Adorable tardigrades fight UV rays with glowing shield

Though small, tardigrades are known for their toughness.

Scientists have discovered yet another reason to be impressed with tardigrades; some of these microscopic, nearly indestructible creatures wear a glowing "shield" that protects them from ultraviolet radiation.

Tubby tardigrades — also called moss piglets or water bears — are known for their toughness, able to withstand extreme heat, cold and pressure, as well as the vacuum of space. They can also survive exposure to levels of radiation that would kill many other life-forms.

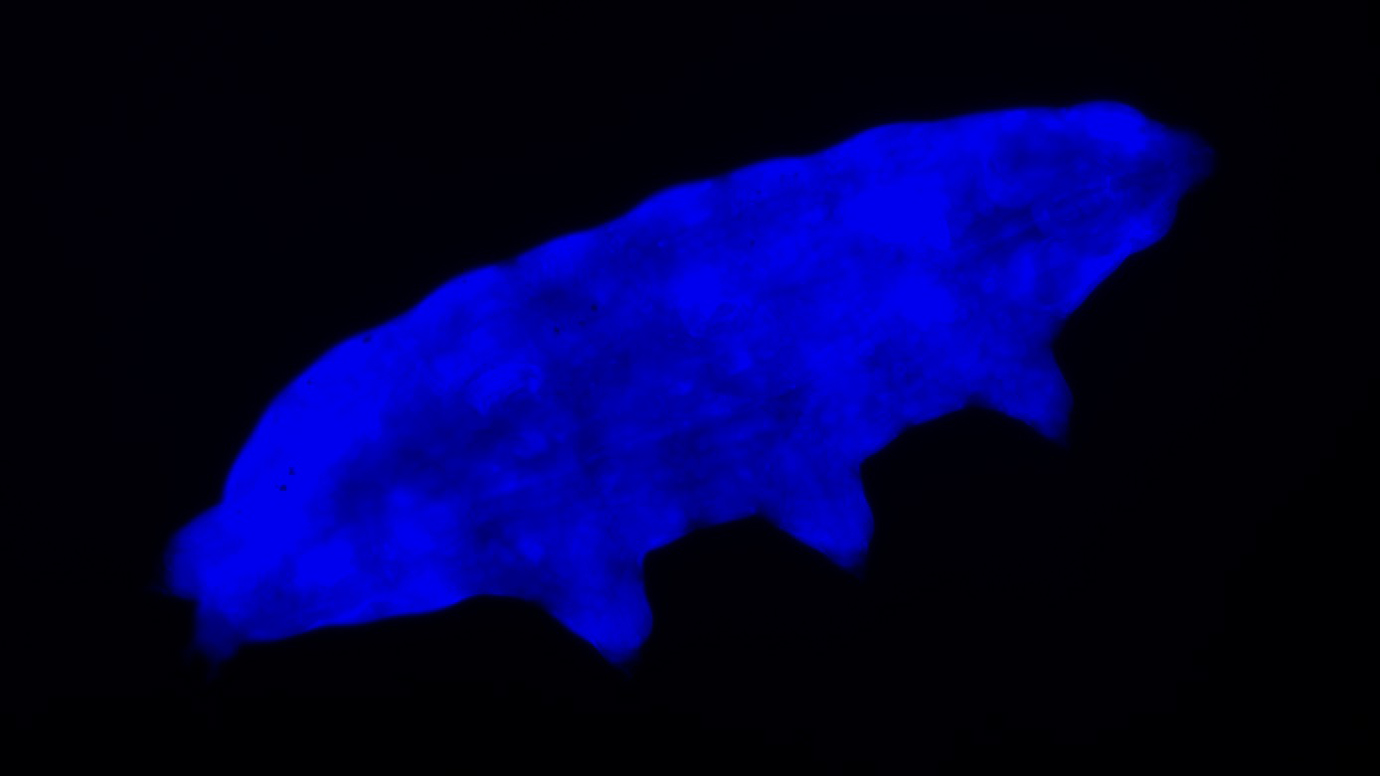

Now, scientists have uncovered new clues about tardigrades' radiation resistance. Experiments with tardigrades in the Paramacrobiotus genus revealed that fluorescence protects them like a layer of sunscreen, transforming damaging UV rays into harmless blue light, according to a new study.

Related: 8 reasons why we love tardigrades

Biofluorescence bathes diverse creatures in an eerie radiance. It differs from bioluminescence, which sparks light through a chemical reaction between compounds in the animal's body; think of the bioluminescent glimmer produced by fireflies, for example.

In fluorescent animals, their glow — usually red or green — isn't the result of a chemical reaction. Rather, these animals fluoresce when molecules inside their cells absorb light particles, or photons, from invisible UV rays and emit lower-energy light in a longer wavelength. There are sea turtles with fluorescent shells and heads, and tiny orange frogs and chameleons with fluorescent bones. Jellyfish glow with fluorescent light, as do scorpions, parrots, nematodes and yes — tardigrades, said lead study author Sandeep M. Eswarappa, an assistant professor in the Department of Biochemistry at the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore, India.

Yet little is known about how most fluorescent species use their glow. For the new study, the authors questioned if fluorescence in tardigrades might be linked to the water bears' radiation tolerance.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Both phenomena were connected"

The scientists tested Paramacrobiotus tardigrades' UV resistance by exposing them to 15 minutes of radiation at levels high enough to kill most microorganisms. All of the Paramacrobiotus tardigrades were still alive 30 days later, while Hypsibius exemplaris tardigrades that were UV-sensitive all died within 24 hours of radiation exposure, according to the study.

"There was no difference in the survival of these two tardigrade species when they were not treated with UV radiation," Eswarappa told Live Science in an email.

Paramacrobiotus tardigrades also glowed brightly when exposed to UV light. However, when the researchers extracted fluorescent components from Paramacrobiotus tardigrades and applied them to both H. exemplaris and the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans — which also is non-fluorescent and sensitive to UV — the two species "showed partial tolerance to UV radiation," the researchers reported.

"It was natural to think that both phenomena were connected," Eswarappa said.

Prior studies hint that biofluorescence may offer UV protection in certain corals, and researchers hunting for extraterrestrial life suggest that biofluorescence could help organisms evolve and survive on distant worlds orbiting red dwarf stars — which have a higher UV output than our sun — potentially populating planets with many varieties of luminous creatures, Live Science previously reported.

For glowing Earthbound tardigrades, fluorescence could increase their chances of surviving in habitats where the water bears are often exposed to the sun, Eswarappa said.

"UV resistance provides these tardigrades with an ability to thrive in environments with a high UV index. For example, in tropical regions," he said.

The findings were published online Oct. 13 in the journal Biology Letters.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.