Ancient saber-toothed 'gorgons' bit each other in ritualized combat

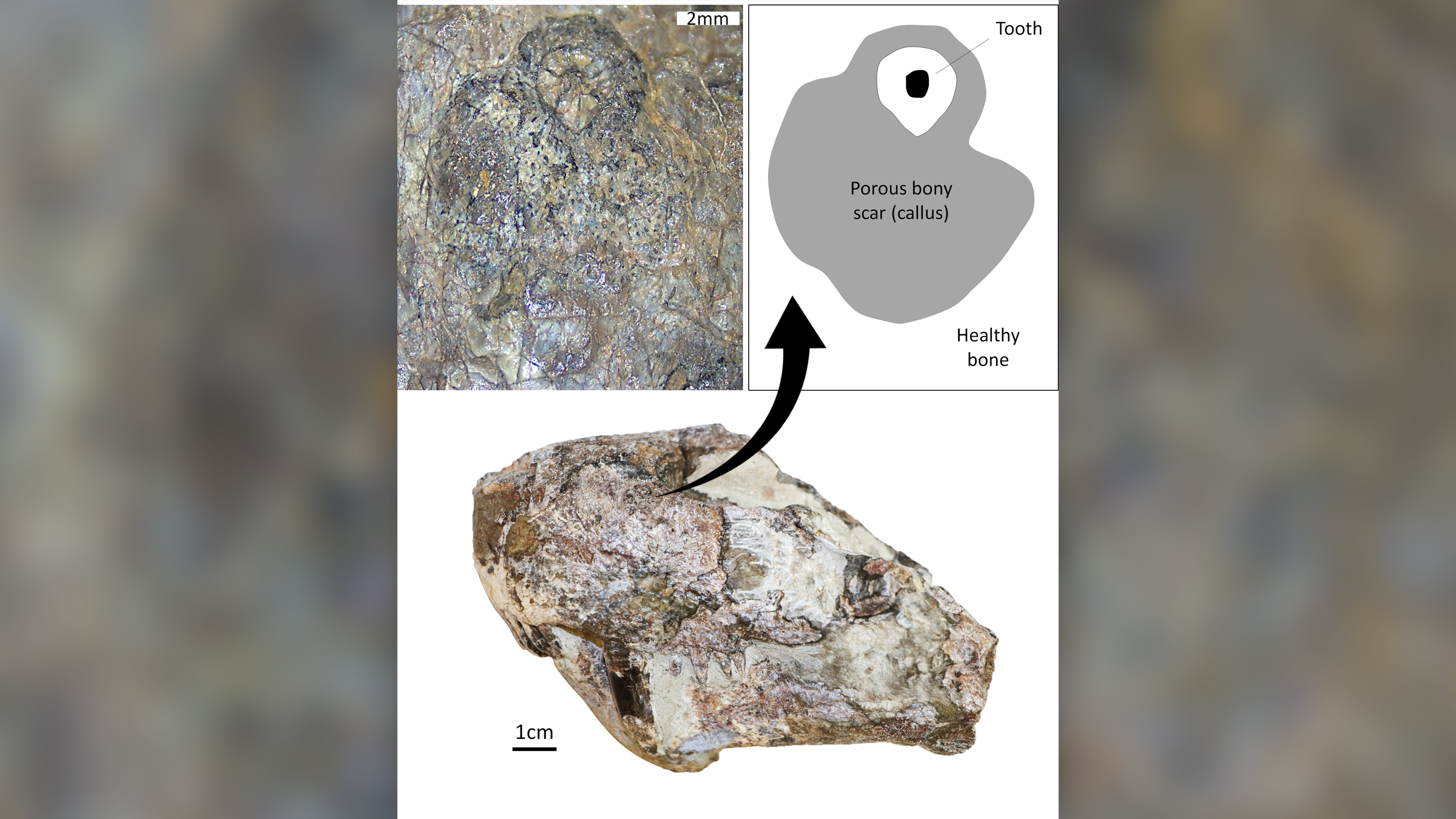

A broken tooth is still embedded in the "gorgon's" skull.

Long before dinosaurs walked the Earth, saber-toothed "gorgons" savagely bit each other on the face, a new study finds.

Fights between these animals — known as gorgonopsians, the dominant carnivores of the late Permian period (299 million to 251 million years ago) — were likely the result of competition between individuals vying for benefits, such as social dominance, desirable mates or territory. And they were probably not meant to be fatal, the study finds. Researchers made the discovery after analyzing a healed bite mark on a gorgonopsian skull discovered near Cape Town, South Africa.

The bite mark on the creature's snout still has a tooth embedded in it, making it the first ancient wound of its kind found in a gorgonopsian, a creature named after the mythical Greek gorgon, the researchers said.

"If we are right saying that this bite is the result of ritualized face-biting between two gorgonopsians of the same species," then this is the first evidence of social biting behavior in a non-mammalian synapsid," the group that gave rise to the mammals, said study lead researcher Julien Benoit, a senior researcher of paleontology at the Evolutionary Studies Institute of the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg.

