Look into the eyes of a Stone Age woman in this incredibly lifelike facial reconstruction

The approximation of the 40-year-old "Penang woman" is "significant."

You can view the virtually reconstructed face of a woman who lived about 5,700 years ago in what is now Malaysia, now that researchers have put a face to a person whose full identity remains a mystery.

A team of archaeologists from the Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM) discovered the skeleton, which they dubbed the "Penang woman," during a 2017 dig at Guar Kepah, a Neolithic site located in Penang, in northwest Malaysia. It was one of 41 skeletons exhumed from the site over multiple excavations. Radiocarbon dating of shells found scattered around the woman's remains revealed that she lived during the Neolithic, or New Stone Age, which spanned from 8,000 to 3,300 B.C. in the region.

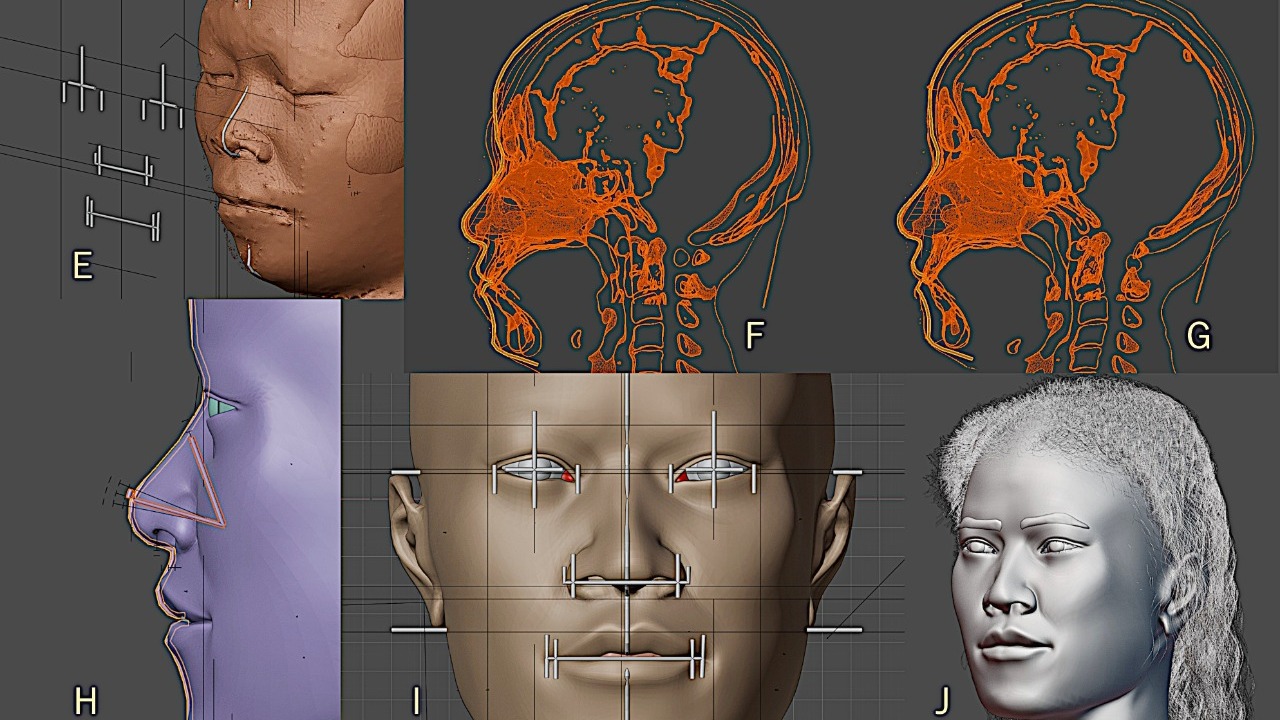

Using CT (computed tomography) scans of the body's "almost complete" skull, as well as 3D imagery of modern-day Malaysians, study co-researcher Cicero Moraes, a Brazilian graphics expert, worked alongside USM researchers to create a facial approximation of the woman, who is believed to have lived until about 40 years old, an estimate based on dental wear and a cranial suture closure.

After digitizing the skull, Moraes put a series of markers along the virtual surface of the skull, "mostly based on statistical studies carried out on compatible populations," such as modern-day Malaysians, Moraes told Live Science in an email. "In addition, we used virtual donors (3D reconstructed computed tomography) with a structure close to the skull to be approximated and we adapted (deformed) the donor until it fit the skull. With all this cross-data, we have an idea of what the face might look like."

Related: Facial reconstruction shows powerful Bronze Age woman's serene expression and huge earrings

That face includes a broad nose and full lips. Moraes described the accuracy of the approximation as "significant," but he cautioned that it's not an exact replica of the woman.

This new information brings archaeologists one step closer to painting a better picture of the woman whose remains were unearthed in one of three shell "middens" (or kitchen dumps, where ancient people would discard shells, bones and other food waste) at the dig site. The woman was found with her arms folded and surrounded by burial goods, including pottery and stone tools, which could indicate that she held an important position in society, according to the Malay Mail, which reported on the dig back in 2019.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Moraes also used what he called the "forensic facial approximation method," which involved measuring the skull and running those numbers through a database to find an individual in the collection with similar facial characteristics.

"We usually take two heads [that contain] the skulls and soft tissues from virtual donors and deform the structures so that the donor skull matches the skull whose face will be approximated," he said. "The result is a face compatible with what it would be like in life."

The total reconstruction process took several months, according to a video by the New Strait Times, an English-language news outlet in Malaysia.

"The final step is to finish the face," Moraes said, which includes adding pigmentation and styling the hair. Currently, researchers are unsure of the cause of the woman's death.

The findings were published Aug. 5 in the journal Applied Sciences.

Originally published on Live Science.

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.