Thousands of new viruses discovered in the ocean

More than 5,000 new RNA virus species were identified.

More than 5,000 new virus species have been identified in the world's oceans, according to a new study.

The study researchers analyzed tens of thousands of water samples from around the globe, hunting for RNA viruses, or viruses that use RNA as their genetic material. The novel coronavirus, for instance, is a type of RNA virus. These viruses are understudied compared with DNA viruses, which use DNA as their genetic material, the authors said.

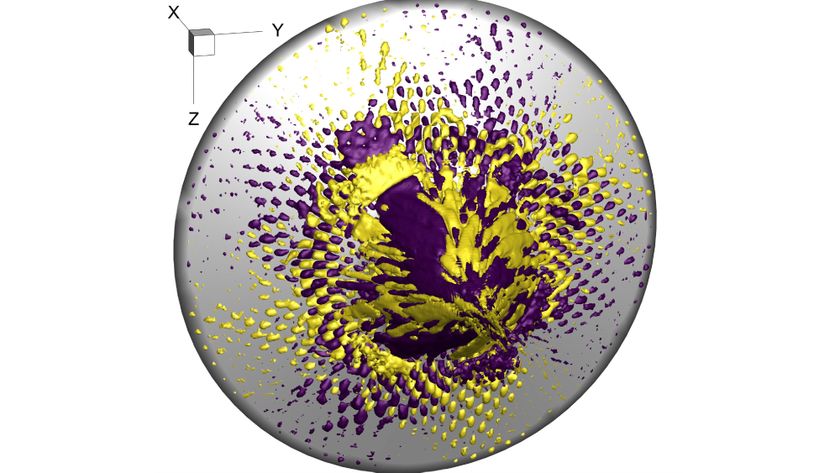

The diversity of the newfound viruses was so great that the researchers have proposed doubling the number of taxonomic groups needed to classify RNA viruses, from the existing five phyla to 10 phyla. (Phylum is a broad classification in biology just below "kingdom.")

"There's so much new diversity here – and an entire [new] phylum, the Taraviricota, were found all over the oceans, which suggests they’re ecologically important," study lead author Matthew Sullivan, a professor of microbiology at The Ohio State University, said in a statement.

Related: The deadliest viruses in history

Studies of RNA viruses have usually focused on those that cause diseases, according to Sullivan. (Some well-known RNA viruses include influenza, Ebola and the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.) But these are just a "tiny slice" of RNA viruses on Earth, Sullivan said.

"We wanted to systematically study them on a very big scale and explore an environment no one had looked at deeply," Sullivan said in the statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For the study, published Thursday (April 7) in the journal Science, the researchers analyzed 35,000 water samples taken from 121 locations in all five of the world's oceans. The researchers are part of the Tara Oceans Consortium, a global project to study the impact of climate change on the ocean.

They examined genetic sequences extracted from small aquatic organisms known as plankton, which are common hosts for RNA viruses, the researchers said. They homed in on sequences belonging to RNA viruses by looking for an ancient gene called RdRp, which is found in all RNA viruses but is absent from other viruses and cells. They identified over 44,000 sequences with this gene.

But the RdRp gene is billions of years old, and it has evolved many times. Because the gene's evolution goes so far back, it was difficult for the researchers to determine the evolutionary relationship between the sequences. So the researchers used machine learning to help organize them.

Overall, they identified about 5,500 new RNA virus species that fell into the five existing phyla, as well as the five newly proposed phyla, which the researchers named Taraviricota, Pomiviricota, Paraxenoviricota, Wamoviricota and Arctiviricota.

Virus species in the Taraviricota phylum were particularly abundant in temperate and tropical waters, while viruses in the Arctiviricota phylum are abundant in the Arctic Ocean, the researchers wrote in The Conversation.

Understanding how the RdRp gene diverged over time could lead to a better understanding of how early life evolved on Earth, the authors said.

"RdRp is supposed to be one of the most ancient genes — it existed before there was a need for DNA," study co-first author Ahmed Zayed, a research scientist in microbiology at Ohio State, said in the statement. "So we’re not just tracing the origins of viruses, but also tracing the origins of life."

Originally published on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.