AI-designed chips are so weird that 'humans cannot really understand them' — but they perform better than anything we've created

AI models have, within hours, created more efficient wireless chips through deep learning, but it is unclear how their 'randomly shaped' designs were produced.

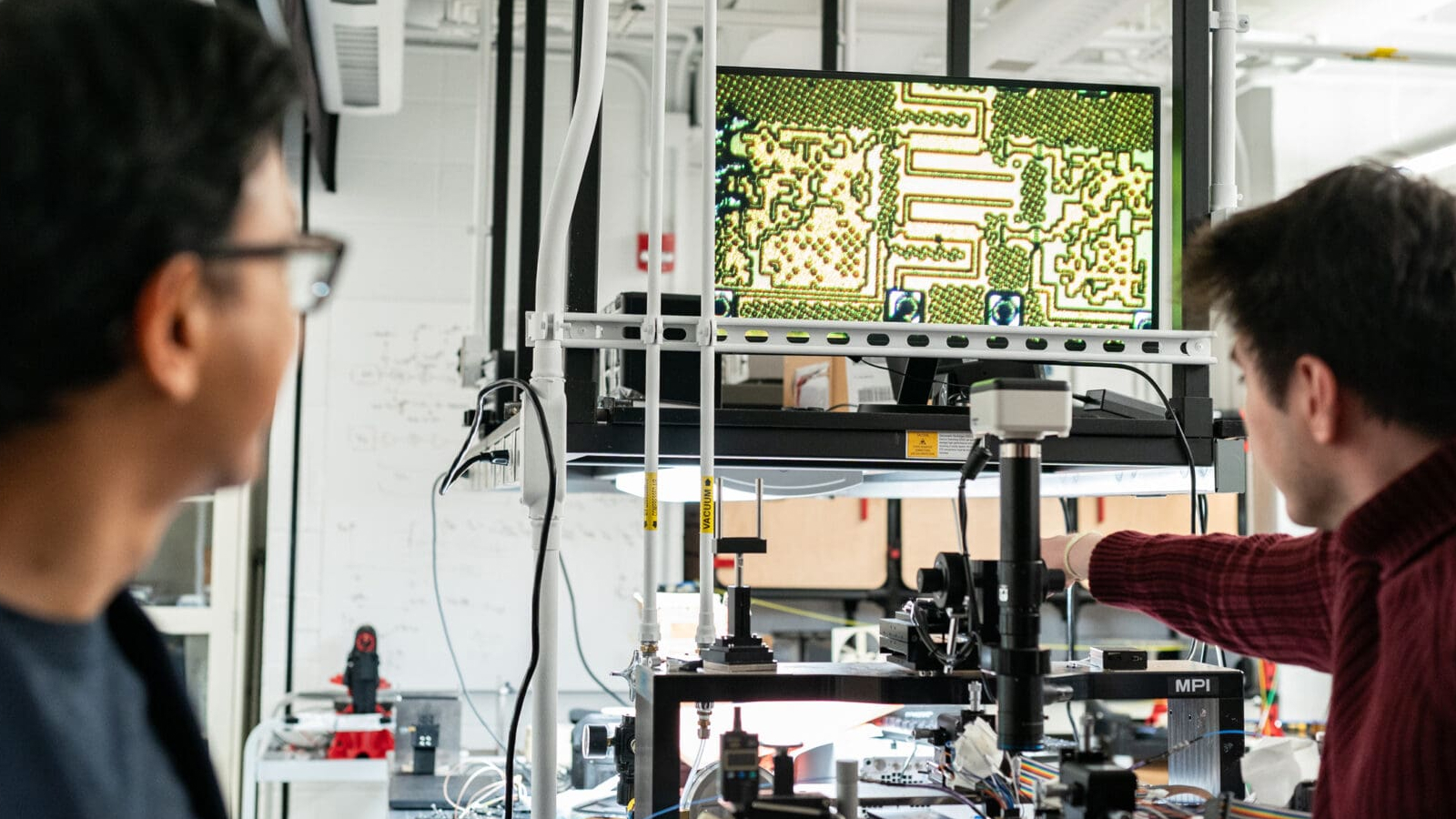

Engineering researchers have demonstrated that artificial intelligence (AI) can design complex wireless chips in hours, a feat that would have taken humans weeks to complete.

Not only did the chip designs prove more efficient, the AI took a radically different approach — one that a human circuit designer would have been highly unlikely to devise. The researchers outlined their findings in a study published Dec. 30 2024 in the journal Nature Communications.

The research focused on millimeter-wave (mm-Wave) wireless chips, which present some of the biggest challenges facing manufacturers due to their complexity and need for miniaturization. These chips are used in 5G modems, now commonly found in phones.

Manufacturers currently rely on a mix of human expertise, bespoke circuit designs and established templates. Each new design then goes through a slow process of optimization, based on trial and error because it is often so complex that a human cannot fully understand what is happening inside the chip. This leads to a cautious, iterative approach based on what has worked before.

Related: 6G speeds hit 100 Gbps in new test — 500 times faster than average 5G cellphones

In this case, however, researchers at Princeton Engineering and the Indian Institute of Technology posited that deep-learning-based AI models could use an inverse design method — one that specifies the desired output and leaves the algorithm to determine the inputs and parameters.

