'Reaper of death,' newfound cousin of T. rex, discovered in Canada

The "reaper of death" is the first newfound tyrannosaur species to be named in Canada in 50 years.

The fossils of a newly discovered Tyrannosaurus rex cousin — a vicious, meat-eating dinosaur with serrated teeth and a monstrous face that scientists are calling the "reaper of death," has been discovered in Alberta, Canada.

At 79.5 million years old, Thanatotheristes degrootorum is the oldest known named tyrannosaur on record from northern North America, a region that includes Canada and the northern part of the western United States, said researchers of a new study on the discovery. It's also the first previously unknown tyrannosaur species to be discovered in Canada in 50 years.

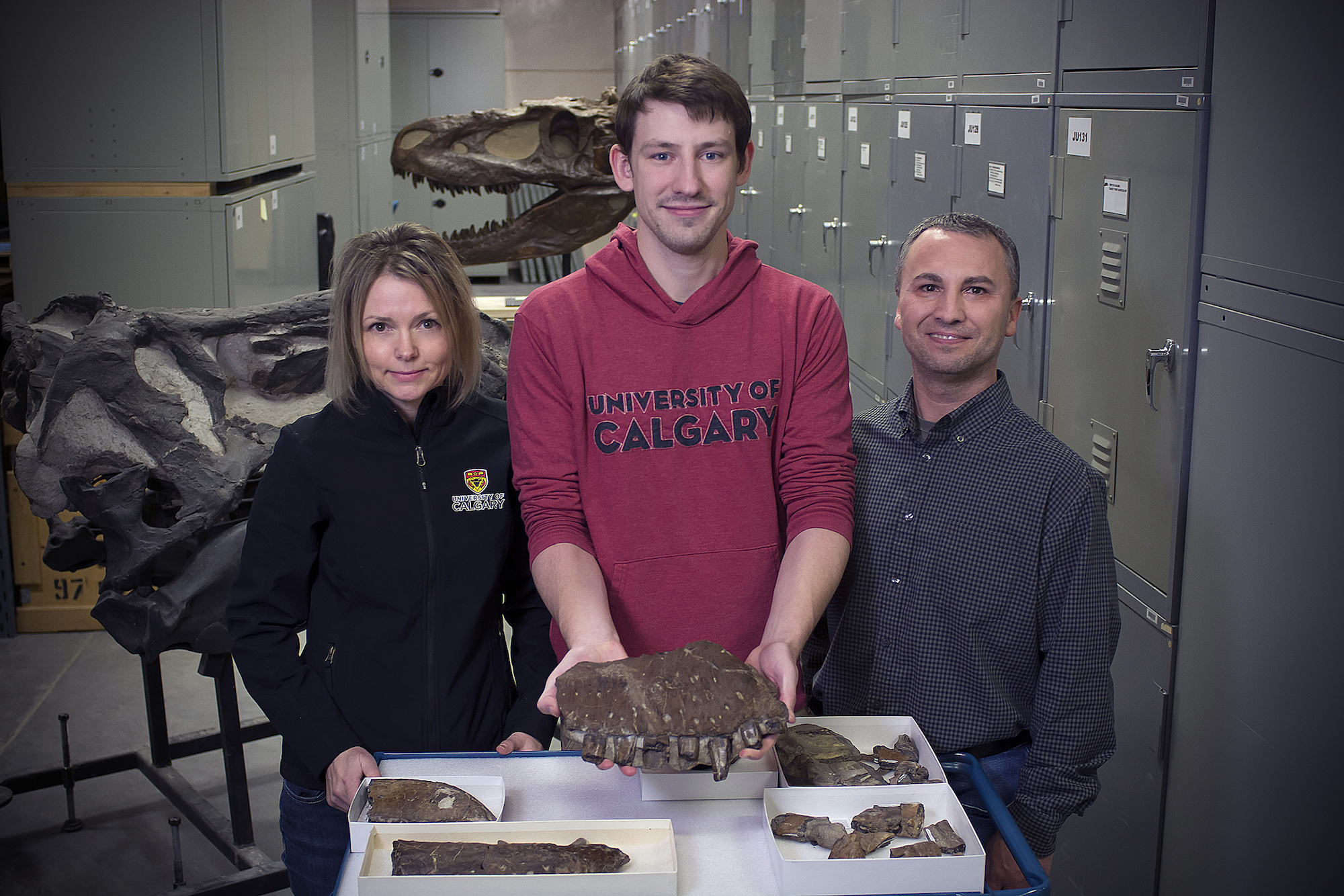

"It definitely would have been quite an imposing animal, roughly 8 feet (2.4 meters) [tall] at the hips," study lead researcher Jared Voris, a doctoral student of paleontology at the University of Calgary in Alberta, told Live Science.

