New 'microcomb' chip brings us closer to super accurate, fingertip-sized atomic clocks

Breakthrough could pave the way for next-generation GPS in drones, smartphones and self-driving cars, scientists say.

A new comb-like computer chip could be the key to equipping drones, smartphones and autonomous vehicles with military-grade positioning technology that was previously confined to space agencies and research labs.

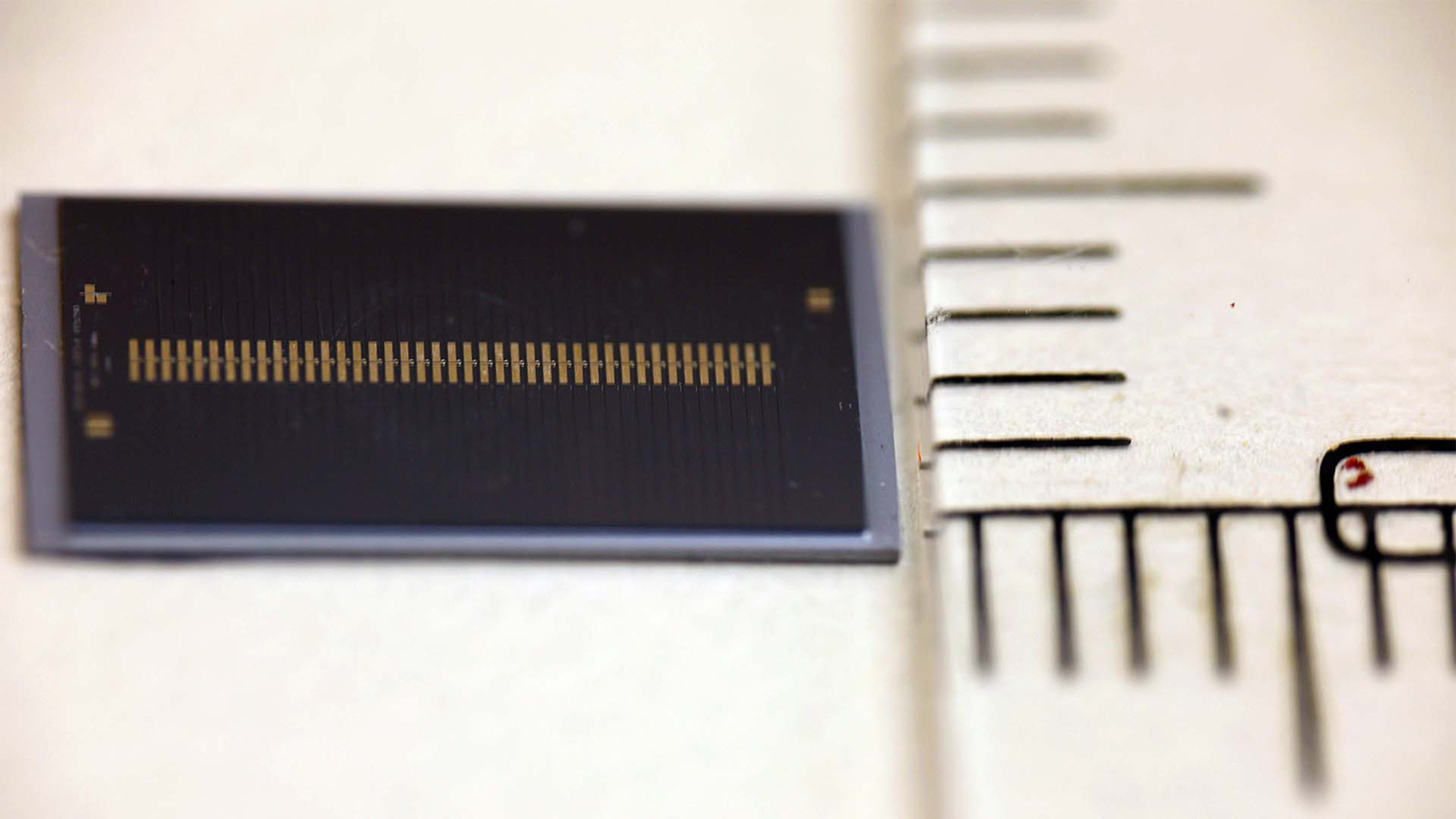

Scientists have developed a "microcomb chip" — a 5 millimeter (0.2 inches) wide computer chip equipped with tiny teeth like those on a comb — that could make optical atomic clocks, the most precise timekeeping pieces on the planet, small and practical enough for real-world use.

