Scientists create ultra-efficient magnetic 'universal memory' that consumes much less energy than previous prototypes

MRAM can be energy-intensive, but a new generation of this technology will enable greater computing power and resilience, as well as much lower energy requirements.

Scientists in Japan have developed a new kind of "universal" computing memory that is much faster and less energy-hungry than modules used in the best laptops and PCs today.

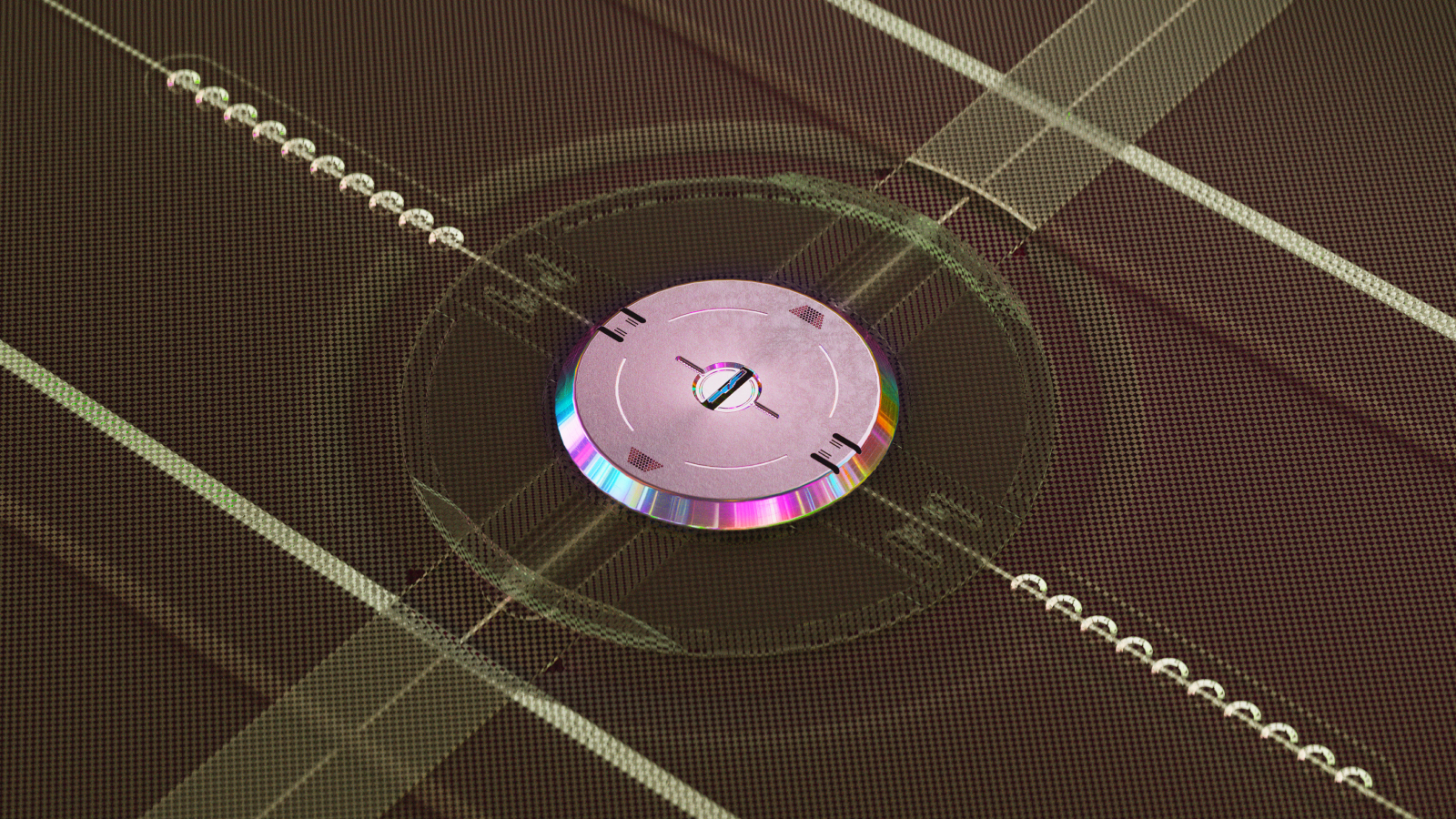

Magnetoresistive Random Access Memory (MRAM) is a type of universal memory device that can overcome some of the limitations of conventional RAM, which can slow down at peak demand due to a relatively low capacity. Universal memory is a storage format that combines the speed of existing RAM and the ability of storage to retain information without a power supply

Universal memory like MRAM is a better proposition than the components used in computers and smart devices today as it offers higher speeds and much greater capacity, as well as better endurance.

This new technology operates at faster speeds and with greater capacity than conventional RAM, but overcomes the problem of high power requirements for data writing — which has previously been a challenge for MRAM.

MRAM devices consume little power in their standby state but need a large electric current to switch the direction of magnetization vector configurations of magnetic tunnel junctions, thereby using the direction of magnetization to represent the binary values in computers. That makes it infeasible for use in most computing systems and to achieve low-power data writing, a more efficient method for switching these vectors was needed.

Related: 'Quantum memory breakthrough' may lead to a quantum internet

In a paper published Dec. 25 2024 in the journal Advanced Science, researchers reported developing a new component for controlling the electric field in MRAM devices. Their method requires far less energy to switch polarity, thereby lowering the power requirements and improving the speed at which processes are performed.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Next-generation computing memory

The prototype component they built was called a "multiferroic heterostructure" — a ferromagnetic material and piezoelectric material, but with an ultrathin vanadium between them — that can be magnetized by an electric field. This differs from other MRAM devices, which did not have the vanadium layer.

Structural fluctuations in the ferromagnetic layer meant that it was difficult for a stable direction of magnetization to be maintained in previous MRAM devices. In order to overcome this stability issue, the Vanadium wafer between the ferromagnetic and piezoelectric layers acts as a buffer between the two.

By passing an electric current through the materials, the scientists demonstrated that the magnetic state could switch direction. The materials could maintain their shape and form, which previous versions could not do. Furthermore, the magnetic state was maintained after the electric charge was no longer present, allowing a stable binary state to be maintained without power.

The study did not cover the degradation in the switching efficiency over time. This tends to be a common problem with a wide range of electrical devices. For example, a common complaint with rechargeable household batteries is that they can only be charged a certain number of times (approximately 500) before their capacity degrades.

Ultimately, the new MRAM technology could enable more powerful commercial computing while also offering a longer use life, the scientists said. That's because the new switching technique requires far less power than previous solutions, has a greater resilience than current RAM technologies and does not require moving parts.

Peter is a degree-qualified engineer and experienced freelance journalist, specializing in science, technology and culture. He writes for a variety of publications, including the BBC, Computer Weekly, IT Pro, the Guardian and the Independent. He has worked as a technology journalist for over ten years. Peter has a degree in computer-aided engineering from Sheffield Hallam University. He has worked in both the engineering and architecture sectors, with various companies, including Rolls-Royce and Arup.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.