Related: Photos: Newfound Tyrannosaur had nearly 3-inch-long teeth

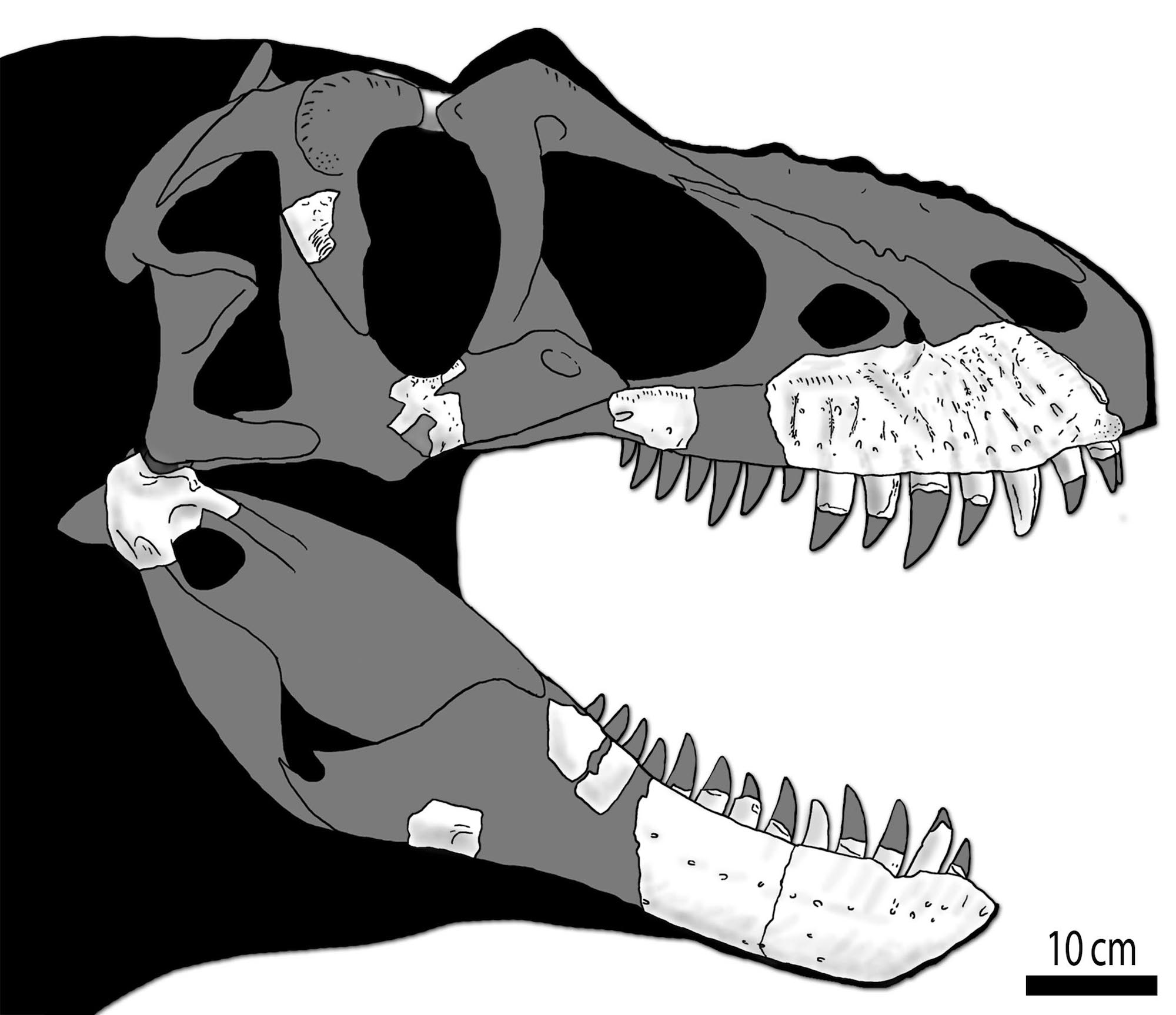

T. degrootorum lived during the Cretaceous period, the last period of the dinosaur age, which lasted from about 145 million to 65 million years ago. The imposing beast had a mouthful of steak-knife-like teeth that were more than 2.7 inches (7 centimeters) long. From snout to tail, the dinosaur measured about 26 feet (8 meters) long, or about the length of four king-size mattresses lined up end to end.

