The sun may be coming out of its slumber at long last.

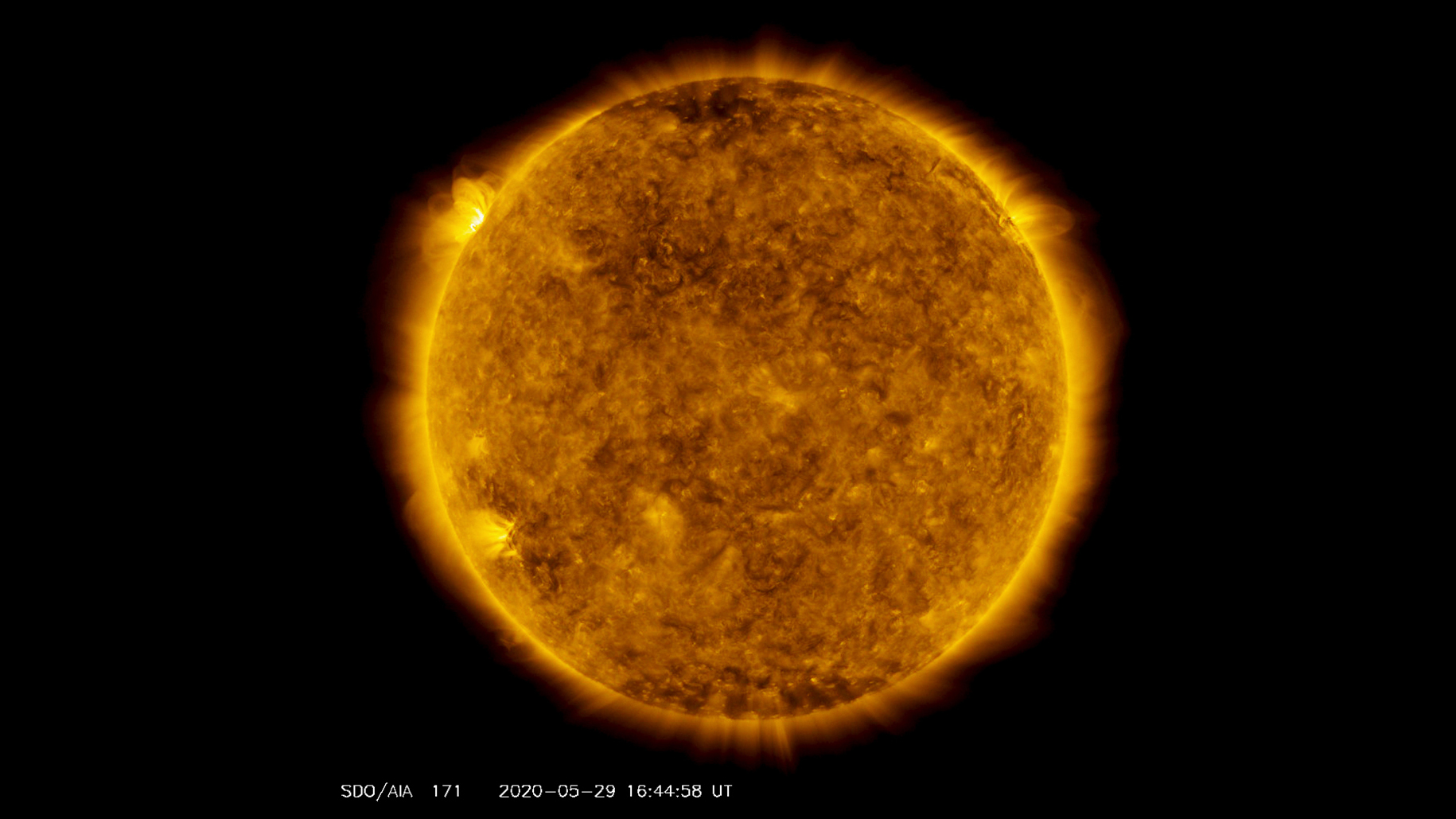

On Friday morning (May 29), our star fired off its strongest flare since October 2017, an eruption spotted by NASA's sun-watching Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO).

Solar flares are bursts of radiation that originate from sunspots, temporary dark and relatively cool patches on the solar surface that boast very strong magnetic fields. Scientists classify strong flares into three categories: C, M and X. Each class is 10 times more powerful than the one beneath it; M flares are 10 times stronger than C flares, but 10 times weaker than X-class events.

Related: The sun's wrath: Worst solar storms in history

Today's flare was an M-class eruption, so it was no monster. (And it wasn't aimed at Earth, so there's no chance of supercharged auroras from a potential associated coronal mass ejection of solar plasma.) But the outburst could still be a sign that the sun is ramping up to a more active phase of its 11-year activity cycle, NASA officials said. If that's the case, the most recent such cycle, known as Solar Cycle 24, may already have come to an end.

Scientists peg the start of new cycles at "solar minimum," the time when the sun sports the fewest sunspots and the least activity.

"However, it takes at least six months of solar observations and sunspot-counting after a minimum to know when it's occurred," NASA officials wrote today in an update announcing SDO's flare detection.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Related: The sun has 2 kinds of spots right now amid solar cycle change

"Because that minimum is defined by the lowest number of sunspots in a cycle, scientists need to see the numbers consistently rising before they can determine when exactly they were at the bottom," the officials added. "That means solar minimum is an instance only recognizable in hindsight: It could take six to 12 months after the fact to confirm when minimum has actually passed."

So, stay tuned! More observations should tell us if we're already in Solar Cycle 25.

- There are two kinds of sunspots on the sun right now amid solar cycle change

- 10 brilliant discoveries NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory made in its first decade

- Our sun will never look the same again thanks to two solar probes and one giant telescope

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.