Cryptic lost Canaanite language decoded on 'Rosetta Stone'-like tablets

Two ancient clay tablets from Iraq contain details of a "lost" Canaanite language.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

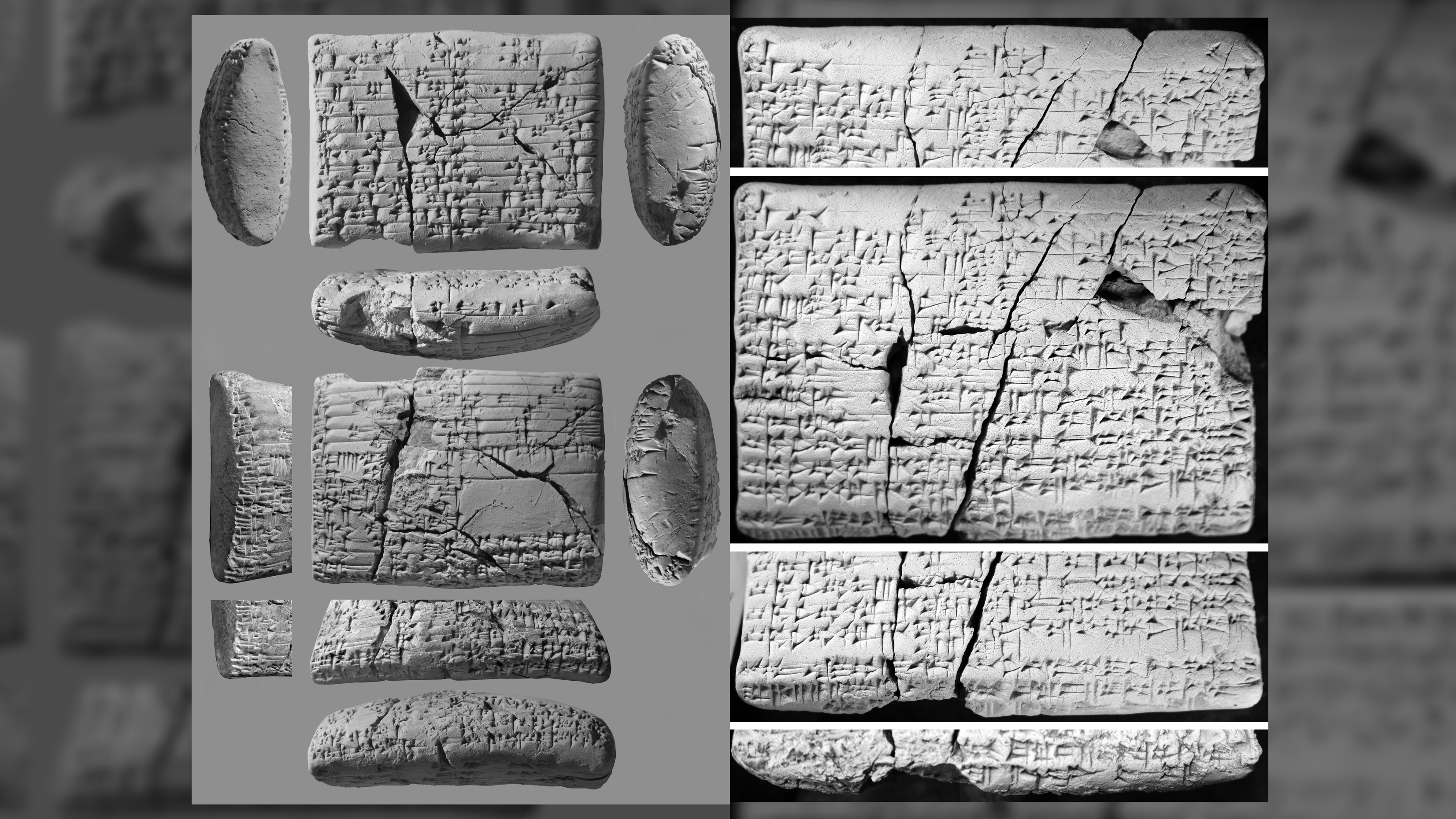

