An aurora that lit up the sky over the Titanic might explain why it sank

"The northern lights were very strong that night," a witness recalled.

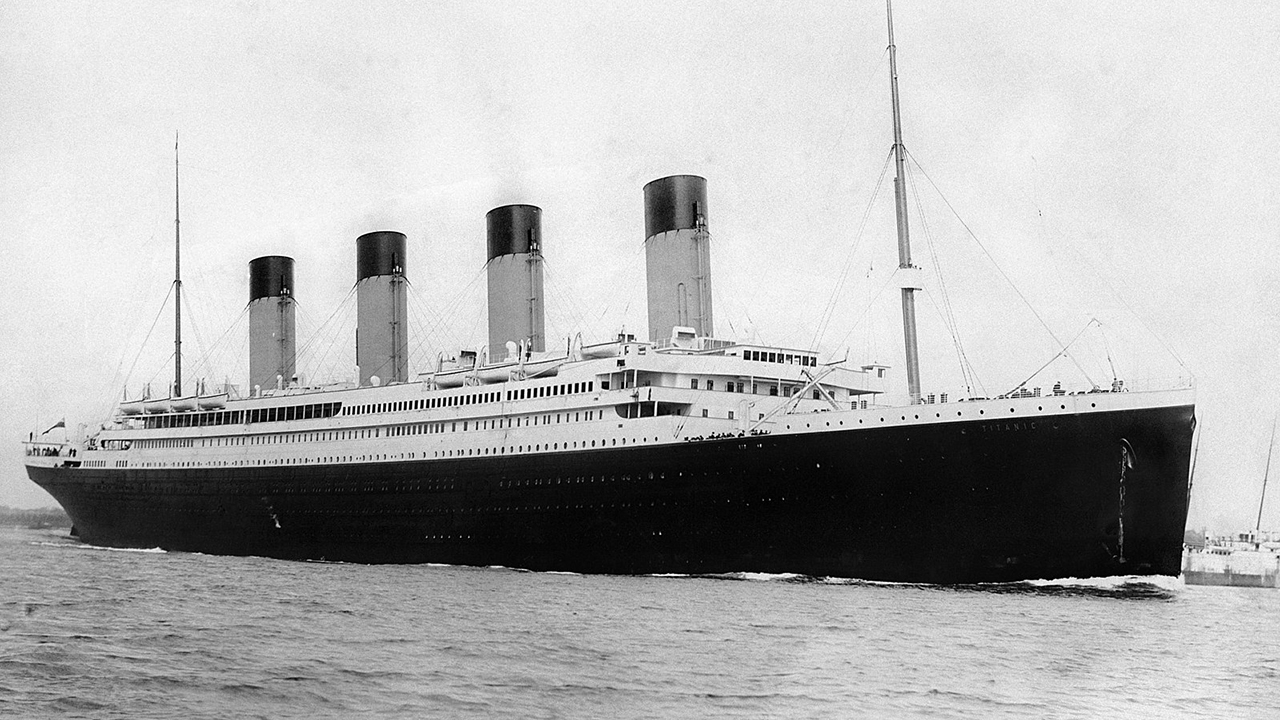

Glowing auroras shimmered in skies over the northern Atlantic Ocean on April 15, 1912 — the night the RMS Titanic sank. Now, new research hints that the geomagnetic storm behind the northern lights could have disrupted the ship's navigation and communication systems and hindered rescue efforts, fueling the disaster that killed more than 1,500 passengers.

Eyewitnesses described aurora glows in the region as the Titanic went down, with one observer testifying that "the northern lights were very strong that night," Mila Zinkova, an independent weather researcher and photographer, reported in a new study, published online Aug. 4 in the journal Weather.

Related: In Photos: Stunning shots of the Titanic shipwreck

Auroras form from solar storms, when the sun expels high-speed streams of electrified gas that hurtle toward Earth. As the charged particles and energy collide with Earth's atmosphere, some travel down magnetic field lines to interact with atmospheric gases, glowing green, red, purple and blue, NASA says. These charged particles can also interfere with electrical and magnetic signals, causing surges and oscillations, according to NASA.

A solar storm (also called a geomagnetic storm) powerful enough to produce an aurora may also have affected compasses and wireless communication on the Titanic, and on nearby ships trying to come to her aid. Even a small disruption might have been enough to doom the vessel, Zinkova said in the study.

And the northern lights were highly visible when the Titanic sank. James Bisset, second officer of the RMS Carpathia (the ship that would rescue Titanic survivors) wrote in his log on the night of April 14, 1912: "There was no moon, but the Aurora Borealis glimmered like moonbeams shooting up from the northern horizon." In an entry made five hours later, Bisset noted that he could still see "greenish beams" of the aurora as the Carpathia neared the Titanic's lifeboats, Zinkova reported.

Survivors also described spotting the northern lights from their lifeboats at around 3 a.m. local time. The glow "arched fanwise across the northern sky, with faint streamers reaching towards the Pole-star," Titanic survivor Lawrence Beesley wrote.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

At the same time that the solar storm's charged particles were generating a pretty light show, they could also have been tugging at the Titanic's compass. A deviation of only 0.5 degrees would have been enough to steer the ship away from safety and place it on its fatal collision course toward an iceberg, Zinkova said in the study.

