New AI is better at weather prediction than supercomputers — and it consumes 1000s of times less energy

The Aardvark Weather machine learning algorithm is much faster than traditional systems and can work on a desktop computer.

A new artificial intelligence (AI)-driven weather prediction system could transform forecasting, researchers predict

The system, dubbed Aardvark Weather, generates forecasts tens of times faster than traditional forecasting systems using a fraction of the computing power, researchers reported Thursday (March 20) in the journal Nature.

"The weather forecasting systems we all rely on have been developed over decades, but in just 18 months, we've been able to build something that's competitive with the best of these systems, using just a tenth of the data on a desktop computer," Richard Turner, an engineer at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, said in a statement.

Current weather forecasts are generated by inputting data into complex physics models, a multi-stage process that requires several hours on a dedicated supercomputer.

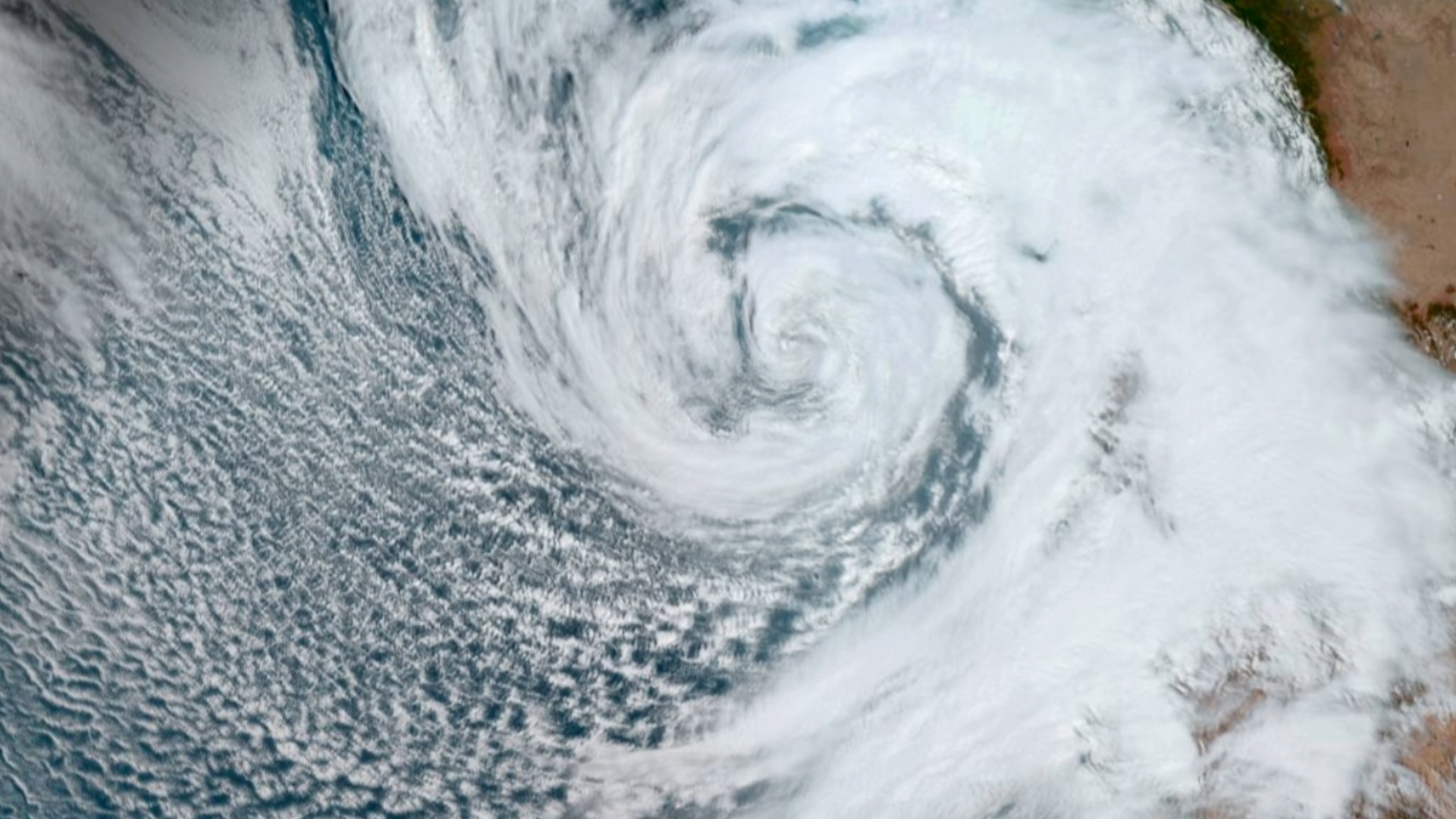

Aardvark Weather circumvents this demanding process: the machine learning model uses raw data from satellites, weather stations, ships and weather balloons to make its predictions without relying on atmospheric models. Satellite data are particularly important for the model's predictions, the team noted.

Related: Google builds an AI model that can predict future weather catastrophes

This new approach could offer major advantages in terms of cost, speed and accuracy of weather forecasts, the researchers claimed. Instead of requiring a supercomputer and a dedicated team, Aardvark Weather can generate a forecast on a desktop computer in just a few minutes.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Replacing the weather prediction pipeline with AI

The team compared Aardvark's performance to existing forecasting systems that generate global predictions. Using just 8% of the observational data that traditional forecasting systems need, Aardvark outperformed the U.S. national Global Forecast System (GFS)system and was comparable to forecasts made by the United States Weather Service.

However, Aardvark's spatial resolution is somewhat lower than those of current forecasting systems, which could make its initial predictions less relevant for hyper-local weather forecasting. Aardvark Weather operates at 1.5-degree resolution, meaning each box in its grid covers 1.5 degrees of latitude and 1.5 degrees of longitude. For comparison, the GFS uses a 0.25-degree grid.

However, the researchers also said that because the AI learns from the data it is fed, it could be tailored to predict weather in specific arenas — such as temperatures for African agriculture or wind speeds for renewable energy in Europe. Aardvark can incorporate higher-resolution regional data, where they exist, to refine local forecasts.

"These results are just the beginning of what Aardvark can achieve," study coauthor Anna Allen, of the University of Cambridge, said in the statement. "This end-to-end learning approach can be easily applied to other weather forecasting problems, for example hurricanes, wildfires, and tornadoes. Beyond weather, its applications extend to broader Earth system forecasting, including air quality, ocean dynamics, and sea ice prediction."

Aardvark could also support forecasting centers in areas of the world that lack the resources to refine global forecasts into high-resolution regional predictions, the researchers said.

"Aardvark's breakthrough is not just about speed, it's about access," Scott Hosking, an AI researcher at The Alan Turing Institute in the U.K., said in the statement. "By shifting weather prediction from supercomputers to desktop computers, we can democratize forecasting, making these powerful technologies available to developing nations and data-sparse regions around the world."

Skyler Ware is a freelance science journalist covering chemistry, biology, paleontology and Earth science. She was a 2023 AAAS Mass Media Science and Engineering Fellow at Science News. Her work has also appeared in Science News Explores, ZME Science and Chembites, among others. Skyler has a Ph.D. in chemistry from Caltech.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.