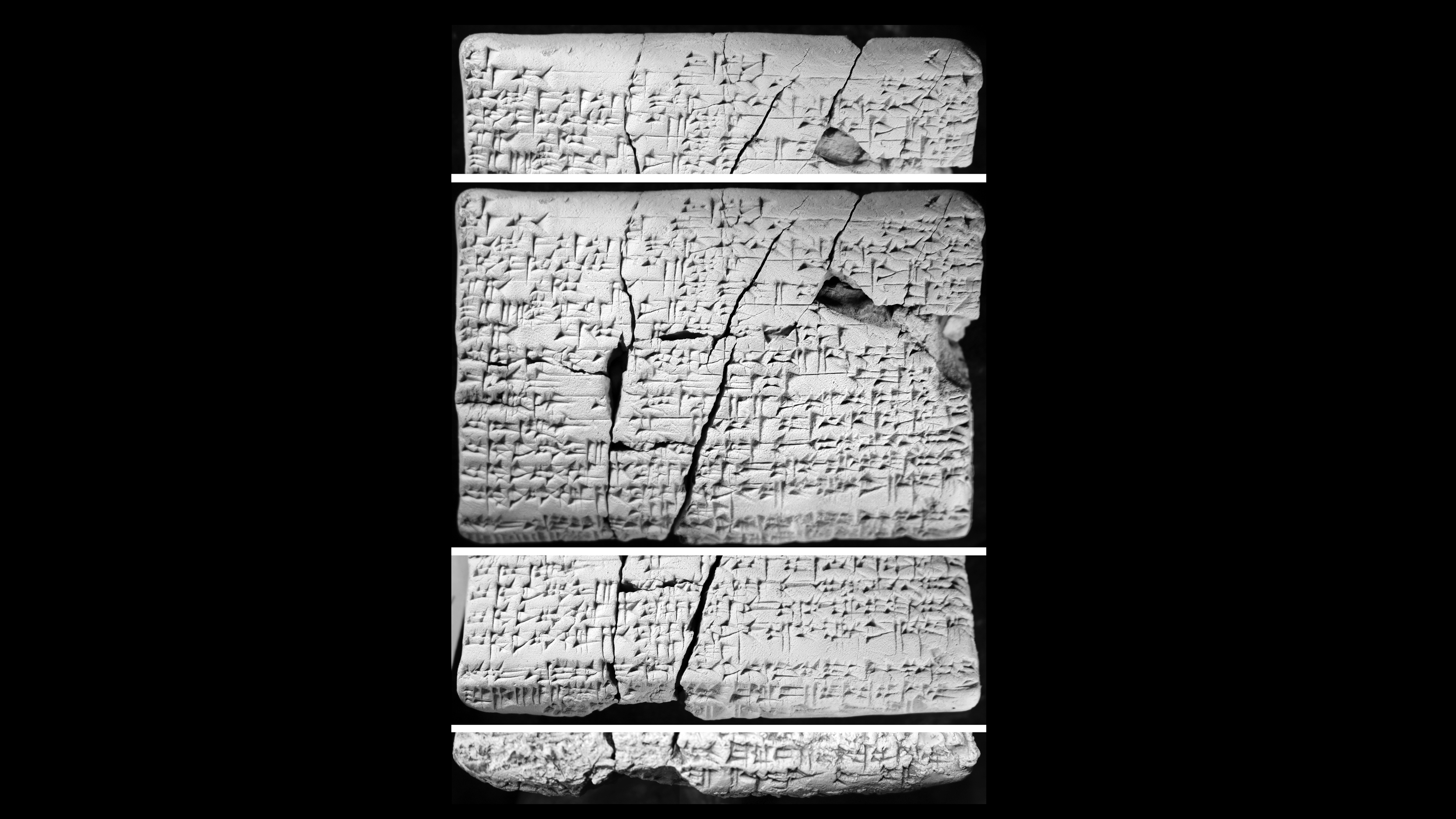

Two ancient clay tablets discovered in Iraq and covered from top to bottom in cuneiform writing contain details of a "lost" Canaanite language that has remarkable similarities with ancient Hebrew.