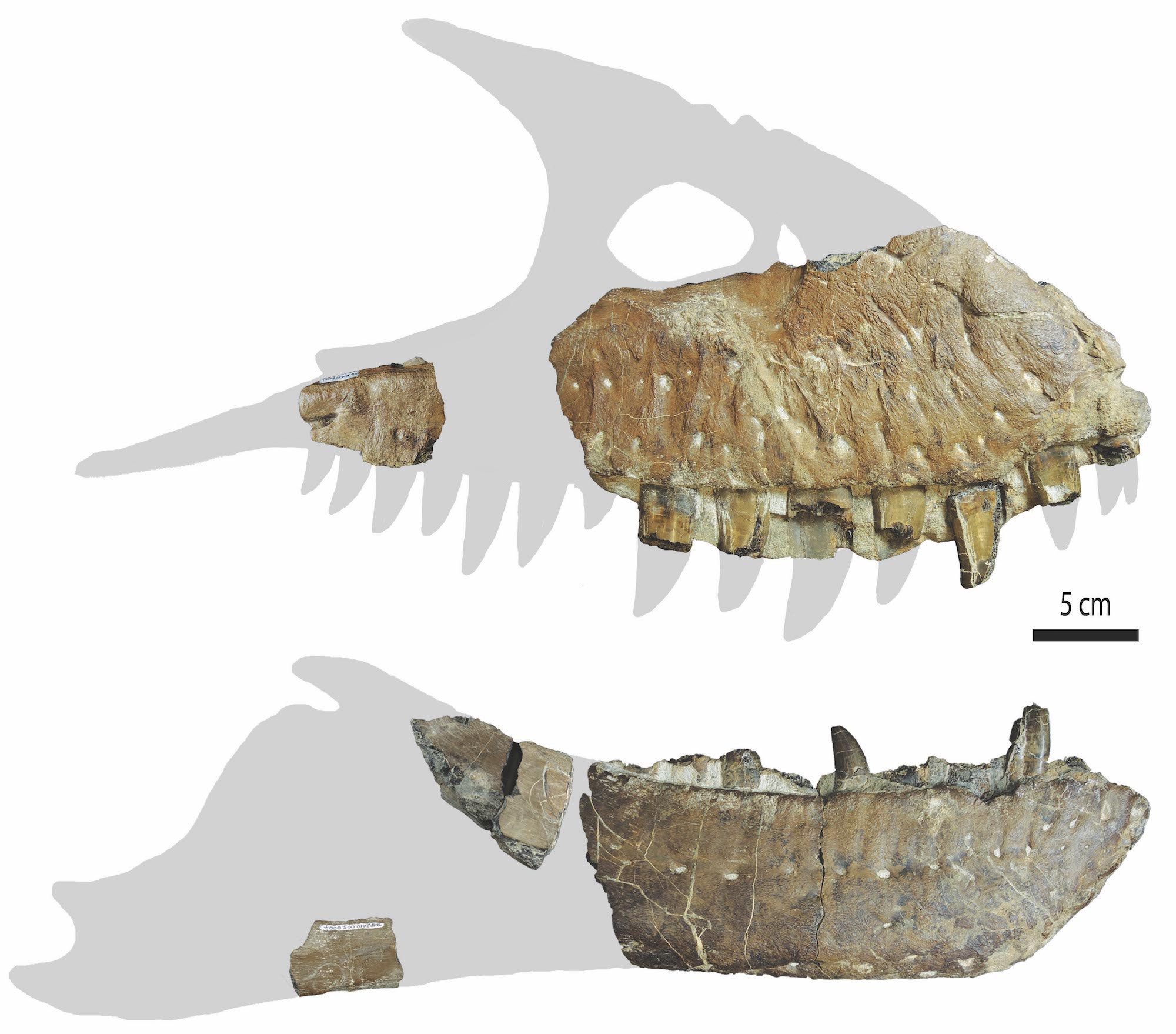

The researchers have only two partial skulls and jaws of the newfound tyrannosaur (so they couldn't estimate its mass, as the hind limbs are needed for that calculation), but the unearthed fossils were enough to define the creature as a newfound species, they said.

Like other tyrannosaurs, the "reaper of death" ("Thanatos" is the Greek god of death and "theristes" is Greek for "reaper," which is how the team derived Thanatotheristes), had strange bumps on its skull that gave it a monstrous appearance. But it also had a one-of-a-kind feature: a distinct set of vertical ridges that ran from its eyes along its upper snout.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"These ridges are not like anything we've ever seen before in other tyrannosaur species," Voris said. "Exactly what the ridges do, we're not quite sure."

Dinosaur on the shore

Parts of the dinosaur's skull and jaws were discovered by the Canadian couple John and Sandra De Groot of Hays, Alberta, who spotted the dinosaur's remains in 2010 on the shore of the Bow River, in southern Alberta. Another skull was found nearby, also in Alberta's Foremost Formation, a rock unit that contains the remains of surprisingly few dinosaur species.

The only other dinosaurs found in this rock formation were plant eaters: the horned dinosaur and Triceratops relative Xenoceratops foremostensis and the pachycephalosaur (a type of dinosaur with a helmet-like skull) Colepiocephale lambei, study co-researcher Darla Zelenitsky, an assistant professor of paleontology at the University of Calgary, told Live Science.

Given that these herbivores are from the same rock layer as T. degrootorum, it's a good guess that they were the daily special on the carnivore's menu, Zelenitsky said.

The De Groot family told the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Alberta about the discovery, but it wasn't until Voris was going through the museum's collections that he realized it was a newfound species. After studying the nearly 3-foot-long (80 cm) skulls, Voris and his colleagues found that T. degrootorum was similar to other tyrannosaurs in southern Alberta and Montana, including Daspletosaurus, because it had a long and deep snout.

