Future robots could one day tell how you're feeling by measuring your sweat, scientists say

Scientists say a phenomenon called "skin conductance," which changes when you sweat, is a surprisingly accurate method for detecting emotions — with future robots that detect this able to tell your emotions.

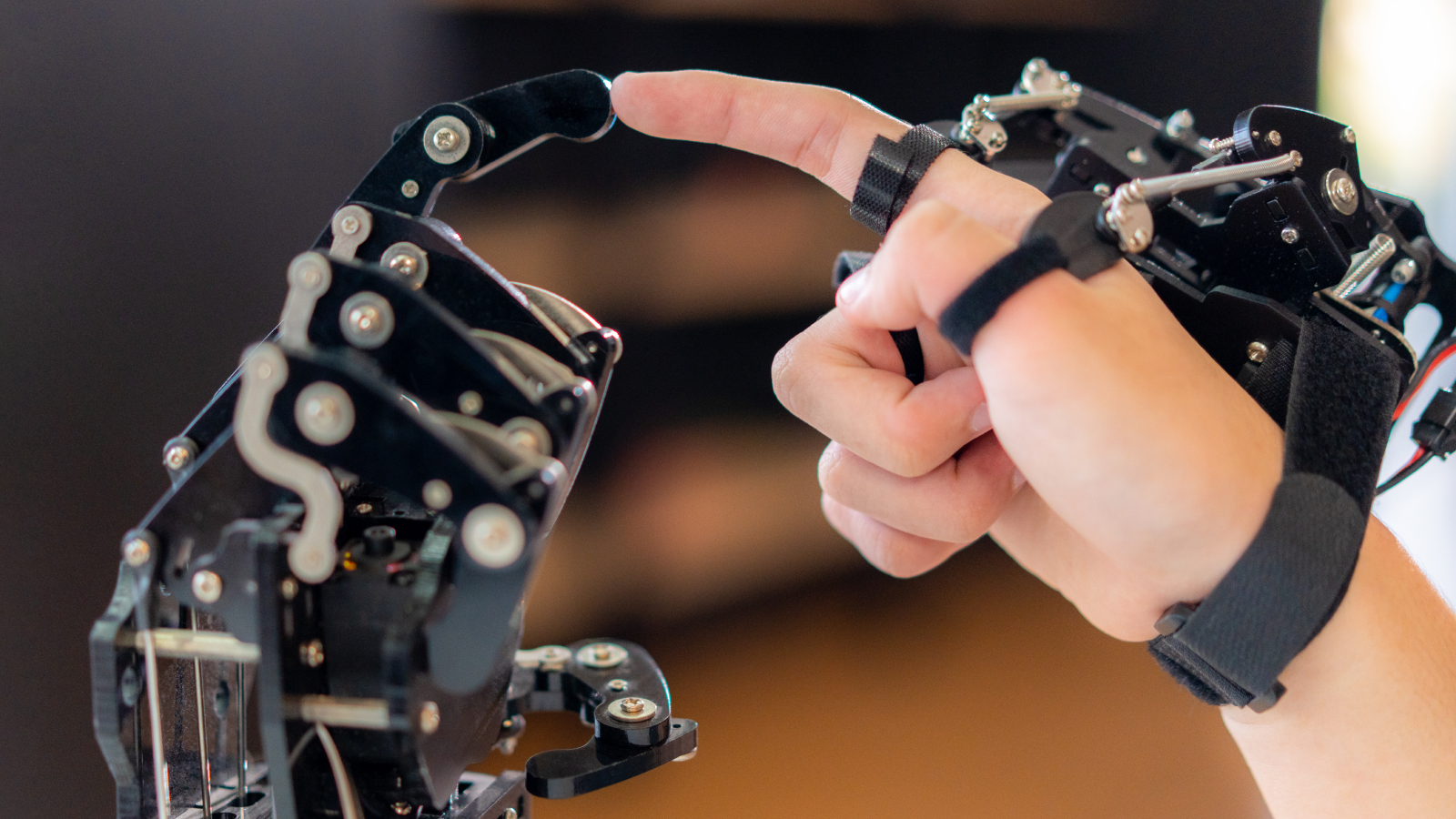

Future robots might be able to detect how you're feeling just by touching your skin.

In a new study, scientists used skin conductance — a measure of how well skin conducts electricity — to assess the emotions of 33 participants who were shown emotionally evocative videos.

Because skin conductance changes when you sweat, they found a correlation between these measurements and videos that elicited feelings of fear, surprise and "family bonding emotions," making skin conductance an accurate method for detecting changes in emotion in real time.

When used in conjunction with other physiological signals, like heart rate monitoring and brain activity, skin conductance could play a central role in the development of emotionally intelligent devices and services, the scientists explained in a paper published Oct. 15 in the journal IEEE Access.

"To date, few studies have examined how the dynamics of skin conductance responses differ among emotions, despite high responsiveness being a key feature of skin conductance," the scientists said in the study. "The results of this study are expected to contribute to the development of technologies that can be used to accurately estimate emotions, when combined with other physiological signals."

Although the study didn't specifically explore integrating the technology with robotics, systems that can respond to human emotions hold several promising applications. These could, hypothetically, include smart devices that play soothing music when you are stressed or streaming platforms that tailor content recommendations to your mood.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To be effective, though, these devices must detect and interpret emotions accurately. In the paper, the scientists noted that typical emotion-detection technologies rely on facial recognition and speech analysis. These technologies not only tend to be unreliable — particularly when video and audio signals aren't clear — but also carry inherent privacy concerns, the team said.

Skin conductance may offer a solution, according to the study. When humans experience an emotional reaction, their sweat glands activate, which changes their skin's electrical properties. These changes occur within one to three seconds, providing very quick feedback on a person's emotional state.

For the study, scientists at Tokyo Metropolitan University attached probes to the fingers of 33 participants and showed them a variety of emotionally charged clips, including horror movie scenes, comedy sketches and family reunion videos. As they watched, the team measured how quickly participants' skin conductance peaked and how long it took to return to normal.

The study revealed distinct patterns for different emotions. Fear responses lasted the longest, which the scientists explained was likely an evolutionary trait that keeps humans alert to danger. Family bonding emotions, described as a mix of happiness and sadness, caused slower responses, which they said could have been because the two feelings interfered with each other.

Humor triggered the fastest reactions, but they faded quickly, the study showed. The reason for this wasn't immediately clear, but the scientists noted that "literature on the dynamics of skin conductance caused by funniness and fear" is fairly scant.

Although the method isn't perfect, combining skin conductance with other physiological signals — like heart rate, electromyography and brain activity — could improve the accuracy of the technique, the researchers said.

"There is a growing demand for techniques to estimate individuals' subjective experiences based on their physiological signals to provide them with emotionally evocative services," the scientists wrote in the study. "Therefore, further exploration of these physiological signals in this study, particularly skin conductance responses, can advance techniques for emotion recognition."

Owen Hughes is a freelance writer and editor specializing in data and digital technologies. Previously a senior editor at ZDNET, Owen has been writing about tech for more than a decade, during which time he has covered everything from AI, cybersecurity and supercomputers to programming languages and public sector IT. Owen is particularly interested in the intersection of technology, life and work – in his previous roles at ZDNET and TechRepublic, he wrote extensively about business leadership, digital transformation and the evolving dynamics of remote work.