Related: My, what sharp teeth! 12 living and extinct saber-toothed animals

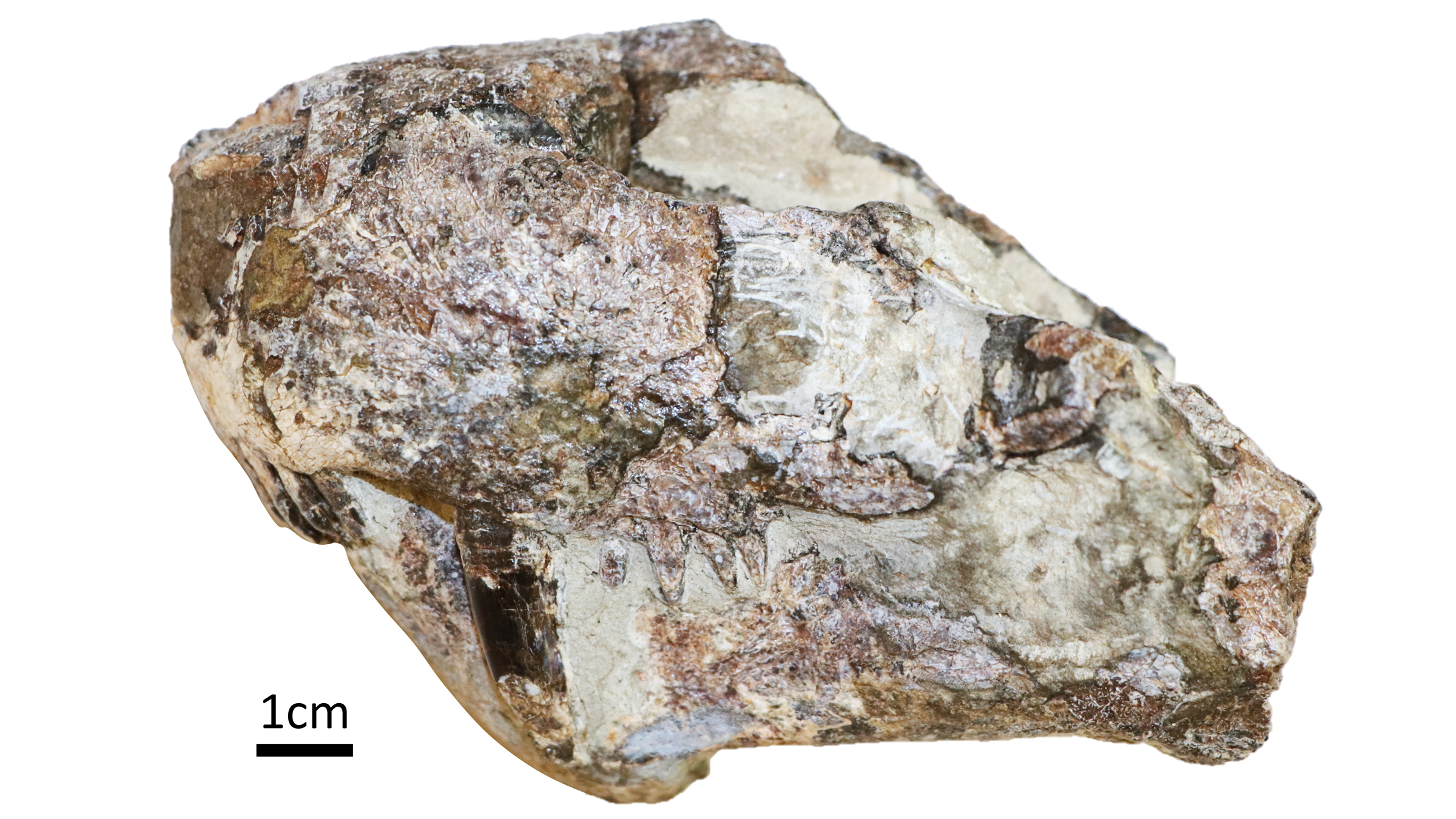

South African paleontologist Lieuwe Dirk Boonstra discovered the gorgonopsian skull and lower jaw in South Africa's semi-arid desert, the Karoo, in 1940, but its genus, possibly Arctognathus, remains unclear.

Despite the skull's long history, researchers didn't notice the bite mark until this year. They found the skull had healed after the vicious bite, so the gorgonopsian didn't immediately die from its injury. In fact, the "gorgon" likely lived for another two to nine weeks, based on mammalian healing rates, and the absence of a drainage channel for pus or other traces of infection suggest that the bite was not the ultimate cause of the gorgonopsian's death, the researchers wrote in the study.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Though gorgonopsians, which ranged from cat- to hippo-size, eventually came to rule their ecosystems in the late Permian, "the specimen we used for this study does not come from the late Permian, but the middle Permian, a time before gorgonopsians became the dominant predators," Benoit said. During that time, the fierce anteosaurs stalked Earth, so "our specimen was thus a relatively large carnivore in a world of gigantic monsters."

So, what left a broken tooth stuck in the gorgonopsian's skull? Or, as Benoit puts it, "Who would dare attack a gorgonopsian?"

