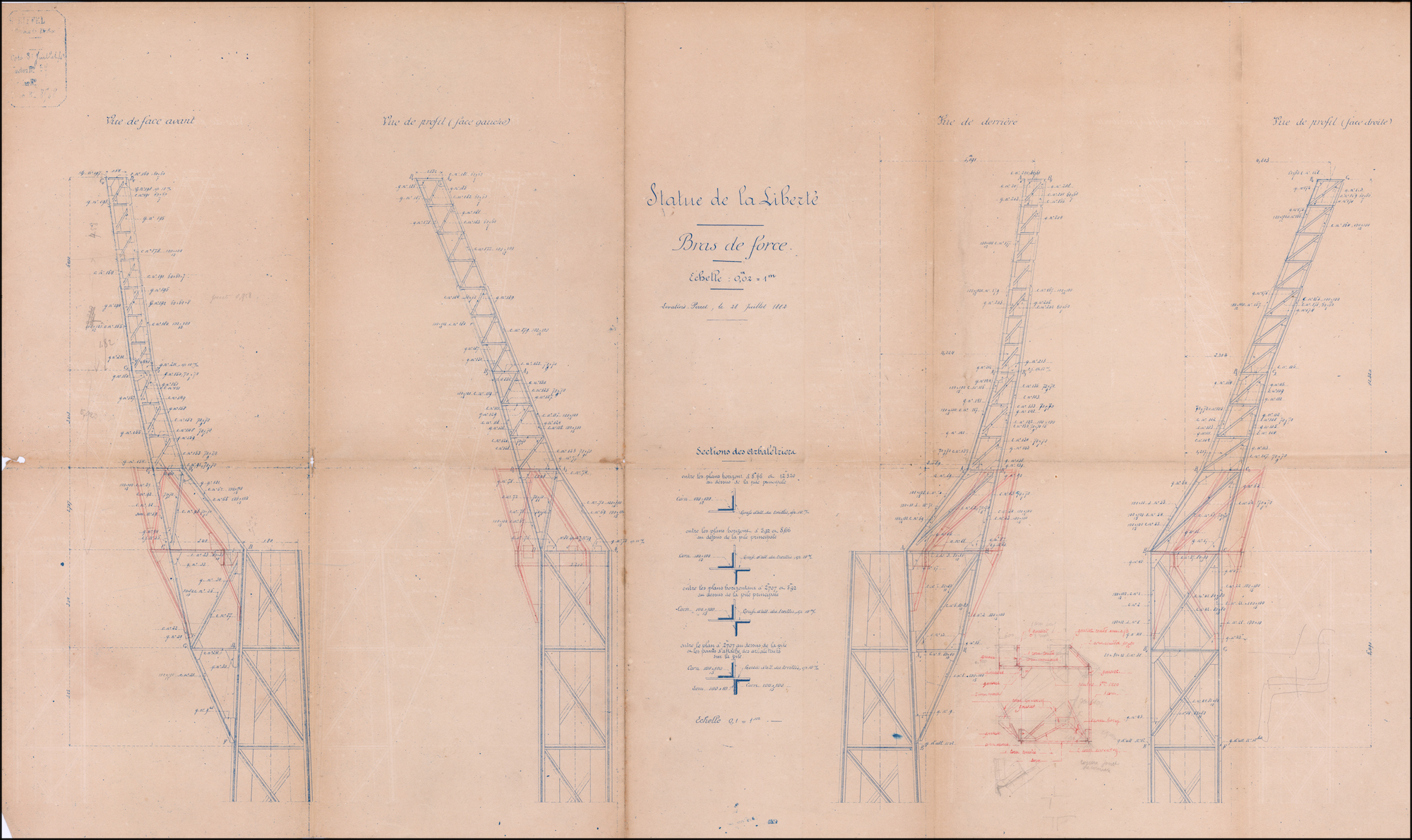

The newly analyzed blueprints show that Eiffel originally designed Lady Liberty's arm to be more robust and vertical — in a word, sturdier — than it is today, according to Smithsonian magazine, which first covered the story. But the blueprints reveal that someone else, perhaps the statue's sculptor, Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi, went in with red ink and revised the arm to be more slender and tilted, making it more aesthetically pleasing, but also more fragile.

