Rapid progress in artificial intelligence (AI) is prompting people to question what the fundamental limits of the technology are. Increasingly, a topic once consigned to science fiction — the notion of a superintelligent AI — is now being considered seriously by scientists and experts alike.

The idea that machines might one day match or even surpass human intelligence has a long history. But the pace of progress in AI over recent decades has given renewed urgency to the topic, particularly since the release of powerful large language models (LLMs) by companies like OpenAI, Google and Anthropic, among others.

Experts have wildly differing views on how feasible this idea of "artificial super intelligence" (ASI) is and when it might appear, but some suggest that such hyper-capable machines are just around the corner. What’s certain is that if, and when, ASI does emerge, it will have enormous implications for humanity’s future.

"I believe we would enter a new era of automated scientific discoveries, vastly accelerated economic growth, longevity, and novel entertainment experiences," Tim Rocktäschel, professor of AI at University College London and a principal scientist at Google DeepMind told Live Science, providing a personal opinion rather than Google DeepMind's official position. However, he also cautioned: "As with any significant technology in history, there is potential risk."

What is artificial superintelligence (ASI)?

Traditionally, AI research has focused on replicating specific capabilities that intelligent beings exhibit. These include things like the ability to visually analyze a scene, parse language or navigate an environment. In some of these narrow domains AI has already achieved superhuman performance, Rocktäschel said, most notably in games like go and chess.

The stretch goal for the field, however, has always been to replicate the more general form of intelligence seen in animals and humans that combines many such capabilities. This concept has gone by several names over the years, including “strong AI” or “universal AI”, but today it is most commonly called artificial general intelligence (AGI).

"For a long time, AGI has been a far away north star for AI research," Rocktäschel said. "However, with the advent of foundation models [another term for LLMs] we now have AI that can pass a broad range of university entrance exams and participate in international math and coding competitions."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Related: GPT-4.5 is the first AI model to pass an authentic Turing test, scientists say

This is leading people to take the possibility of AGI more seriously, said Rocktäschel. And crucially, once we create AI that matches humans on a wide range of tasks, it may not be long before it achieves superhuman capabilities across the board. That's the idea, anyway. "Once AI reaches human-level capabilities, we will be able to use it to improve itself in a self-referential way," Rocktäschel said. "I personally believe that if we can reach AGI, we will reach ASI shortly, maybe a few years after that."

Once that milestone has been reached, we could see what British mathematician Irving John Good dubbed an "intelligence explosion" in 1965. He argued that once machines become smart enough to improve themselves, they would rapidly achieve levels of intelligence far beyond any human. He described the first ultra-intelligent machine as "the last invention that man need ever make."

Renowned futurist Ray Kurzweil has argued this would lead to a "technological singularity" that would suddenly and irreversibly transform human civilization. The term draws parallels with the singularity at the heart of a black hole, where our understanding of physics breaks down. In the same way, the advent of ASI would lead to rapid and unpredictable technological growth that would be beyond our comprehension.

Exactly when such a transition might happen is debatable. In 2005, Kurzweil predicted AGI would appear by 2029, with the singularity following in 2045, a prediction he’s stuck to ever since. Other AI experts offer wildly varying predictions — from within this decade to never. But a recent survey of 2,778 AI researchers found that, on aggregate, they believe there is a 50% chance ASI could appear by 2047. A broader analysis concurred that most scientists agree AGI might arrive by 2040.

What would ASI mean for humanity?

The implications of a technology like ASI would be enormous, prompting scientists and philosophers to dedicate considerable time to mapping out the promise and potential pitfalls for humanity.

On the positive side, a machine with almost unlimited capacity for intelligence could solve some of the world’s most pressing challenges, said Daniel Hulme, CEO of the AI companies Satalia and Conscium. In particular, super intelligent machines could "remove the friction from the creation and dissemination of food, education, healthcare, energy, transport, so much that we can bring the cost of those goods down to zero," he told Live Science.

The hope is that this would free people from having to work to survive and could instead spend time doing things they’re passionate about, Hulme explained. But unless systems are put in place to support those whose jobs are made redundant by AI, the outcome could be bleaker. "If that happens very quickly, our economies might not be able to rebalance, and it could lead to social unrest,” he said.

This also assumes we could control and direct an entity much more intelligent than us — something many experts have suggested is unlikely. "I don't really subscribe to this idea that it will be watching over us and caring for us and making sure that we're happy," said Hulme. "I just can't imagine it would care."

The possibility of a superintelligence we have no control over has prompted fears that AI could present an existential risk to our species. This has become a popular trope in science fiction, with movies like "Terminator" or "The Matrix" portraying malevolent machines hell-bent on humanity's destruction.