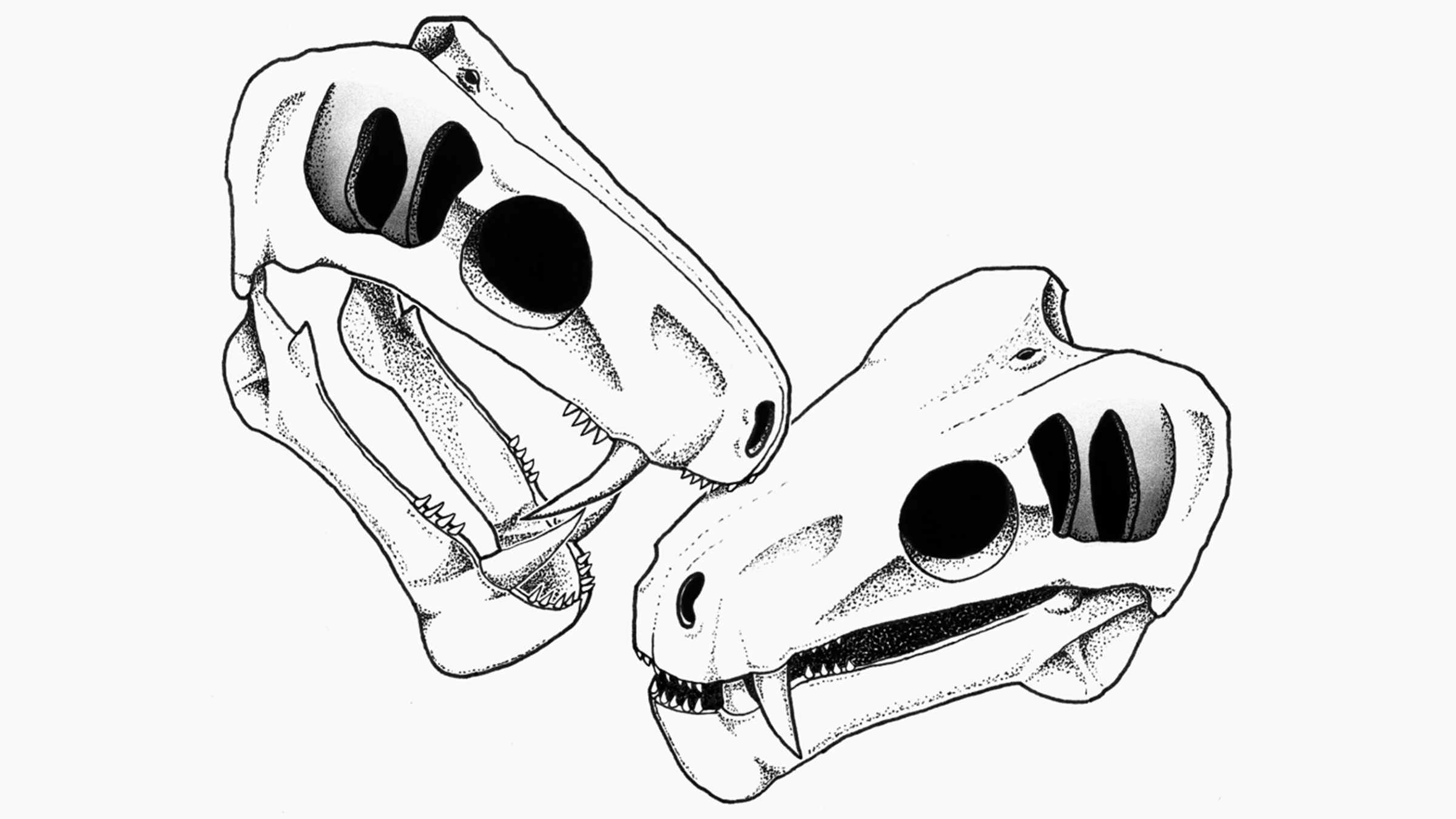

It's possible an anteosaur attacked it, but anteosaurs had large teeth and could likely easily "crush the skull of a gorgonopsian and obliterate it completely," he said. "This leaves us with the hypothesis that the bite was made by another gorgonopsian, not to kill it, but to assert dominance during ritualized combat."

Nowadays, adult reptiles and mammals, especially carnivores, use social biting to assert dominance, stimulate copulation and ovulation, compete for mates, territory and breeding rights, the researchers wrote in the study.

"Unlike a predatory bite that is meant to kill, non-lethal face biting is a common outcome of these kinds of ritualized combat," Benoit said. "To us, this strongly suggests that the biter was another gorognopsian of the same species, which is consistent with the size of the tooth."

Gorgonopsians were the first saber-toothed predators on record, arising hundreds of millions of years before the first saber-toothed cats prowled around. The broken tooth embedded in the skull wasn't a saber tooth, but probably a lateral incisor, a canine or a postcanine tooth, the researchers wrote in the study.

The discovery shows that complex behaviors between the species, such as biting behaviors, are "not unique to mammals and dinosaurs, but were more generalized and are older than previously thought," Benoit said. Previously, research showed that T. rex juveniles likely bit each other in the face, too.

The new research was published online June 21 in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution and presented online Nov. 4 at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology's annual conference.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.