Sunken settlement discovered beneath a Venice lagoon

The discovery is evidence that much of the Venetian Lagoon was once dry land.

The submerged remains of a Roman road have been found on the seafloor of the Venice lagoon, along with archaeological structures that are thought to be what's left of a dock and settlements.

The remains are thought to date to centuries before Venice was founded in early medieval times, when much of what is now the lagoon was accessible by land.

The new discoveries in the Treporti channel, in the northern part of Venice's outer lagoon, confirm the findings of an archaeological investigation of the area in the 1980s, and suggest that the now-submerged area was mostly dry land, said Fantina Madricardo, a geophysicist with the Institute of Marine Science (ISMAR) in Venice, and lead author of a new study published Thursday (July 22) in the journal Scientific Reports. The area likely had several small permanent settlements and roads that linked them to nearby trading centers, she said.

Related: The 25 most mysterious archaeological finds on Earth

"The Venice lagoon formed from the main sea-level rise after the last glaciation, so it's a long-term process," Madricardo told Live Science. "We know that since Roman times — about 2,000 years — that the sea level there rose [up to] two and a half meters [8 feet]."

The change in sea level means that large areas of the lagoon that are now underwater were once dry land, and archaeological evidence now indicates that the land was crossed by at least one well-built road, she said.

New lagoon

The city of Venice is many centuries old, but there are no records of it in Roman-age writings. Archaeologists believe it began as a collection of villages on islands in the area after the Western Roman Empire collapsed at the end of the fourth century.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Roman artifacts had previously been found in the waterways and on islands in the lagoon, but the extent of human occupation there in Roman times has been unclear; some scientists have suggested the area was well populated, but others have maintained it was mostly devoid of settlements at that time.