Related: Gory guts: Photos of a T. rex autopsy

"These [features] differ from tyrannosaur groups in other regions: the more lightly built relatives, like Albertosaurus, that tended to live slightly farther north in south-central Alberta, and more primitive forms with shorter, bulldog-like faces of the southern USA, [including] New Mexico and Utah," Zelenitsky said.

It's unclear why these tyrannosaurs had such different body types and head shapes, but it could be due to differences in diet — that is, the type of prey they ate and their strategy for hunting them, Zelenitsky said.

The new discovery shows that Daspletosaurus-like tyrannosaurs were diversifying in the northern part of western North America about 80 million years ago, said Steve Brusatte, a paleontologist at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, who wasn't involved in the study. But these long- and deep-snouted tyrannosaurs appeared to stay in their neck of the woods, he said.

"This seems to be a bigger theme: There were different subgroups of tyrannosaurs characteristic of certain times and places, and they did not all mix together," Brusatte told Live Science.

Moreover, T. degrootorum wasn't as huge as T. rex, which lived about 12 million years later, but its discovery shows that tyrannosaurs "weren't all colossal hypercarnivores like T. rex, but there were many subgroups that had their own domains and their own unique body types and probably hunting styles during the very latest Cretaceous period," Brusatte said.

The study was published online Jan. 23 in the journal Cretaceous Research.

- Photos: The first dino fossil found in Washington

- Dinosaur guts: Photos of a paleo-predator

- Photos: Newfound dinosaur had tiny arms, just like T. rex

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.