Failed brain surgery and possible human sacrifice revealed in Stone Age burial

A Stone Age skull found in a Spanish cave bears the marks of a failed brain surgery and postmortem decapitation.

The skull, which may have belonged to an adult woman, dates back to approximately 4800 B.C. to 4550 B.C. Archaeologists found the skull deep inside Dehesilla Cave on the Iberian peninsula, alongside a second adult skull — perhaps from a man — and the remains of a young goat, they reported Aug. 13 in the journal PLOS ONE.

The morbid and unusual discovery raises the possibility that the bones were brought to the cave for some sort of religious ritual, study author Daniel García-Rivero, an archaeologist at the University of Seville in Spain, wrote in the paper. One or both of the individuals may have even been victims of human sacrifice.

Related: 25 grisly archaeological discoveries

Strange grave

Dehesilla Cave is a set of caverns in Spain's Baetic Mountains. Stone Age artifacts were found near the mouth of the cave in the 1970s, but the new discovery comes from Room 4, one of the deepest caverns in the system.

There, a 2017 excavation revealed two jawless skulls, buried alongside stone tools, bits of pottery and most of the skeleton of a sheep or goat that was likely less than 10 days old at death. The cave also contained a stone altar and an ash-rich circle, apparently the remains of a 7,000-year-old fire.

It's difficult to determine the sex of an individual from a skull alone, but the size and shape of the skulls suggested that one might have been female and the other male. Both were adults, but it was not possible to pinpoint their ages precisely.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Related: 25 cultures to practice human sacrifice

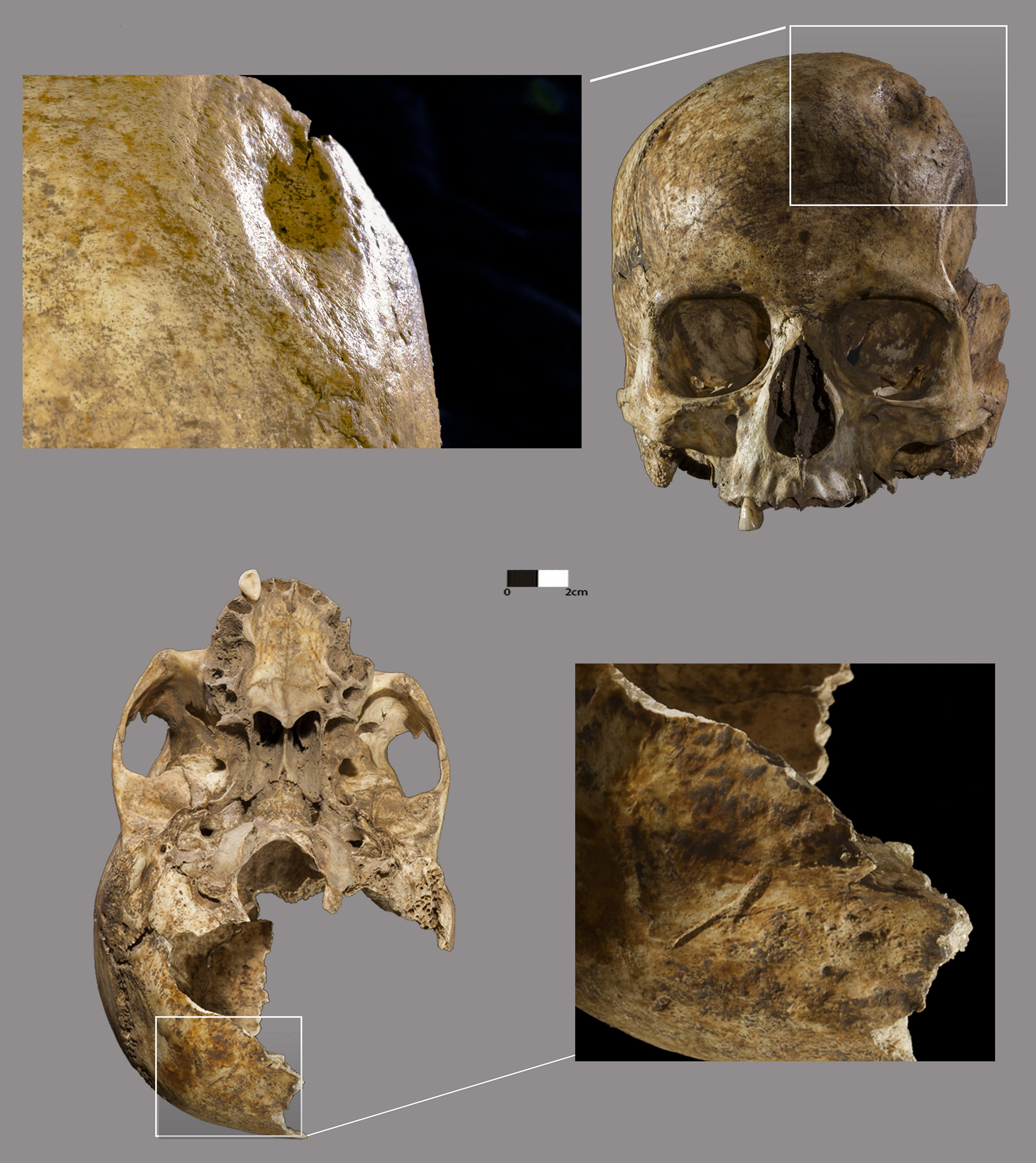

On the upper left side of the possibly-female skull, archaeologists found something strange: a depression or divot, about 0.7 inches (19 millimeters) wide showing signs of later bone growth and healing. There were no cracks radiating from this divot, leading the researchers to conclude that the woman had been the subject of a Stone Age brain surgery called trepanation. Trepanation was the practice of drilling or scraping a hole through the skull into the brain; hundreds of Stone Age skulls have been found with trepanation holes in them. Modern surgeons sometimes remove parts of the skull after a brain injury to relieve pressure from swelling, and it's possible that ancient surgeons had the same reasons for trepanation. But they may also have carried out the surgery because they believed it released evil spirits.

Whatever the reason, the trepanation carried out on the skull was incomplete; the hole did not go completely through the skull. The person likely lived for years after the procedure, the researchers wrote, and the trepanation may have had nothing to do with the woman's strange postmortem fate. Cut marks on the skull indicate that her head had been removed from her body soon after death, while there was still flesh on the bones.

Unknown era

The scene in the cave suggests some sort of ritual, perhaps even a sacrificial ritual, the researchers wrote. The ancient people likely killed the goat for the ritual, but it's not clear whether they also sacrificed the two humans. They may have died naturally, or one may have died naturally and the other may have been a human sacrifice laid to rest with them. Or both may have been deliberately killed.

"This finding opens new lines of research and anthropological scenarios," García-Rivero said in a statement. In these scenarios, human and animal sacrifice may have been part of the rituals of cults dedicated to one's ancestry or part of festivals of commemoration, he said.

Very little is known about the burial practices of the Middle Neolithic, when these skulls were placed in the cave. The new discovery is also an opportunity to compare the practices of people of the Southern Iberian Stone Age with their neighbors farther east, García-Rivero said.

"This discovery is of great importance not only because of its peculiarity, but also because it constitutes a sealed, intact ritual deposit, which is a great opportunity to gain a more detailed insight into the funerary and ritual behaviours of the Neolithic populations of the Iberian Peninsula," he said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.