This could mean GPS-equipped systems a thousand times more accurate than the best we have today, improving everything from smartphone and drone navigation to seismic monitoring and geological surveys, the researchers said in a statement. They published their findings Feb. 19 in the journal Nature Photonics.

Up and atom

"Today's atomic clocks enable GPS systems with a positional accuracy of a few meters [where 1 meter is 3.3 feet]. With an optical atomic clock, you may achieve a precision of just a few centimeters [where 1 centimeter is 0.4 inches]," study co-author Minghao Qi, professor of electrical and computer engineering at Purdue University, said in the statement.

Related: How long is a second?

"This improves the autonomy of vehicles, and all electronic systems based on positioning. An optical atomic clock can also detect minimal changes in latitude on the Earth's surface and can be used for monitoring, for example, volcanic activity."

There are approximately 400 high-precision atomic clocks worldwide, which use the principles of quantum mechanics to keep time.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This typically involves using microwaves to stimulate atoms to shift between energy states. These shifts, called oscillations, happen naturally at an extremely high rate, acting like an ultra-precise ticking clock that keeps timekeeping accurate to within a billionth of a second.

That is why atomic clocks form the backbone of Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) — which is used to set global time zones — and GPS (global positioning system) satellites, which rely on atomic timekeeping to provide positioning data to cars, smartphones and other devices.

Despite this incredible accuracy, traditional atomic clocks are far less accurate than optical atomic clocks. Where standard atomic clocks use microwave frequencies to excite atoms, optical atomic clocks use laser light, enabling them to measure atomic vibrations at a much finer scale — making them thousands of times more precise.

Until now, optical atomic clocks have been confined to extremely limited scientific and research environments, such as NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). This is because they are extremely complex, putting them well out of reach of your standard Casio fan.

Tapping into the teeth of a comb

Microcomb chips could change this by bridging the gap between high-frequency optical signals (which optical atomic clocks use) and the radio frequencies used in the navigation and communication systems that modern electronics rely on.

"Like the teeth of a comb, a microcomb consists of a spectrum of evenly distributed light frequencies. Optical atomic clocks can be built by locking a microcomb tooth to a ultra-narrow-linewidth laser, which in turn locks to an atomic transition with extremely high frequency stability," the researchers explained in the statement.

They likened the new system to a set of gears, where a tiny, fast-spinning gear (the optical frequency) drives a larger, slower one (the radio frequency). Just as gears transfer motion while reducing speed, the microcomb acts as a converter that changes the ultra-fast oscillations of atoms into a stable time signal that electronics can process.

"Moreover, the minimal size of the microcomb makes it possible to shrink the atomic clock system significantly while maintaining its extraordinary precision," study co-author Victor Torres Company, professor of photonics at Chalmers, said in the statement. "We hope that future advances in materials and manufacturing techniques can further streamline the technology, bringing us closer to a world where ultra-precise timekeeping is a standard feature in our mobile phones and computers."

Owen Hughes is a freelance writer and editor specializing in data and digital technologies. Previously a senior editor at ZDNET, Owen has been writing about tech for more than a decade, during which time he has covered everything from AI, cybersecurity and supercomputers to programming languages and public sector IT. Owen is particularly interested in the intersection of technology, life and work – in his previous roles at ZDNET and TechRepublic, he wrote extensively about business leadership, digital transformation and the evolving dynamics of remote work.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.