"This apparently insignificant error could have made the difference between colliding with the iceberg and avoiding it," she wrote.

"Freaky" signals

Radio signals that night were also "freaky," operators on the ocean liner RMS Baltic reported (the Baltic was one of the ships that responded to the Titanic's distress call, but the RMS Carpathia got there first, according to the Armstrong Browning Library at Baylor University in Waco, Texas). SOS signals sent by the Titanic to nearby ships went unheard, and responses to the Titanic were never received, according to Zinkova.

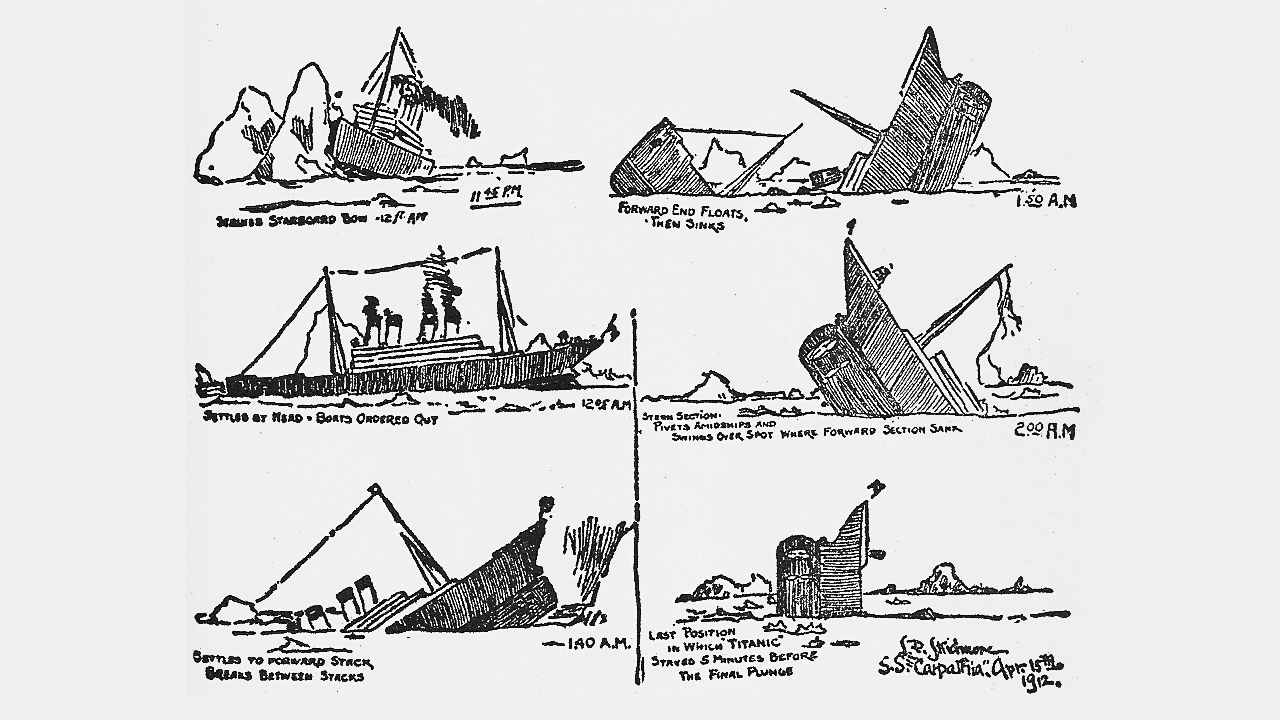

Related: Infographic: Why and how the Titanic sank

"The official report of the Titanic sinking suggested amateur radio enthusiasts had caused interference, by jamming the airwaves, and so prevented the accurate dissemination of emergency signals to other ships in the vicinity," she wrote.

"However, at the time they had incomplete knowledge of the influence that geomagnetic storms may have on the ionosphere and disruption to communication. It is proposed here that the ongoing moderate to strong geomagnetic storm near the aurora had a negative impact upon the receipt of accurate SOS signals by nearby vessels, as well as interference from amateur radio operators."

If geomagnetic disruption from a solar storm did take place, "it could have affected all aspects of the tragedy," including the navigation errors that caused the iceberg collision, and the failed SOS communications that delayed the arrival of rescue ships, Zinkova wrote.

Though the Titanic sank more than 100 years ago, the tale of that fateful voyage and its tragic conclusion continues to intrigue and fascinate. Objects recovered from that fateful day command hefty price tags at auction, such as a first-class lunch menu from April 14 that sold for $88,000 in 2015, and the battery-illuminated "flashlight cane" of a passenger and survivor that sold for $62,500 in 2019.

But while the ship's fame is undimmed, the wreck itself is rapidly disintegrating. When a team of explorers visited the Titanic in August of 2019, the first divers to do so in 14 years, they found that part of the ship's starboard side — where many of the state rooms were located — had been eroded by powerful ocean currents, metal-destroying microbes and corrosive salt, Live Science previously reported.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.