The tablets, thought to be nearly 4,000 years old, record phrases in the almost unknown language of the Amorite people, who were originally from Canaan — the area that's roughly now Syria, Israel and Jordan — but who later founded a kingdom in Mesopotamia. These phrases are placed alongside translations in the Akkadian language, which can be read by modern scholars.

In effect, the tablets are similar to the famous Rosetta Stone, which had an inscription in one known language (ancient Greek) in parallel with two unknown written ancient Egyptian scripts (hieroglyphics and demotic.) In this case, the known Akkadian phrases are helping researchers read written Amorite.

"Our knowledge of Amorite was so pitiful that some experts doubted whether there was such a language at all," researchers Manfred Krebernik and Andrew R. George told Live Science in an email. But "the tablets settle that question by showing the language to be coherently and predictably articulated, and fully distinct from Akkadian."

Krebernik, a professor and chair of ancient Near Eastern studies at the University of Jena in Germany, and George, an emeritus professor of Babylonian literature at the University of London's School of Oriental and African Studies, published their research describing the tablets in the latest issue of the French journal Revue d'assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale (Journal of Assyriology and Oriental Archaeology).

Related: Why does the Rosetta Stone have 3 kinds of writing?

Lost language

The two Amorite-Akkadian tablets were discovered in Iraq about 30 years ago, possibly during the Iran-Iraq War, from 1980 to 1988; eventually they were included in a collection in the United States. But nothing else is known about them, and it's not known if they were taken legally from Iraq.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Krebernik and George started studying the tablets in 2016 after other scholars pointed them out.

By analyzing the grammar and vocabulary of the mystery language, they determined that it belonged to the West Semitic family of languages, which also includes Hebrew (now spoken in Israel) and Aramaic, which was once widespread throughout the region but is now spoken only in a few scattered communities in the Middle East.

After seeing the similarities between the mystery language and what little is known of Amorite, Krebernik and George determined that they were the same, and that the tablets were describing Amorite phrases in the Old Baylonian dialect of Akkadian.

The account of the Amorite language given in the tablets is surprisingly comprehensive. "The two tablets increase our knowledge of Amorite substantially, since they contain not only new words but also complete sentences, and so exhibit much new vocabulary and grammar," the researchers said. The writing on the tablets may have been done by an Akkadian-speaking Babylonian scribe or scribal apprentice, as an "impromptu exercise born of intellectual curiosity," the authors added.

Yoram Cohen, a professor of Assyriology at Tel Aviv University in Israel who wasn't involved in the research, told Live Science that the tablets seem to be a sort of "tourist guidebook" for ancient Akkadian speakers who needed to learn Amorite.

One notable passage is a list of Amorite gods that compares them with corresponding Mesopotamian gods, and another passage details welcoming phrases.

"There are phrases about setting up a common meal, about doing a sacrifice, about blessing a king," Cohen said. "There is even what may be a love song. … It really encompasses the entire sphere of life."

Strong similarities

Many of the Amorite phrases given in the tablets are similar to phrases in Hebrew, such as "pour us wine" — "ia -a -a -nam si -qí-ni -a -ti" in Amorite and "hasqenu yain" in Hebrew — although the earliest-known Hebrew writing is from about 1,000 years later, Cohen said.

"It stretches the time when these [West Semitic] languages are documented. … Linguists can now examine what changes these languages have undergone through the centuries," he said.

Akkadian was originally the language of the early Mesopotamian city of Akkad (also known as Agade) from the third millennium B.C., but it became widespread throughout the region in later centuries and cultures, including the Babylonian civilization from about the 19th to the sixth centuries B.C.

Many of the clay tablets covered in the ancient cuneiform script — one of the earliest forms of writing, in which wedge-shaped impressions were made in wet clay with a stylus — were written in Akkadian, and a thorough understanding of the language was a key part of education in Mesopotamia for more than a thousand years.

Editor's note: Updated at 10:06 a.m. EST on Feb. 3 to fix the pronunciation of "pour us wine" in Hebrew and to note that Yoram Cohen is a full, not an associate professor.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus