Are aliens using a quirk of the sun's gravity to transmit information through an interstellar communication network? For the first time ever, astronomers explored this intriguing possibility and scanned for signals coming from hidden nonhuman probes orbiting the sun.

So far, the method hasn't turned up signs of spacefaring aliens, but it represents a promising new avenue of hunting for aliens as part of the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI).

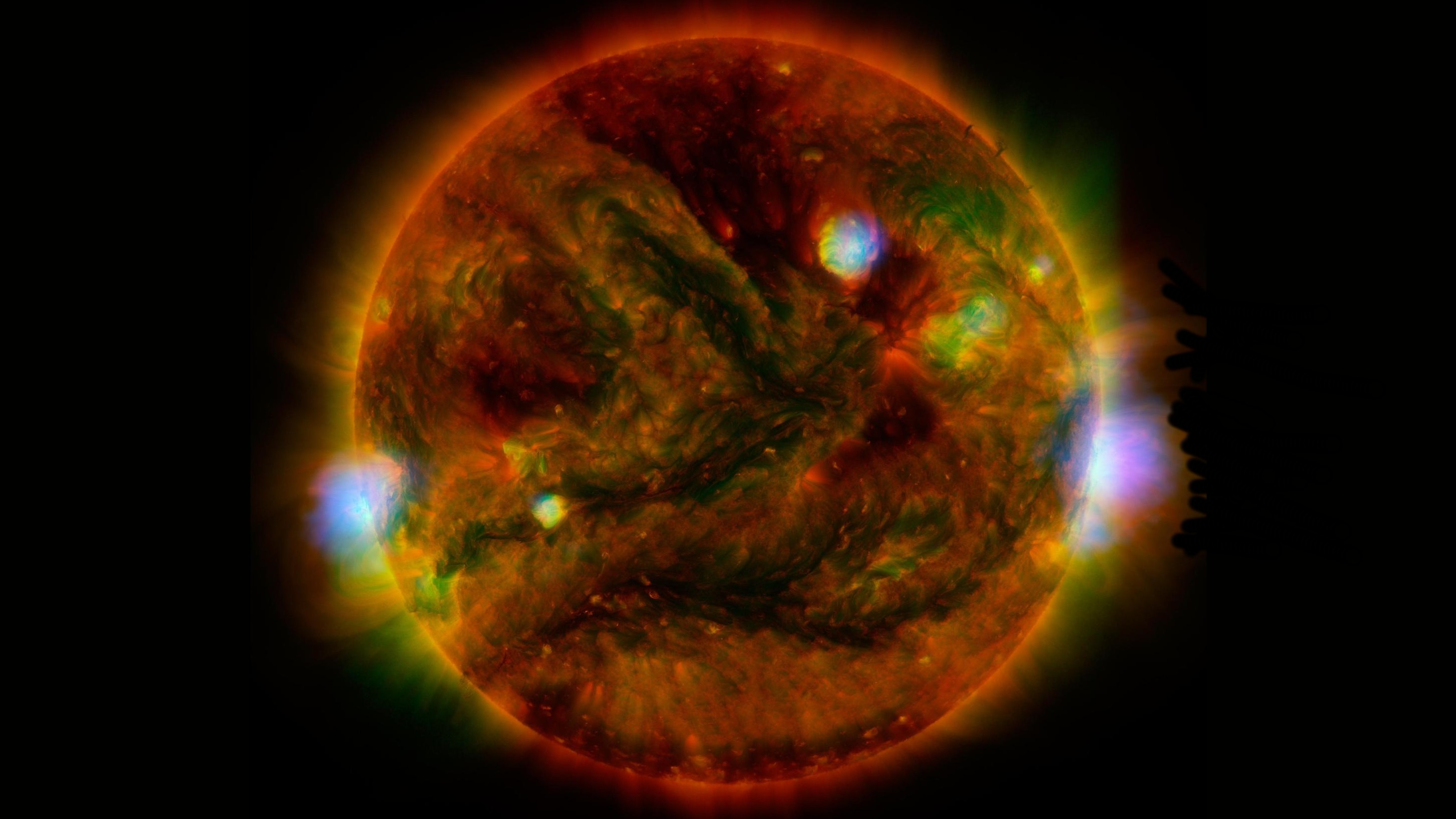

The new search strategy rests on the findings of Albert Einstein, who showed in 1915 that gravity warps the fabric of space-time. This means that massive objects, like stars and galaxies, bend light around them. This effect, known as gravitational lensing, allows scientists to see extremely distant objects whose light has been warped by enormous foreground galaxies and galactic clusters.

"It's a lot like a magnifying glass," Nicholas Tusay, a graduate student at Penn State, told Live Science.

With both gravitational lensing and a magnifying glass, the magnification works best when a person or detector is positioned at a specific place known as the focal point, he said.

The sun's gravitational focal point starts at roughly 550 astronomical units (AU), or 550 times the distance between Earth and the sun, Tusay said. A telescope placed at this spot would have mind-blowing abilities — it could resolve continents and mountains on a planet orbiting another star, he added.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Light goes both ways," Tusay said. "If you can magnify light coming to you, you can also magnify light going out."

This means gravitational lensing also can be used to efficiently send signals across interstellar distances, so scientists have speculated about tech-savvy aliens placing probes at the focal points of stars, effectively turning them into a gigantic point-to-point communication network.

To test this idea, Tusay and his colleagues used the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia to conduct six five-minute scans for radio signals coming from the sun's gravitational focal point. And what did they find?

"Nothing," he said. "To state it accurately: In the frequencies we observed, during the time we observed, we found no compelling signals that were extraterrestrial in origin."

The results were published last summer in The Astronomical Journal and were presented last week by Tusay at the 241st meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Seattle.

While the findings aren't yet evidence of ET, Tusay said it's possible that alien probes placed at the sun's gravitational focal point turn on only from time to time. And other stars have properties that make them better nodes in a gigantic space internet, so these could be additional search targets, he added. He sees the method as more of a proof-of-concept that might turn up something interesting if conducted for longer and with more resources.

"We're always talking about new ways to search in the field of SETI," Julia DeMarines, an astrobiologist at the University of California, Berkeley who was not involved in the work, told Live Science. "This is the first time I've seen a dedicated search to this specific possibility of intercepting messages."

When nothing is seen in a SETI search, it could mean several things, she added, including that nobody is out there communicating, or merely that nobody is communicating in these ways. Any new search method is always welcome, DeMarines said. "If you don't look," she added, "then you'll never know."

Adam Mann is a freelance journalist with over a decade of experience, specializing in astronomy and physics stories. He has a bachelor's degree in astrophysics from UC Berkeley. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, New York Times, National Geographic, Wall Street Journal, Wired, Nature, Science, and many other places. He lives in Oakland, California, where he enjoys riding his bike.