Related: 19 of the world's oldest photos reveal a rare side of history

Paris auction

The blueprints were brought to light when, in 2018, California map dealer Barry Lawrence Ruderman bought a folder of Eiffel's historic papers at an auction in Paris. According to the auction catalog, the papers included blueprints for the Statue of Liberty, a unique prize because there are only two other known surviving copies of these blueprints; one is at the Library of Congress and the other is in a private collection in France, according to Ruderman's gallery, Antique Maps Inc.

Inside the folder, Ruderman and Alex Clausen, director of Ruderman’s gallery, found a pile of tightly folded papers that looked too delicate to open without destroying. So, they sent the historic documents to a conservator, who put the papers in a humidified chamber to make them more pliable. The technique worked; Ruderman and Clausen soon found themselves poring over not just blueprints but 22 original engineering drawings of Lady Liberty, many with notes and calculations in the margins.

'"When we first realized what we had, we were awestruck," Ruderman told Live Science in an email. "The Statue of Liberty is quite possibly the most famous modern man-made object on the planet, and we were holding the engineering work that made its public display possible."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A gift from France

The Statue of Liberty was originally intended to celebrate the end of slavery, according to the statue's new museum, The Washington Post reported last year. Only later did the statue turn into a beacon for immigrants, especially with the addition of Emma Lazarus' poem — "Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free" — that was cast onto a plaque and placed inside part of the statue in 1903.

The French poet Édouard de Laboulaye first conceived of the statue. He loved America, but was an abolitionist who raised funds for freed slaves. After the American Civil War, Laboulaye and his fellow abolitionists decided to recognize America's milestone with a gift. Laboulaye commissioned the sculptor Bartholdi to design the statue, which was modeled after the Roman goddess of liberty, according to the National Park Service (NPS).

Bartholdi realized that he needed an engineer to give the copper statue structural integrity. So, he turned to Eiffel. At the time, Eiffel was known for designing railroad bridges, and he used that knowledge to make the statue flexible enough to sway in the wind without toppling over. Even today, Lady Liberty can sway up to 3 inches (7.6 centimeters) and the torch up to 6 inches (15.2 cm) in 50 mph (80 km/h) winds, according to the NPS.

The newly analyzed blueprints show Eiffel's handiwork, including calculations and the iron trusswork designs that would support the Statue of Liberty. Historians have long thought that Bartholdi revised Eiffel's schematic for the statue's arm, and it appears that these blueprints finally give concrete evidence of that, Edward Berenson, a historian at New York University and author of "The Statue of Liberty: A Transatlantic Story" (Yale University Press, 2012), told Smithsonian magazine.

"It looks like somebody is trying to figure out how to change the angle of the arm without wrecking the support," Berenson said.

The revisions are dated to July 28, 1882, after construction for the statue had begun. It's unclear what Eiffel thought of these changes; he had moved onto other projects by that time, and had his assistants act as liaisons with Bartholdi. "That may be one reason why Bartholdi decided he could make modifications, because he knew that Eiffel was not totally hands-on,” Berenson said.

The statue formally opened in 1886. Since then, Lady Liberty's slender arm has posed problems at various times. For instance, in 1916, a German saboteur blew up a munitions depot on a nearby island, a blast that measured the equivalent of a magnitude-5.5 earthquake, Smithsonian magazine reported. This blast caused more than $100,000 worth of damage to the statue, and closed her torch to visitors henceforth.

In the 1980s, engineers suggested fortifying the statue's arm, but preservationists intervened, saying that the statue shouldn't waver from Bartholdi's vision.

To see digital versions of these altered blueprints, visit Antique Maps.

- Climate study: Rising seas could wipe out many cultural landmarks

- Photos: The largest underwater sculpture

- Photos: Hidden monuments found at ancient site of Izapa kingdom

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'How It Works' 'All About Space' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.