Cretaceous 'terror crocodile' crushed dinosaurs with banana-size teeth

This enormous predator had jaws powerful enough to subdue massive dinosaur prey.

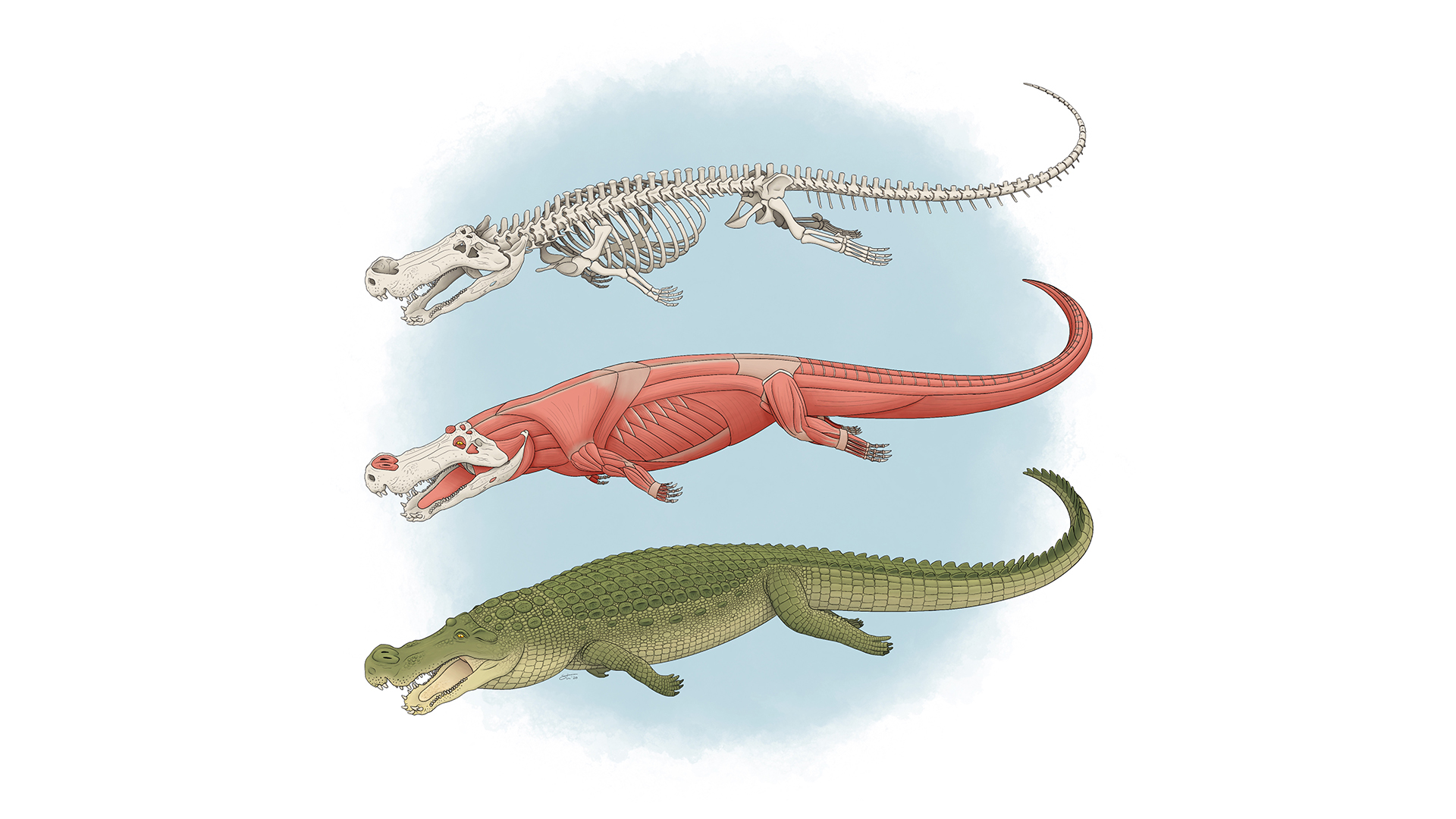

An enormous Cretaceous crocodile relative hunted dinosaurs, ripping them apart using powerful jaws lined with teeth "the size of bananas," researchers say.

Known as Deinosuchus, which means "terrible crocodile" in Greek, this lineage of semiaquatic reptiles certainly lived up to its name. They were among the biggest predators in their watery North American habitats, where they lived between 75 million and 82 million years ago. And with bodies at least 33 feet (10 meters) long, they could subdue just about any animal that wandered within reach — including dinosaurs.

Paleontologists had previously identified three species of the terror crocs. But some experts argued that fossil evidence defining the species was incomplete, and that the three species could just be one that ranged across the continent. Scientists recently re-evaluated fossils of so-called terror crocodiles, combining existing species and describing a new one, Deinosuchus schwimmeri, in a new study.

Related: Crocs & dinos: See images of 25 amazing ancient beasts

In addition to having banana-size teeth, the newly described D. schwimmeri was "a bizarre, monstrous predator," said lead study author Adam Cossette, an assistant professor in the New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine at Arkansas State University. Cossette and his colleagues described the new species by sampling fossils from across North America, and by evaluating new terror croc fossils from western Texas, according to the study.

"Until now, the complete animal was unknown," Cossette said in a statement. The species name honors paleontologist David Schwimmer, a professor at Columbus State University in Georgia (not to be confused with the actor David Schwimmer, who played a paleontologist from the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, in the TV show "Friends").

Deinosuchus are crocodylians — the group that includes modern alligators, crocodiles and gharials — and despite the name "terrible crocodile," the Deinosuchus lineage was more closely related to alligators, the researchers determined. They also found that the species D. rugosus was likely misidentified. D. rugosus fossils (of which there are very few) likely came from two other species — D. riograndensis or D. schwimmeri — both of which were described later but boasted more complete sets of fossils.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The species status of the terror croc D. hatcheri, also based on scant and fragmented fossil evidence, is also questionable, the authors reported.

D. schwimmeri inhabited North America's eastern shores and the coastal Atlantic, while D. riograndensis and D. hatcheri lived in the West; at the time, the Western Interior Seaway geographically separated the eastern and western species, the study authors wrote.

But no matter the species, "Deinosuchus was a giant that must have terrorized dinosaurs that came to the water's edge to drink," Cossette said.

While Deinosuchus shared many features with its crocodylian relatives, a couple of peculiarities set them apart. Their broad, elongated heads ended in a bulbous snout — a shape that is unique among this group of reptiles, according to the study. At the end of the snout are two large vents, which are also unique to Deinosuchus.

Scientists have yet to uncover the function of the apertures and snout shape, though they may be linked to thermoregulation, and may have helped the terror crocs keep cool, according to the study.

"It was a strange animal," said study co-author Christopher Brochu, a paleontologist and professor in the department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Iowa. The findings were published online Aug. 10 in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.