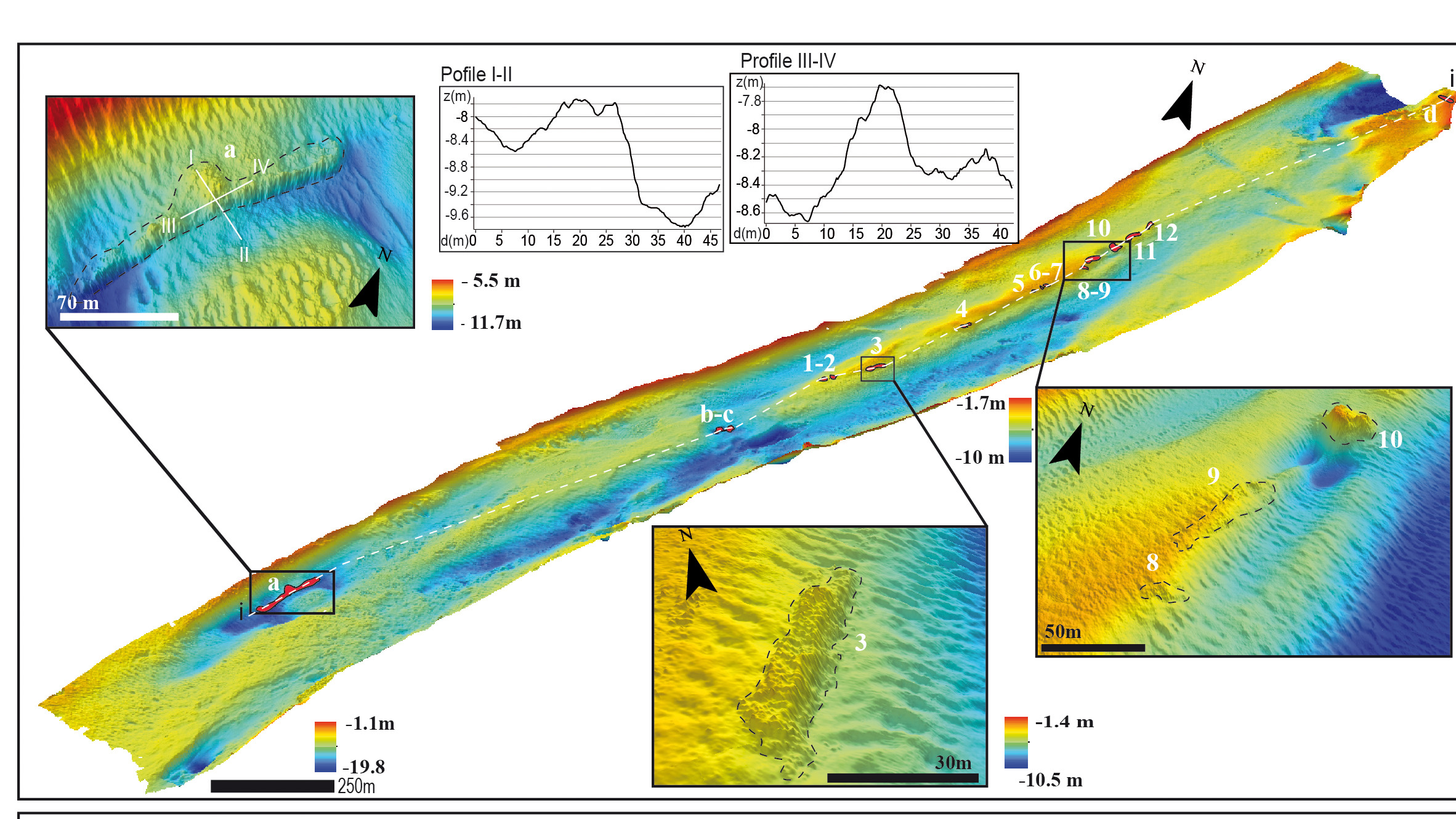

In the latest study, Madricardo and her team used sonar scans and conducted archaeological dives in the Treporti channel in 2020, where they found 12 archaeological structures aligned in a north-easterly direction for a distance of 3,740 feet (1,140 m), Madricardo said.

Related: Real-life 'Atlantis' settlements hidden beneath the waves

The submerged structures are up to 9 feet (2.7 m) tall and up to 170 feet (52 m) long, and are likely the remains of an ancient road-bed built above the surrounding countryside, she said.

Archaeological dives also revealed stones with a smooth upper face and an ovoid underside, similar to Roman basoli — the stones traditionally used to pave the upper surfaces of ancient Roman roads, she said.

The team also found a group of submerged structures hidden beneath the road, at a depth of about 30 feet (9 m). These structures could be the remains of an ancient dock that lay in a water channel beside the road, and the dock once covered an area larger than a basketball court, the researchers said.

Ancient road

Madricardo and her colleagues think the now-submerged road linked the dock and settlements in the area with a network of roads; those roads then would have connected towns in the southern area of what is now the lagoon to the Roman trading center of Altinum in the north.

Related: Sunken cities: Real-life 'Atlantis' settlements hidden beneath the waves

The road likely ran along the top of a sandy ridge, roughly where the outermost islands of the lagoon are today. For much of the road's length, water would have been on both sides — the eastern side being the sea coast and the western side an enclosed waterway, the researchers wrote.

Several small settlements were likely situated at intervals along the road; the archaeologists also found evidence of buildings — roof tiles, bricks and pottery — along the road, Madricardo said.

The investigations have been hampered by massive developments in the area from the 19th and early 20th centuries, including the construction of several large jetties on the Venice Lido, a barrier island just to the south, and the new foreshore of the Punta Sabbioni just to the east, she said.

But they now hope to investigate the submerged ruins further in collaboration with the local authorities for underwater cultural heritage.

So far, the scientists haven't been able to tell exactly when the Roman road was built and for how long it was used before the strip of land it was on was finally covered by the waves.

Although the area has been thoroughly modified in the last 200 years, Madricardo hopes that sediment cores from the floor of the lagoon can be radiocarbon dated, which may reveal more about its age and how long it was in use.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.