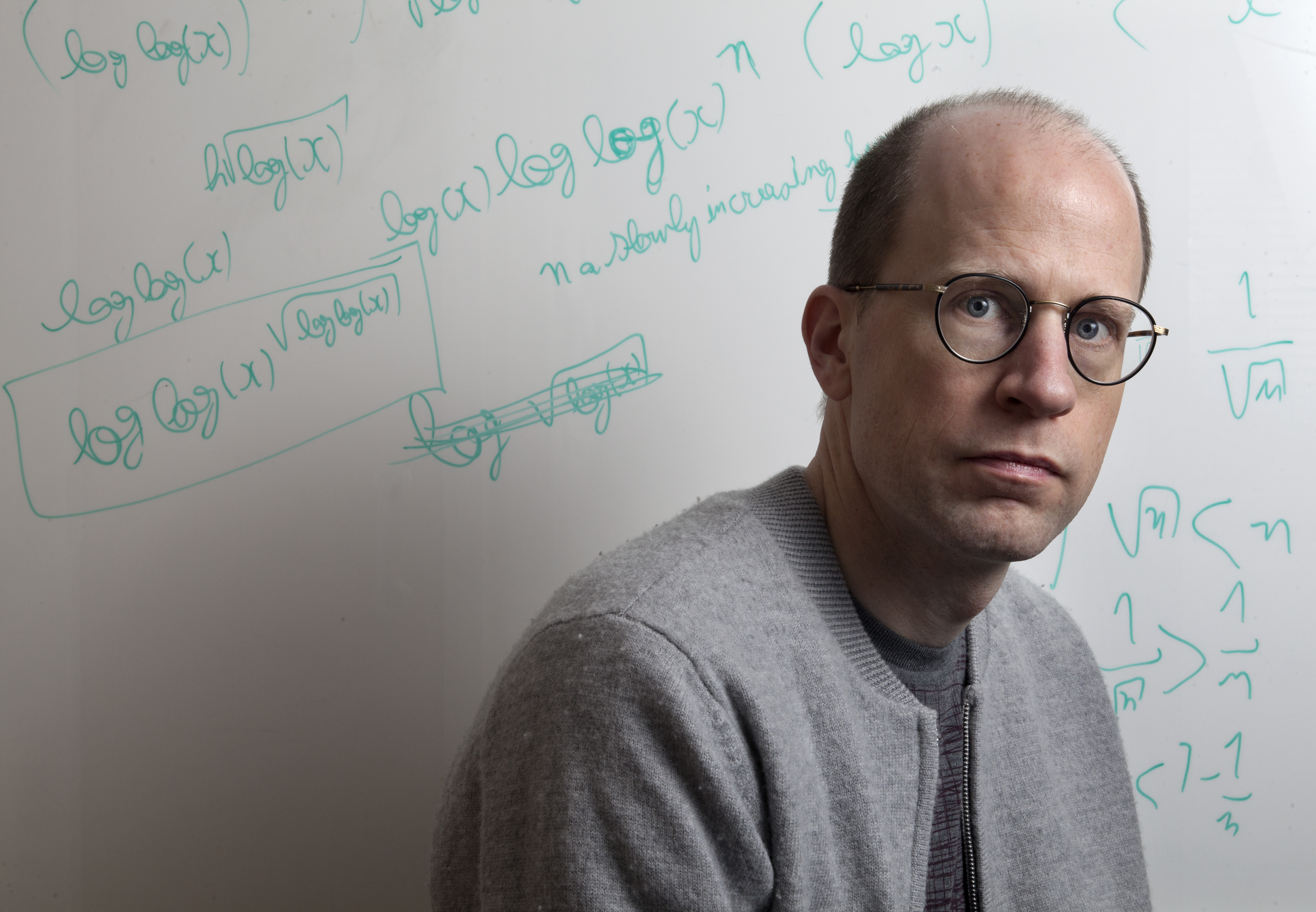

But philosopher Nick Bostrom highlighted that an ASI wouldn’t even have to be actively hostile to humans for various doomsday scenarios to play out. In a 2012 paper, he suggested that the intelligence of an entity is independent of its goals, so an ASI could have motivations that are completely alien to us and not aligned with human well-being.

Bostrom fleshed out this idea with a thought experiment in which a super-capable AI is set the seemingly innocuous task of producing as many paper-clips as possible. If unaligned with human values, it may decide to eliminate all humans to prevent them from switching it off, or so it can turn all the atoms in their bodies into more paperclips.

Rocktäschel is more optimistic. "We build current AI systems to be helpful, but also harmless and honest assistants by design," he said. "They are tuned to follow human instructions, and are trained on feedback to provide helpful, harmless, and honest answers."

While Rocktäschel admitted these safeguards can be circumvented, he's confident we will develop better approaches in the future. He also thinks that it will be possible to use AI to oversee other AI, even if they are stronger.

Hulme said most current approaches to "model alignment" — efforts to ensure that AI is aligned with human values and desires — are too crude. Typically, they either provide rules for how the model should behave or train it on examples of human behavior. But he thinks these guardrails, which are bolted on at the end of the training process, could be easily bypassed by ASI.

Instead, Hulme thinks we must build AI with a "moral instinct." His company Conscium is attempting to do that by evolving AI in virtual environments that have been engineered to reward behaviors like cooperation and altruism. Currently, they are working with very simple, "insect-level" AI, but if the approach can be scaled up, it could make alignment more robust. "Embedding morals in the instinct of an AI puts us in a much safer position than just having these sort of Whack-a-Mole guard rails," said Hulme.

Not everyone is convinced we need to start worrying quite yet, though. One common criticism of the concept of ASI, said Rocktäschel, is that we have no examples of humans who are highly capable across a wide range of tasks, so it may not be possible to achieve this in a single model either. Another objection is that the sheer computational resources required to achieve ASI may be prohibitive.

More practically, how we measure progress in AI may be misleading us about how close we are to superintelligence, said Alexander Ilic, head of the ETH AI Center at ETH Zurich, Switzerland. Most of the impressive results in AI in recent years have come from testing systems on several highly contrived tests of individual skills such as coding, reasoning or language comprehension, which the systems are explicitly trained to pass, said Ilic.

He compares this to cramming for exams at school. "You loaded up your brain to do it, then you wrote the test, and then you forgot all about it," he said. "You were smarter by attending the class, but the actual test itself is not a good proxy of the actual knowledge."

AI that is capable of passing many of these tests at superhuman levels may only be a few years away, said Ilic. But he believes today’s dominant approach will not lead to models that can carry out useful tasks in the physical world or collaborate effectively with humans, which will be crucial for them to have a broad impact in the real world.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.