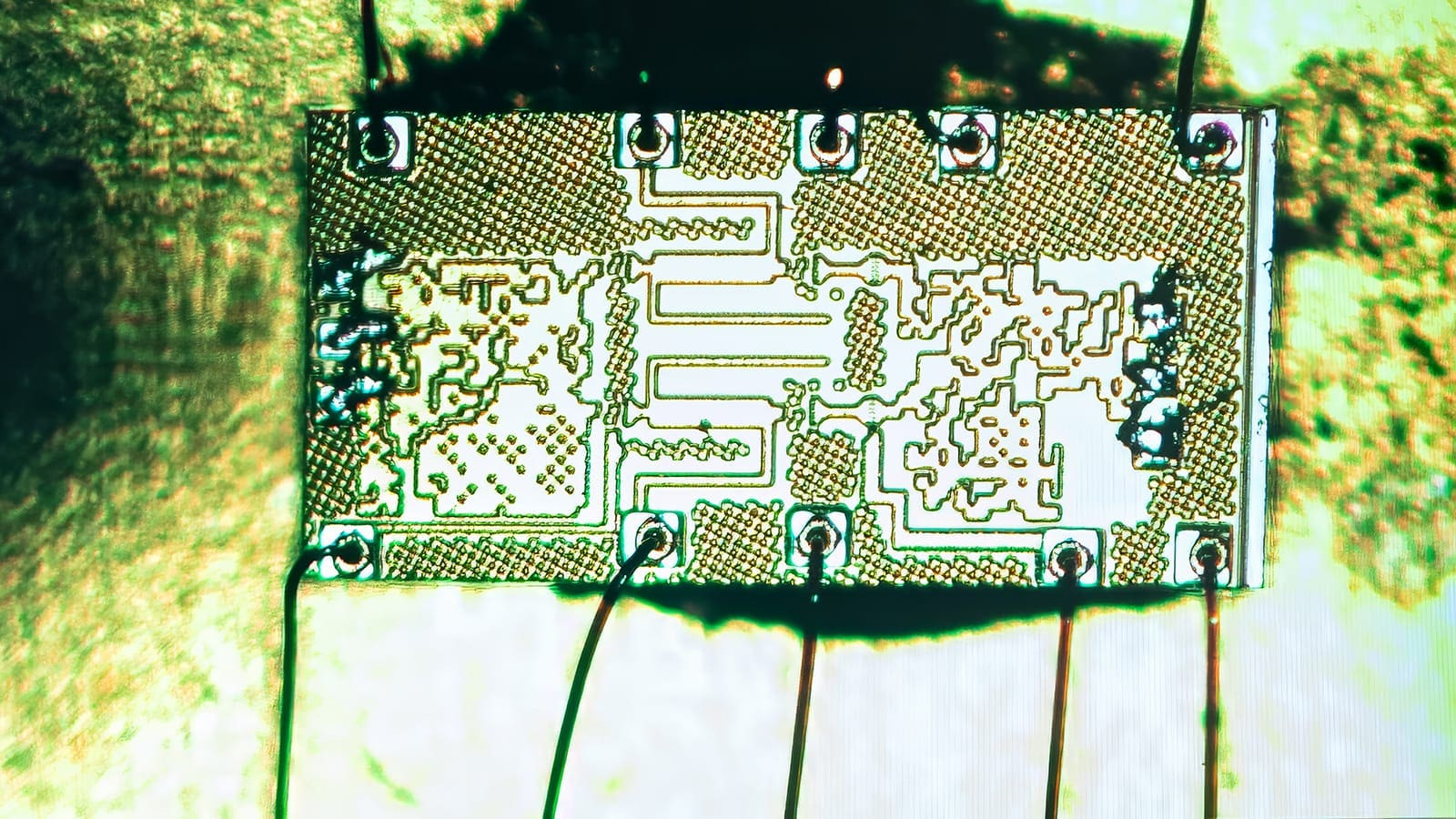

The AI also considers each chip as a single artifact, rather than a collection of existing elements that need to be combined. This means that established chip design templates, the ones that no one understands but probably hide inefficiencies, are cast aside.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The future of chip design?

In this experiment, the resulting structures "look randomly shaped," said lead author Kaushik Sengupta, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at Princeton. "Humans cannot really understand them."

And when Sengupta’steam manufactured the chips, they found the AI creations hit performance levels beyond those of existing designs.

Although the findings suggest that the design of such complex chips could be handed over to AI, Sengputa was keen to point out that pitfalls remain “that still require human designers to correct.” In particular, many of the designs produced by the algorithm did not work– equivalent to the "hallucinations" produced by current generative AI tools.

"The point is not to replace human designers with tools," said Sengputa. "The point is to enhance productivity with new tools."

The speed with which iterative designs can be developed opens up new possibilities, too. Some chip designs can be geared towards energy efficiency, others to outright performance or to extending the frequency range.

Wireless chips are of growing importance, with an ever-growing demand for miniaturization, so this research is a valuable step forward. But Sengupta said that if his team’s method can be extended to other parts of a circuit’s design, it could change the way we design electronics in the future. "This is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of what the future holds for the field."

Tim Danton is a journalist and editor who has been covering technology and innovation since 1999. He is currently the editor-in-chief of PC Pro, one of the U.K.'s leading technology magazines, and is the author of a computing history book called The Computers That Made Britain. He is currently working on a follow-up book that covers the very earliest computers, including The ENIAC. His work has also appeared in The Guardian, Which? and The Sunday Times. He lives in Buckinghamshire, U.K.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.